In Iceland, as part of an international movement that began in Italy in 1986, Slow Food is taking a significant stance against the global dominance of fast food chains and mass-produced meals. This initiative, which started as a protest by Carlo Petrini against a McDonald’s near Rome’s Spanish Steps, has blossomed into a worldwide grassroots movement, officially launched in 1989 in Paris.

With over 100,000 members across more than 150 countries, Slow Food advocates for a deeper connection to our food sources, methods of production, and their impact on our health and the environment. Beyond mere enjoyment, Slow Food in Iceland and globally supports small-scale farmers, organic producers, and eateries that are committed to local, sustainable, and traditional food practices. Embracing the principles that food should be good for us, clean for the planet, fair to producers, and produced sustainably, Slow Food champions a shift back to the roots of culinary tradition.

For more information about Slow Food in Iceland, check out their website.

Reykjavik Food Lovers Tour

Your Friend in Reykjavik’s Food Lovers Tour offers a straightforward way to enjoy Slow Food in Iceland. It’s not officially linked to the Slow Food movement, but it’s a solid chance to experience the local cuisine. On this tour, you’ll get to try at least 10 traditional Icelandic foods while learning about the culture behind them from an expert guide. Our guides are excellent at sharing Iceland’s stories and traditions in a fun way. Plus, we’ve picked some top-notch restaurants for you to try out. It’s a good mix of eating and learning about Iceland’s history through its food.

Biodiversity is Most Important

The Slow Food Foundation for Biodiversity is at the heart of this movement, championing the protection of the environment, the defence of food biodiversity, and the promotion of sustainable agriculture. The foundation supports Terra Madre communities worldwide to preserve traditional knowledge and food practices through a series of global projects, such as the Ark of Taste, the Presidia, Earth Markets, and the Thousand Gardens in Africa.

Slow Food in Iceland

Among the treasures aboard the Ark of Taste are 23 unique Icelandic products that tell a story of tradition, resilience, and Iceland’s rich culinary heritage.

Traditional Icelandic Skyr

Skyr, a traditional Icelandic cheese made from cow’s milk, dates back to the nation’s earliest settlers over a millennium ago, a staple mentioned in medieval sagas and found in archaeological digs. Initially made with sheep’s and cow’s milk, the 20th century saw a shift to exclusively using cow’s milk due to changes in sheep farming practices. Often mistaken for yoghurt abroad, skyr is technically a cheese with a complex production process. The milk is heated and then fermented with a bit of the previous skyr batch and calf rennet, if needed, before the whey is separated through straining, resulting in its distinctive dense texture and tangy taste.

Traditionally produced in summer, maintaining skyr cultures through winter is crucial for continuous production, akin to making sourdough bread. While historically consumed plain, modern skyr is often sweetened and enjoyed with cream or milk. It boasts a rich nutritional profile, high in protein and low in fat. Today, skyr features prominently in Icelandic cuisine, from breakfasts to restaurant dessert menus.

The Icelandic Goat

The Icelandic goat, among Europe’s oldest and purest goat breeds, is notably rare. Brought to Iceland in 874 AD by Norwegian settlers, these small animals have played a traditional role in Icelandic farming, as seen in 18th-century artefacts. Females weigh between 35 to 50 kilos, and males between 60 to 75 kilos, with heights of 65 to 70 cm for females and 75 to 80 cm for males. Known for their short, backwards-curving horns, they are valued for their meat, milk, and cashmere-producing coats, appearing mostly in piebald, beige, or grey, with about 20% being white.

Their diet mainly consists of grass and farm-produced hay, occasionally supplemented with other feed like salted fish, a practice dating back to Iceland’s settlement. They graze outdoors from late April or early May until the onset of cold weather or the first snowfall.

Icelandic goat meat, lean and flavorful, is traditionally used in soups with potatoes, turnips, and wild herbs. Today, only a few small-scale farmers rear these goats for meat, facing challenges in maintaining the tradition due to low financial returns. The once-thriving production of Icelandic goat cashmere and traditional fresh cheeses like skyr has dwindled, especially after industrial methods of milk processing were introduced by large cooperatives.

Fermented shark

Fermented shark, known in Icelandic as kæstur hákarl, is made from the Greenland shark and has been part of Iceland’s culinary tradition for over 700 years. Originally, the meat and the shark liver oil were valuable, with the oil lighting up Copenhagen’s lamps until the late 19th century when demand declined. Traditional methods involved fermenting the shark in pits or containers, allowing it to ferment for weeks before drying it out in shelters for several months. This process, which doesn’t use additives, allows the shark to be preserved without spoiling, thanks to the cold Icelandic winter preventing bacterial growth.

Today, what was once a staple is now a delicacy, often enjoyed with brennivín, a caraway-flavored schnapps, during the winter month of Þorri. Despite its storied place in Icelandic cuisine and availability in supermarkets and gourmet stores, its distinctively sharp taste and the tradition of consuming it are fading among younger generations, with total production now at about 20 tons annually.

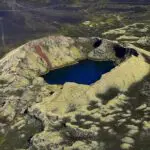

Geothermal Salt (Saltverk Salt)

Geothermal sea salt is harvested using geothermal hot springs and stands out for its purity, flaky texture, and mineral richness. Due to Iceland’s lack of firewood, traditional salt production was scarce, with some early forms, including “black salt,” made by burning seaweed. Instead of relying solely on imports for their salted cod, Icelanders sought local solutions.

A significant turn in local salt production occurred in the late 18th century with the establishment of a saltwork in Reykjanes in the Westfjords. This location was selected for its proximity to geothermal hot springs despite the Westfjords being generally known for limited geothermal energy. This initiative aimed to leverage Iceland’s geothermal resources for salt production but struggled without adequate support, leading to its eventual decline.

Recently, this geothermal salt-making process has been revitalized in the Westfjords, embracing environmental sustainability and renewing a once-forgotten tradition. Producing about 50 tons annually, with potential for growth, this method highlights a sustainable approach to reviving historical practices, contrasting sharply with the large quantities of salt still imported for Iceland’s culinary needs.

Sundried Cod (Bacalao)

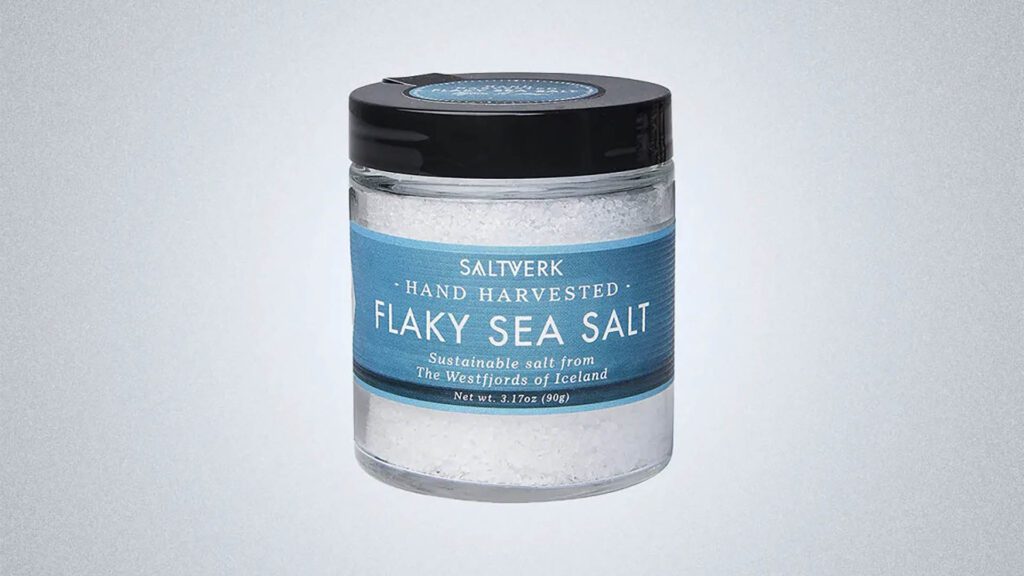

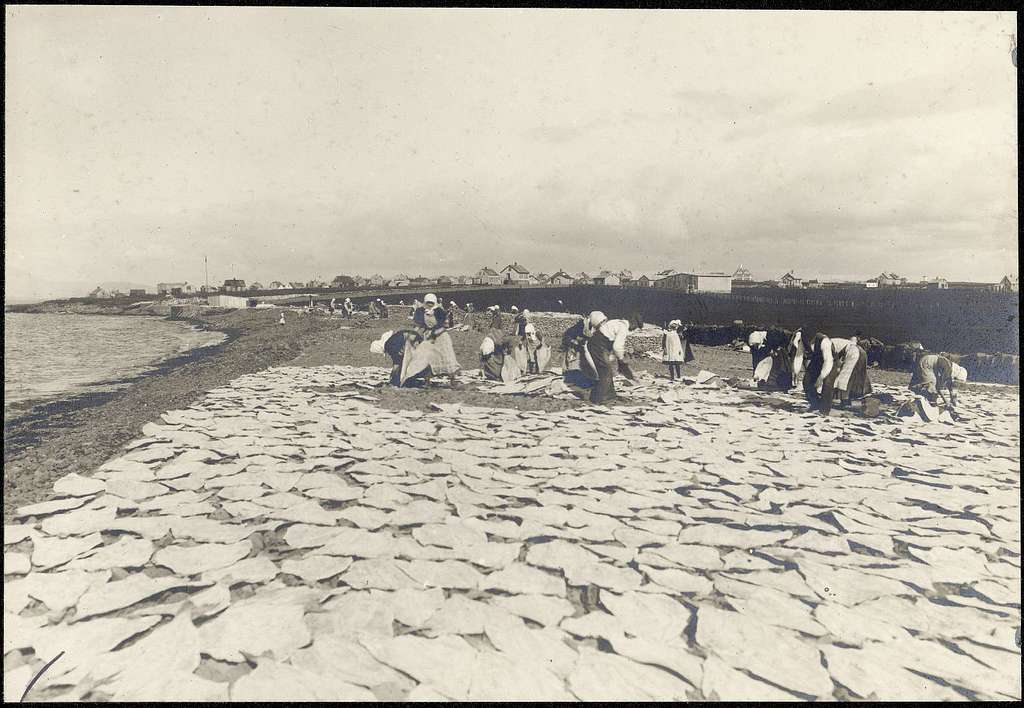

In Iceland, sun-dried salted cod, or sólþurrkaður saltfiskur, is crafted from local cod through a traditional process. Initially, the cod is cleaned, salted in layers, and then left to age, losing moisture and absorbing salt to develop its unique taste and texture. The process, which traditionally took months, can be expedited by initially brining the fish. Following salting, the cod is air-dried on wooden frames or gravel, requiring dry, sunny conditions to achieve optimal quality.

Due to the high cost of salt, drying without salting was the primary method of preserving fish in Iceland until the 17th century, when salted fish processing for export began. By the mid-19th century, sun-dried salted cod had become Iceland’s most valuable export, dominating until WWII, when frozen fish products surpassed it. Subsequently, the domestic drying of salted fish decreased, with the process moving to Iceland’s main markets, Spain and Portugal, rendering sun-dried salted cod rare in Iceland for decades.

Recently, the tradition of sun-drying has seen a revival, with sun-dried salted cod known for its yellowish colour and robust flavour. It’s rehydrated before use, commonly boiled with potatoes and butter or sheep’s tallow. Today, production is limited, mainly in the Westfjords, with the Westfjords Heritage Museum being a notable producer, highlighting the cultural and historical significance of this traditional Icelandic delicacy.

Stockfish or “Harðfiskur”

In Iceland, hert ýsa or harðfiskur refers to traditionally dried haddock, a delicacy made by lightly salting Melanogrammus aeglefinus with brine and air-drying it on wooden racks. This method, which includes drying the fish whole or as fillets, was enhanced by the 19th-century addition of salt. Optimal drying conditions require freezing temperatures and wind, contributing to the product’s unique texture and flavour. Unlike other preparations, dried haddock is eaten raw, tenderized with a mallet, and often paired with butter.

Indoor drying techniques are growing in Iceland, offering a saltier flavour and less dependence on weather, accelerating production. Historically, stockfish, including dried haddock, has been a cornerstone of Icelandic cuisine and a significant export since around 1200. Today, while cod is mainly exported, haddock remains a staple for domestic consumption. With an annual production of about 50 tons, primarily in the Westfjords, the method of making traditional dried haddock has remained consistent through the ages. Enjoyed year-round, its popularity spikes in summer and during food festivals, valued both as a protein-rich snack and for its health benefits.

Hangikjöt (Smoked Lamb)

Hangikjöt, Icelandic smoked lamb, is a cornerstone of Iceland’s Christmas cuisine. It is traditionally smoked over dried sheep dung to impart a unique flavour. Served with boiled potatoes, white sauce, and peas or as a topping on rye pancakes and bread, its preparation reflects Iceland’s adaptation to environmental changes since its settlement in the 9th and 10th centuries. With the depletion of woodlands, Icelanders turned to peat and sheep dung for fuel, establishing smoking as a key method for meat preservation.

Even today, sheep dung remains essential for smoking foods. The dung, mixed with hay, is dried for up to five years before use. Smoking has evolved from open hearths in sod houses to specialized ovens or smokehouses. The process involves dry-salting or brining the lamb, typically the leg or shoulder, without modern additives or techniques, followed by cold-smoking over sheep dung, sometimes with birch wood.

Produced across Iceland, hangikjöt’s annual production reaches 200 to 250 tons, showcasing its popularity despite competition from imported meats. Traditional smoking techniques continue both in meat processing plants and on sheep farms with private smokehouses, underlining hangikjöt’s cultural significance amidst shifting dietary preferences.

Hangikjöt is a slow food in Iceland which is great to take on the road with you, along with skyr, flatkökur and other Icelandic delicacies.

Lúra

Lúra refers to a local variety of European plaice found in the shallow, brackish waters of Hornafjörður, a southeastern Icelandic fjord. This small fish thrives due to the unique environmental conditions of Hornafjörður, making it a speciality of the region. Caught using traditional methods that have remained unchanged for decades, except for the modern use of motorboats, lúra is a key part of the local diet, enjoyed boiled, fried, dried, or pickled.

The tradition of fishing and preparing lúra spans centuries, with the community of Hornafjörður passing down this culinary heritage through generations. Historically a significant food source, today, lúra is also marketed to tourists as a unique “food souvenir,” reflecting its cultural importance. Despite its popularity, the practice of catching and preparing lúra faces challenges due to its seasonality and the risk of fading interest among younger generations.

In Höfn in Hornafjörður is one of two Slow Food sections in Iceland – the other one is in Reykjavik.

Magáll

Magáll, a smoked delicacy made from lamb flank, has its roots in traditional Icelandic cuisine as a method for utilizing less desirable cuts of lamb or mutton. The preparation involves boiling, salting, and pressing the meat, then enclosing it in a cloth sack or paper for smoking. This technique, dating back to the Middle Ages, allowed magáll to become a valued part of the Icelandic diet, often served thinly sliced over bread or alongside pancakes and syrup.

The advent of rúllupylsa in the 19th century, a technique likely influenced by Danish culinary practices, led to magáll’s decline in popularity. However, it remained a common feature in Icelandic homes, especially post-autumn sheep slaughter.

Nowadays, magáll production is scarce, largely confined to the north of Iceland, with just a few small-scale commercial producers remaining. Though not as prevalent as before, it still finds its place during the Thorri festivities, which celebrate the old Norse culinary traditions. Despite its rarity, magáll continues to be sold in speciality shops, particularly during the winter months, holding onto its place in Iceland’s cultural and gastronomic landscape.

If you want to read more about Icelandic Þorri food, check out our blog.

Rúllupylsa

Rúllupylsa, a traditional Icelandic dish, transforms less sought-after cuts of lamb into a seasoned, rolled delicacy. Prepared with local herbs like yarrow and Arctic thyme, the flank is salted, sometimes smoked, pressed, and then served thinly sliced on bread.

Originating from a late 18th-century recipe with Danish influences, rúllupylsa gained popularity in Iceland by the early 20th century. It evolved from the earlier magáll method, where meat was boiled, pressed, and smoked without rolling. By the late 19th century, rúllupylsa, also known as vöðlubjúga in older recipes, began to replace magáll in Icelandic kitchens.

In recent years, rúllupylsa has seen a revival with national competitions encouraging small-scale production. Despite its presence in many Icelandic homes and stores, the traditional practice faces challenges, with a notable decline in artisans and farming households keeping the tradition alive.

Ætihvönn – Angelica

Angelica archangelica is a remarkable herb in Iceland, valued for medicinal and culinary uses since the country’s settlement. Vikings used its roots as trade currency abroad. Traditionally, Icelanders grew it near farms for easy access, and old laws like Grágás penalized stealing it from gardens. Its Latin name and revered status, “the root of the holy spirit,” come from legends of its power to cure the plague and ward off evil.

Common across Iceland, especially near water, Angelica archangelica boosts the immune system and combats viruses, playing a key role in Icelandic health and cuisine. Its parts—stalks, roots, leaves, and seeds—are versatile in cooking, found in dishes from soups and bread to condiments in alcohol. Its roots were historically eaten with fish and butter, believed to prevent epidemics. Today, it flavours liqueurs like Chartreuse and Benedictine, and its seeds enhance the taste of Icelandic lamb, with some farmers grazing lambs on it for a unique flavour.

However, its inclusion in medical supplements has led to a pharmaceutical monopoly on its growth areas, restricting local culinary use and knowledge. Changing food habits risks sidelining this traditional herb.

Dulse – Söl

Dulse (Palmeria palmata) is a versatile seaweed, shifting in colour from purple to green, traditionally harvested in Iceland’s Breiðafjörður Bay and other western locations during August’s low tide. Its historical decline as a staple food has reversed recently, thanks to its rich antioxidant and protein content. Known in Iceland since the 9th century, dulse’s resurgence is linked to both its health benefits and culinary potential.

Originally, dulse was a valuable Norse food introduced by Celtic slaves and wives. It was highly prized, even used to make “black salt” before the import of “white salt” from Denmark in the late 14th century. Harvested dulse was soaked, dried like hay, and stored, enhancing its texture and digestibility. Consumed dry with butter, in stews, soups, or with fish, its use dwindled with the 19th-century influx of imported grains but has seen a revival as a dietary supplement and spice, with a few producers now packaging it for consumer use.

Today, dulse’s application in Icelandic cuisine is growing, yet the appreciation for this traditional, high-value product remains limited. Its potential lies in broader consumer recognition and innovative culinary uses, especially with fish.

Fjörukál – Cakile Arctica

Cakile arctica, a member of the Brassicaceae family found on South Iceland’s sandy shores, was once a vital part of the Icelandic diet, especially for its vitamin C content. Known locally as fjörukál or “sea cabbage,” its leaves and roots were consumed, particularly where traditional cabbage, or skarfakál, couldn’t grow due to harsh conditions. Traditionally harvested in early summer, it was often fermented to extend its shelf life and used in soups and porridges.

Despite its historical importance, fjörukál’s use declined with the advent of imported foods and greenhouse agriculture. However, it still holds a place in Icelandic history, notably during the 1783 Laki volcano eruption, when it became a crucial survival food. Today, its status has evolved from a survival staple to a rediscovered vegetable by modern chefs, valued for its unique taste and nutritional benefits, though it now competes with invasive plant species for survival on Iceland’s shores.

Gulrófa – Yellow Turnip

Gulrófa, or rutabaga, is a hybrid of turnip and cabbage, prevalent in Northern Europe and Russia, recognized for its purple tops, yellow bodies, and sweet, yellow flesh. Its Icelandic name highlights its yellow colour, drawing from “gulur” (yellow), with “rófa” possibly originating from Latin “rapum” or Danish “roe,” also known elsewhere as Swedish turnip or yellow turnip. A Swiss botanist first documented it in 1620, noting its growth in Sweden. Its first Icelandic mention was in 1863, praised for its cold resistance and importance in local cuisine.

Gulrófa is vital in Icelandic dishes, especially traditional lamb soup and split pea soup with salted lamb, served on Shrove Tuesday. Dubbed ‘The Orange of the North,’ it’s a Vitamin C-rich vegetable planted in spring or started in greenhouses for summer transplanting. Popular Icelandic varieties include Ragnarsrófa, Kálfafellsrófa, and Sandvíkurrófa. Despite being a staple, about a third of its production is wasted due to size standards. Recent research has explored its potential in syrup and vodka production, highlighting its suitability for Icelandic farming, its culinary significance, and its potential in sustainable food production. With a per capita consumption of 2.4 Kg annually, rutabaga is key to the local diet, offering essential micronutrients.

Icelandic Dairy Cattle

The Icelandic dairy cow, a Nordic breed, averages 470 kg for females and up to 1000 kg for males, with most being polled due to selective breeding. These cows, compulsory grazers for at least 8 weeks each summer, are a hardy breed adapted to a roughage diet. Present since Iceland’s settlement over 1100 years ago, this breed remains the sole dairy cattle in Iceland, with a current population of about 24,000 lactating cows.

Known for their diverse colours, the Icelandic dairy cow’s average milk yield is 5700 litres annually, rich in fat and protein, with some cows producing up to 13,000 litres. While milk is the primary product, income is derived from beef, hides, and dairy products like cream, butter, skyr, and cheese. Traditional milk processing methods, particularly for skyr, are of interest to preserve the milk’s unique nutritional value.

Iceland has maintained this breed’s purity since between 800 and 1000 AD, with strict import conditions preventing crossbreeding, preserving one of Europe’s oldest pure breeds. Unique milk constituents of Icelandic cows, differing from interbred Nordic breeds, may offer health benefits, such as diabetes protection in children and superior cheese-making qualities.

Recent legal changes allowing more genetic material imports and increased foreign dairy product competition pose risks to this native breed’s genetic purity and health, highlighting the need to protect and promote this vital part of Iceland’s agricultural heritage.

Icelandic Fjallagrös

Fjallagrös (Cetraria islandica) is a lichen valued by Icelanders since ancient times for its culinary and medicinal properties, often serving as a form of currency. Due to its high value, collecting it on others’ land was once strictly forbidden due to its high value, particularly for treating digestive and respiratory issues. Found in various colors and textures, it thrives in areas without winter grazing, mainly on heaths and mountains. Its collection, traditionally a task for women in North Iceland, could take weeks.

Traditionally dried on fields after harvesting, fjallagrös was crucial for Icelandic diets, especially when grain was scarce. It enhanced the nutritional value of bread, soups, porridge, and even skyr, a local dairy product. It also served as a natural dye, producing red and yellow colours for fabrics and yarns. Though less commonly gathered today due to increased imports and available alternatives, fjallagrös remains a respected remedy and is experiencing a resurgence in culinary use.

Careful harvesting is essential to protect its fragile structure, with a recommended replenishing period of 3-5 years for sustainable collection. Today, fjallagrös is incorporated into traditional dishes like flatkökur, soups, and stews. It’s recognized for its health benefits in drinks and as an ingredient in cough mixtures and teas, validating its historical significance in Icelandic culture and health.

Icelandic Settlers Hen

The Icelandic hen, or Landnámshæna, traces back to the 10th Century, brought by Irish and Norwegian settlers to Iceland. For centuries, this breed was the sole chicken source on the island, providing fresh eggs and meat until the mid-1970s, when it began to be replaced by more productive, imported breeds. Nowadays, the Landnámshæna is preserved on small farms across Iceland, thriving in diverse landscapes from fjords to valleys.

As a landrace, the Icelandic hen has naturally adapted to Iceland’s environment, developing unique characteristics with minimal human intervention. These medium-sized, colourful birds exhibit a wide range of feather colours and patterns, but cross-breed traits like feather-covered feet or beards are not accepted. Known for their curiosity, independence, and strong maternal instincts, they are excellent foragers, thriving on Icelandic vegetation and insects when weather permits. During harsher months, their diet is supplemented with organic legumes and grains.

Today, the Icelandic hen is valued more for its eggs, which, though fewer in number than commercial hybrids, are highly nutritious and high in protein. Meat is a secondary product, and historically, their feathers were used for duvets, pillows, or ink pens.

Icelandic Sheep

The Icelandic sheep, part of the North European short-tailed breeds, has been in Iceland since the settlers arrived over 1100 years ago. With a current winter population of 470,000, the unique leadersheep strain, numbering only 1,500, faces risk. Esteemed for their intelligence and ability to lead under harsh conditions, leadersheep are a distinct aspect of Iceland’s farming heritage. Icelandic sheep are renowned for their hardiness, diverse wool colours, and for being excellent foragers, surviving on natural pastures in summer and silage or hay in winter.

Adult Icelandic sheep typically weigh between 60-100 kg, with leadersheep being lighter and more slender. These sheep are primarily valued for meat, with wool and milk as secondary products. Leadersheep, however, are specially bred for their guiding intelligence and alertness. Icelandic sheep produce various products, from fresh meat to traditional delicacies like smoked sheep meat and salted lamb, integral to Icelandic culture and retail markets.

Despite their significance, leadersheep are rare, found in only 10% of flocks. With modern shifts in agriculture and competition from imported goods, the conservation of this breed is crucial. The Leadersheep Society of Iceland, with 160 members, supports their preservation, highlighting the need to protect these animals that have adapted uniquely to Iceland’s environment and played a crucial role in the nation’s survival through challenging times.

Kleinur

The Icelandic doughnut, while not unique to Iceland, is a staple in the pastry traditions of Northern Europe, with variations known as Fattigmann in Norway, Merveilles in France, and Chrust in Poland, among others. Originating in the Middle Ages, this pastry has evolved in shape and cooking methods, including boiling, frying, and pan-frying. The Icelandic version, kleinur, distinguished by its twisted shape, derives its name from the German “klein”, meaning small. The dough, enriched with eggs, buttermilk, butter, and sugar and flavoured with vanilla and cardamom, is cut into rhomboid pieces, with a hole made for twisting to achieve its signature look.

Documented in Icelandic recipes by the late 18th century, kleinur’s history likely extends further, as evidenced by the traditional “kleinujárn,” or kleinur cutter, some of which were historically made from whalebone due to the scarcity of metals. Traditionally baked for Christmas to use rare frying fat and special ingredients, kleinur remains a beloved treat in Iceland, enjoyed year-round and often served with coffee on special occasions. While older generations may stick to homemade kleinur, younger Icelanders often opt for the convenience of industrially prepared versions. Using sheep fat (tólg) for frying has largely faded from practice.

We highly recommend you make your own – homemade is always better. Check out our recipe here.

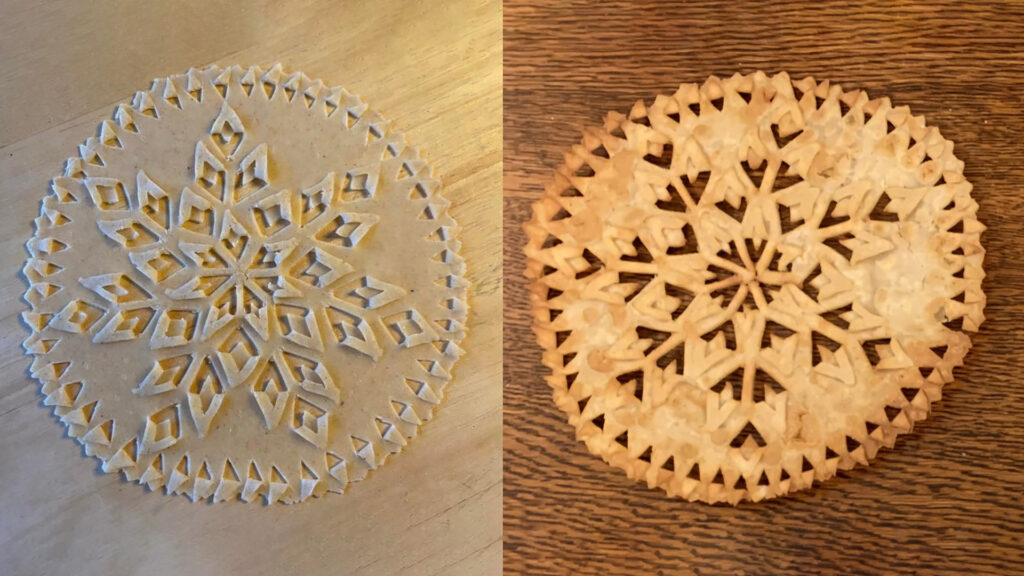

Laufabrauð

Laufabrauð, or leaf-bread, is made from a dough of wheat flour—sometimes blended with whole wheat, barley, or rye—enriched with hot milk, salt, and a hint of sugar. Rolled into paper-thin circles, typically 17-20 centimetres in diameter, it’s artfully incised with patterns using either a knife or a laufabrauðsjárn (“leaf bread iron”). These patterns, often elaborate and family-specific, involve precise cuts and creative folding to achieve their distinctive appearance. After sculpting, the bread is quickly fried in hot oil, becoming crisp and capable of being stored for weeks.

The earliest documentation of laufabrauð appears in the oldest Icelandic cookbook from the late 18th century, intended for the affluent, as evidenced by ingredients like wheat flour, cream, and butter, which were beyond the reach of most Icelanders at the time. The wider population likely used alternatives such as rye or barley flour and generic fat.

The cookbook’s author seemed to believe that laufabrauð was so well-established in Icelandic cuisine that further description was unnecessary, indicating its widespread consumption nationwide. However, by the late 19th century, the tradition of making laufabrauð had nearly vanished, coinciding with wheat flour becoming more accessible.

The revival of laufabrauð’s popularity in the mid-20th century has since cemented its status as a cornerstone of Icelandic Christmas celebrations.

If you want to make your own, check out our recipe blog!

Skarfakál

Skarfakál, thriving among West Iceland’s rocky coasts and fertile soils near seabird nests, is a Brassicaceae family member with thick, heart-shaped leaves known for their slight bitterness. Best harvested in June, its availability extends into summer based on location. Documented since the mid-17th century, skarfakál has been a crucial part of Icelandic diets, historically significant enough to influence local place names and proverbs.

Historically gathered using a specialized tool and often fermented for winter use, skarfakál’s roots trace back to the 9th-century Norse settlers, even featuring in sagas like the Grettis saga. Its abundance in the past meant it was commonly traded rather than sold, valued for its flavour and medicinal properties, particularly against scurvy due to its high vitamin C content. Traditionally, it was added to salads, soups, porridges, and even skyr, playing a vital role in preventing scurvy.

Today, while its traditional use has waned, some Icelandic farms maintain the practice, and a new generation of chefs is exploring its culinary potential, particularly in seafood dishes.

Eggs of the Great Black-Backed Gull

The great black-backed gull, or Svartbakur, is Iceland’s largest gull, recognized by its distinct black back and wings. Found across the country, from sandy shores to inland rocky glacier areas, it primarily feeds on small fish and other birds’ chicks. Its nest, built from twigs and seaweed, usually contains three large, variably coloured eggs with black spots. Historically, these eggs were a vital springtime food source, with farmers traditionally harvesting one or two eggs from a nest to ensure freshness while allowing the gull to raise its young, ensuring their return the following year.

However, the great black-backed gull’s population is declining due to food scarcity, and egg foraging has become profitable, threatening the species’ balance with humans. Modern Icelandic chefs recognize the culinary potential of these eggs and incorporate them into dishes with local ingredients while being mindful of sustainability and environmental impact. As such, they commit to using only sustainably sourced eggs, balancing culinary innovation with conservation.