Njáls Saga, also known as Njála or Brennu-Njáls Saga, is a 13th-century Icelandic saga that tells the story of blood feuds within the Icelandic Commonwealth from 960 to 1020. The saga highlights how minor offences can escalate into lengthy and devastating cycles of revenge due to demands for honour. It particularly focuses on insults to masculinity, which suggests the author’s critique of a rigid ideal of manhood. The saga also features omens and prophetic dreams, which led to debates about the author’s perspective on fate.

Check out our Private Bespoke South Coast Tour to visit the Icelandic South Coast. Don’t hesitate to contact us if you have any questions or want to change the itinerary.

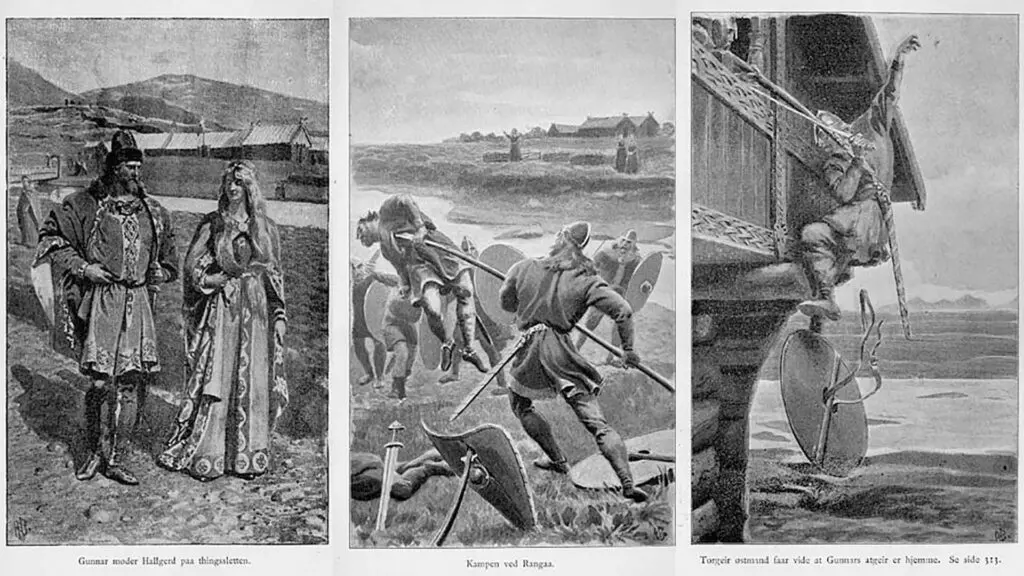

The story revolves around Njáll Þorgeirsson, a wise lawyer, Gunnar Hámundarson, an exceptional warrior, and Gunnar’s wife, Hallgerður langbrók. Hallgerður’s actions spark a feud that results in many deaths, including Njáll’s fiery demise. The saga is rooted in historical events. However, the author artistically shaped it, drawing from oral traditions to meet their creative intentions. Njáls Saga is celebrated as the longest and most sophisticated of the Icelandic sagas, often regarded as the pinnacle of the saga tradition.

For enthusiasts of this epic tale, the saga is not just a story but a journey into Iceland’s past. Many places mentioned in Njáls Saga are real, allowing fans to embark on their adventure and visit the very settings that frame this iconic saga. Visitors can explore Iceland’s rich heritage, walking in the footsteps of its legendary characters, from historical sites to the landscapes that shaped the saga’s events.

If you want to learn more about the Icelandic Sagas, check out our blogs, Icelandic Sagas for Beginners and Recommended Reads from Iceland

Interactive Map of the Icelandic Sagas and Museum

The Saga Centre, located in Hvolsvöllur in the South of Iceland, houses the Njál’s Saga Exhibition. This is right in the region’s heart, where the pivotal scenes of Njal’s Saga unfold.

The Saga Centre received a grant to map the Icelandic Sagas. The Icelandic Saga Map project features an interactive map detailing the Sagas of Icelanders and The Book of Settlements. The map is still in its beta phase and under refinement. Its functions and data accuracy are being enhanced.

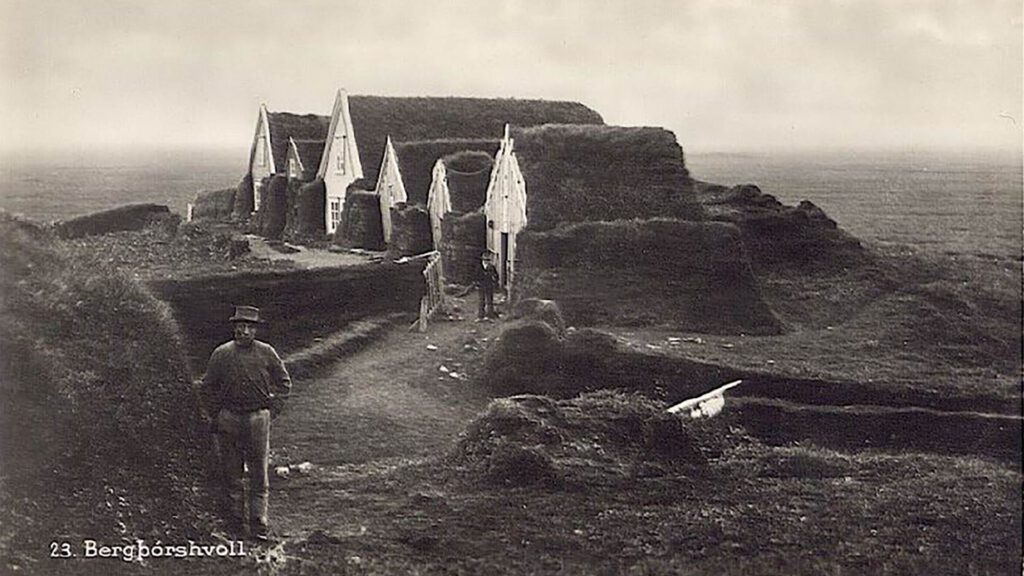

Bergþórshvoll – Home of Njáll and Bergþóra

The home of Njál Þorgeirsson and Bergþóra Skarphéðinsdóttir and their sons. The farm was burned down in an act of revenge – and everything and everyone within it, except for Kári Sölmundarson.

Bergþórshvoll is a farm in the Western Landeyjar, located on the western bank of the River Affall on a hill that rises highest in the so-called Floshóll east of the farm. The land is flat but offers a vast view from the top of the hill. The place is most famous for its role in the Icelandic Saga, Njáls Saga, as it was the home of the couple Njáll and Bergþóra. Due to the saga, various archaeological investigations have been conducted there over time. The farm site at Bergþórshvoll is protected.

Both in the past and more recently, people have tried to match descriptions from Njáls Saga of the burning with the topography of Bergþórshvoll. Early research (e.g., by Kristians Kaalund, who visited in 1877) primarily aimed to explain the sequence of events described in the saga. Still, later scholars began searching for evidence of the burning itself in the farm mound. Notable archaeologists who have conducted excavations at Bergþórshvoll include Sigurður Vigfússon, Matthías Þórðarson, Kristján Eldjárn, and Gísli Gestsson.

Archaeological Digs by Bergþórshvoll

In the late 19th century, Sigurður Vigfússon conducted archaeological research for the Icelandic Archaeological Society, aiming to connect sagas with real-world findings. His work at Bergþórshvoll involved analyzing the landscape in relation to Njáls Saga, excavating shallow trenches to discover charred wood and a white substance believed to be whey product, possibly linking it to Bergþóra’s skyr.

Matthías Þórðarson later led significant excavations at Bergþórshvoll between 1927 and 1931, uncovering around 800 artefacts from 50 structures that spanned from the Viking Age to the 19th century. This marked the largest dig in Iceland then but ended with no evidence of a farm fire, as previously speculated.

In 1951, Kristján Eldjárn and Gísli Gestsson undertook further excavations, discovering burnt ruins believed to be a large cowshed from the Viking Age, based on carbon dating. Their findings, which also summarized Matthías’ research, remain the primary scholarly record of the site’s archaeological history.

Gunnarssteinn – Gunnar’s Stone

The stone can be found near the Rangá River. It is believed that Gunnar stood on it and fought in one of Njáls saga’s most famous battles.

Gunnar Hámundarson, one of Njáls saga’s central characters, is a renowned warrior and chieftain, admired for his bravery, skill in combat, and loyalty to his friends. Gunnarssteinn is linked to a pivotal moment in Gunnar’s life. According to the saga, after numerous feuds and escalating tensions, Gunnar is declared an outlaw by the Icelandic Alþingi (the national assembly and court) and must leave Iceland.

However, as Gunnar prepares to depart, he reaches a spot that offers him a view of his beloved home, Hlíðarendi. Overcome by his homeland’s beauty and attachment to it, he decides he cannot bear to leave. He turns his horse around upon reaching Gunnarssteinn, choosing to face his fate in Iceland rather than live in exile. This decision ultimately leads to his tragic end, as his enemies later besiege his home and kill him.

Hlíðarendi – Home of Gunnar

Gunnar Hámundarson grew up at Hlíðarendi. He later lived there with his wife, Hallgerður Höskuldsdóttir, and their sons, Högni and Grani.

Located in the Fljótshlíð region of South Iceland, Hlíðarendi is portrayed as an idyllic and prosperous farm, befitting Gunnar’s standing. The saga describes the area’s beauty, with lush fields and a strategic location that played into Gunnar’s defensive strategies. His home is not only the setting for many key events in the story, including feasts, meetings, and pivotal decisions but also becomes a symbol of what Gunnar fights to protect and ultimately chooses not to leave, leading to his tragic fate.

Keldur – Home to Iceland’s Oldest House

At Keldur stood the farm of Ingjaldur Höskuldsson. There is now a turf farm there under the care of the National Museum of Iceland.

Keldur, located in Rangárvellir, South Iceland, boasts an ancient manor house and the remnants of an older dwelling among its historical treasures. This village, where life thrived until 1946, is home to around 20 structures and sits in the shadow of the Hekla volcano to its north.

Recognising its cultural significance, Keldur and its distinctive turf-covered houses were added to Iceland’s tentative list for World Heritage consideration on December 18, 2001. This nomination was refined on February 7, 2011, highlighting the village’s role in preserving traditional turf house architecture.

Historically, Keldur was first farmed by Ingjaldur Höskuldsson, a figure in the 13th-century Njáls Saga. It later became the stronghold of the Oddaverjar chieftains, including the chief Jón Loftsson, who is considered interred here. By the 13th century, the chieftain Hálfdan Sæmundsson, Jón’s grandson, and his wife, Steinvör Sighvatsdóttir, resided at Keldur.

The main residential building, dating back to the 11th century, is now Iceland’s oldest house and has been transformed into a museum. An ancient underground tunnel, discovered during a 1998 archaeological dig, links the house to the nearby stream. These tunnels, or jarðhus, are often referenced in Icelandic sagas.

Markarfljót – One of Iceland’s Biggest Rivers

Njál’s sons ambushed Þráinn Sigfússon at Markarfljót and plotted their revenge. This led to Skarphéðinn killing Þráinn by the river.

Markarfljót, a river south of Iceland, stretches about 100 kilometres. Originating from the Rauðafossafjöll massif near the Hekla volcano, its primary water sources include the Mýrdalsjökull and Eyjafjallajökull glaciers. The river carves its way through narrow mountain gorges nestled between the Tindfjallajökull and Torfajökull glaciers. It eventually meanders across the expansive sand plains close to Þórsmörk on Iceland’s southern coast. Its journey takes it initially northward, then west around Þórsmörk, before it reaches the Atlantic west of Eyjafjallajökull.

A noteworthy tributary of Markarfljót is the Krossá River, which runs through Þórsmörk and is known for its rapid and unpredictable water level fluctuations. The river’s record-high flow reached 2,100 cubic meters per second (74,000 cubic feet per second) in 1967 during a glacial flood known as Steinholt jökulhlaup.

The area’s infrastructure includes a significant milestone: constructing the first bridge over Markarfljót in 1934 near Litli Dímon. At that time, it spanned 242 meters and held the title of Iceland’s longest bridge. Subsequently, a second bridge was erected in 1978 at Emstrur, followed by a third bridge in 1992, positioned a few kilometres south of the original bridge.

Rauðuskriður – A Memory of Settlement Forests

The slave killings began at Rauðuskriður, where Njál and Gunnar shared a forest. The area is close to Stóri Dímon.

Stóri-Dímon in Rangárvallasýsla stands at the mouth of the Markarfljót river valley, rising from the river’s gravel deposits. Stóri-Dímon is a remnant of a palagonite mountain of the same type as, for example, Pétursey, Dyrhólaey, and Hjörleifshöfði. These islands were formed either in the sea or under a glacier. Still, Stóri-Dímon has been significantly eroded by the Markarfljót River and glacial floods. There is especially beautiful columnar basalt on the island’s northern part.

The name Dímon is “imported” Latin. Likely from Ireland or the Hebrides, and means “double fell” or “two mountains,” referring to Stóri- and Litli-Dímon (di = two, mons = mountain).

Deforestation Began Immediately

During Iceland’s settlement era, which began in the late 9th century, forests covered 25% to 40% of the country’s land area. These forests were primarily birch trees, with some willow, rowan, and aspen mixed in. The woods provided essential resources for the early settlers. That included timber for building homes, ships, and furniture, firewood for heating and cooking, and pastures for grazing livestock.

However, extensive deforestation began almost immediately upon the arrival of the Norse settlers. The forests were cut down to clear land for agriculture, use the timber for construction, and gather firewood. The combination of these activities, along with the harsh Icelandic climate and volcanic activity, led to significant soil erosion and degradation of the land, contributing to the drastic reduction of the forests.

Most of these forests had been destroyed by the end of the settlement era and moving into the Middle Ages. This deforestation profoundly affected Iceland’s ecosystem, leading to the loss of topsoil and decreased biodiversity that the forests supported. Efforts have been ongoing to reforest Iceland and restore some of its lost woodlands. In recent years, forests have become important in preventing soil erosion, preserving biodiversity, and combating climate change. Despite these efforts, Iceland’s forest cover today is still only a fraction of what it was in the settlement era. Which makes it one of the most deforested areas in Europe.

Þríhyrningur – The Mountain Triangle

Those responsible for the burning at Bergþórshvoll met at Þríhyrningsháls and hid there until they went to the farm. After the burning, the arsonists retreated up to Flosalág on Þríhyrningur.

Þríhyrningur is a mountain near Hvolsvöllur in Rangárvallasýsla. It comprises palagonite formation and is widely visible from the Southern Lowlands. The mountain formed on a short fissure vent during a volcanic eruption under a glacier, likely at the end of the last ice age (about 12,000 years ago). However, it could be older, as no dating has been conducted.

The mountain is named after its three peaks. Two of them are climbable by most people. Still, the third, the highest (675 meters above sea level), is only accessible to experienced individuals.