The mid-winter feast Þorrablót is held in the month of þorri, but the first day is called bóndadagur or husband day. The day is dedicated to the husband. The first day of þorri begins on a Friday between the 19th and 25th of January.

Nordic and Northern European people used the Norse calendar until Christianity took over. However, Icelanders kept using their calendar version, especially the names of the months, until the 18th century. Icelanders still use a few month names, especially þorri, góa, and harpa. The first days of those months are the husband’s day, the woman’s day, and the first day of summer, respectively.

You can read all about the calendar here. Then we have posts about individual months:

Bóndadagur

Traditionally, women went to the door the night before and welcomed þorri like a guest. However, in Jón Árnason’s folktale collections, the husband was supposed to wake up before everyone and welcome þorri.

They were supposed to get up without a shirt, no shoes and only one leg of trousers. Then they were supposed to go to the door, hop one-legged around the farm and drag the trousers leg behind them. Then they were supposed to invite other farmers from the district to a feast. This custom was relayed in Jón Árnason’s Folktale collection and is the only source for this weird custom, so it is unknown whether the storyteller was just fibbing!

Þorrablót

Þorrablót is mentioned in the Icelandic Sagas. However, as with so many things that happened a millennia ago, it is unknown how they were celebrated. But it is clear from the sagas that they included a lot of food and wine.

During the Romanticism movement and the Icelandic independence movement in the late 19th century, Icelandic students in Copenhagen met to eat traditional food, recite Icelandic poems and have a thoroughly Icelandic celebration. The Reykjavík Archaeology Association then held a þorrablót in 1880.

Þorrablót, as we know them today, a symbol of Icelandic tradition, originated during the post-World War II urbanization era when migrants from the countryside formed regional associations in Reykjavík. These groups held midwinter festivals in the 1950s and 1960s, where “Icelandic food by ancient custom” was served—a buffet of regional country foods familiar to attendees but rare in urban settings.

A New Tradition Built on Old Food

The concept of Þorramatur, linked to the month of Þorri and the Þorrablót festivals, was popularized in 1958 by Reykjavík’s Naustið restaurant. They served traditional foods in large wooden troughs, modelled after those in the National Museum of Iceland, to offer non-association members a taste of rural cuisine and to boost winter business. This initiative was a hit and quickly adopted by other restaurants and regional and student associations hosting Þorrablót festivals.

Since the 1950s, Þorramatur has evolved. What began as large association festivals in Reykjavík now includes smaller gatherings and family Þorrablóts, defined by the serving of Þorramatur. This evolution led to a standardization of foods mass-produced for the season. Recently, the tradition has returned to the countryside, reflecting local customs.

Þorramatur has adapted to changing tastes. Traditional methods like storing meat in fermented whey have been modified, offering both sour and non-sour versions to cater to modern palates. While maintaining staples like smoked lamb, fermented shark, and dried fish, the buffet now occasionally includes regional delicacies like seals’ flippers, previously rare and unfamiliar. However, it is illegal to hunt seals in Iceland, so seals’ flippers are becoming more rare.

Where can you get the þorri food?

Þorrablót are generally closed events for societies, families and workplaces. However, that doesn’t mean you won’t be able to try out the food anywhere!

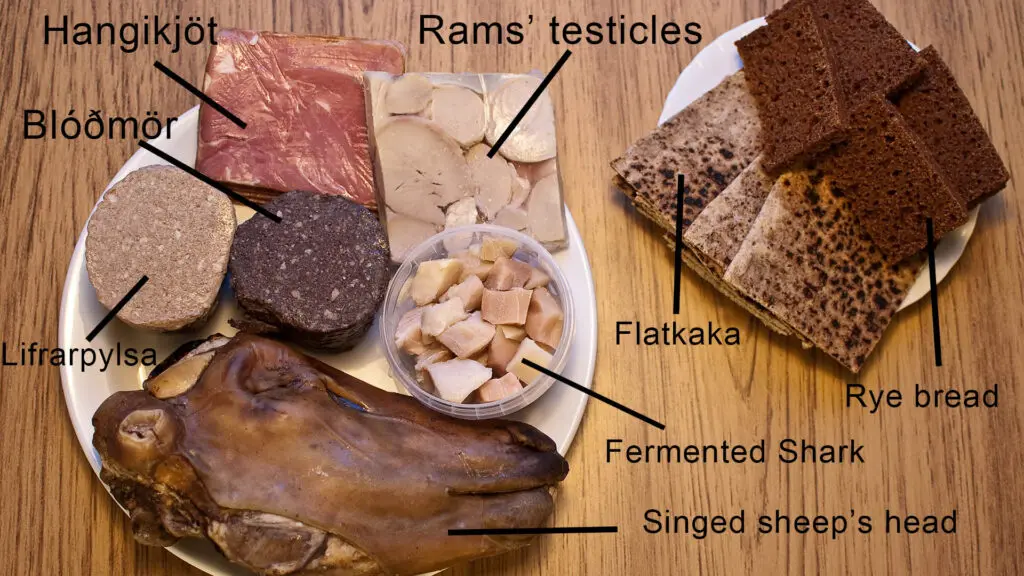

The Icelandic Bar offers a þorri plate, which includes singed sheep’s head & mashed potatoes, fermented shark, dried cod, pickled ram’s testicles, liver sausage, blood pudding, jellied sheep’s head, smoked leg of lamb, mashed beets, rye bread, flatbread & whipped butter.

Múlakaffi is another place which offers þorri food. The restaurant is known for its honest home food and if you want to try Icelandic food as Icelanders know it (homemade “mom” food), Múlakaffi is the place to go. On their website, it says: We welcome our guests at the restaurant at Hallarmúli and make sure that they leave satisfied and happy. Every day, you can choose between several well-prepared and delicious main courses. Soup or porridge, side dish and coffee are included with all meals.

Most supermarkets will also sell þorri food during the þorrablót’s month.

What delicacies are served at þorrablót?

Svið – Singed lamb’s head

Svið, a traditional Icelandic dish, is a culinary representation of the ethos of using every part of an animal. It features a sheep’s head, which is halved and singed to remove the fur and then boiled after removing the brain. Occasionally, it undergoes a lactic acid curing process.

Originating from an era when every part of a sheep was utilized, svið was once a staple in Icelandic cuisine. Nowadays, its consumption is largely reserved for the Þorri season and is a highlight of the Þorrablót festival.

A popular variant is sviðasulta, where pieces of svið are embedded in a gelatinous loaf and preserved in whey. Among connoisseurs of this delicacy, the eye is often regarded as the most delectable part of the sheep’s head.

To prepare svið, the head is placed in a pot, seasoned with salt, and partially submerged in water. Once the water reaches a boil, any scum that forms is carefully removed. The head is then fully covered in water and boiled for 60 to 90 minutes, ensuring the meat is thoroughly cooked yet still adhering to the bone. Svið can be enjoyed both hot and cold.

Folklore regarding svið

For certain individuals, consuming the ears of the sheep’s head in svið is considered somewhat taboo. This hesitation stems from an old superstition suggesting that eating ears marked with the owner’s identification could lead to accusations of theft.

Additionally, there was a belief associated with the small bone located beneath the tongue. It was thought that failing to break this bone during the preparation of svið could result in a perpetual muteness in children who had not yet learned to speak.

Súrir Hrútspungar– Sour ram testicles

Sour ram testicles are a distinctive dish, exactly as the name implies. This preparation involves a meticulous process where the testicles of a ram are first carefully removed and thoroughly washed. They are then boiled and firmly pressed into moulds, taking on a distinct shape. The final step in their preparation involves curing them with lactic acid, enhancing both their flavour and preservation.

Once prepared, they are typically sliced in a manner similar to a loaf of bread, ready to be served. This dish can be quite polarizing, akin to Marmite in its “love it or hate it” nature. Many are hesitant to try it, often due to its unconventional origin, but those who do are either staunchly in favour or decidedly against its unique taste and texture

Hangikjöt – Hung meat

Hangikjöt, translating to “hung meat,” is made from smoked meat, typically using lamb, mutton, or occasionally horse meat. The meat is carefully prepared, often boiled, and can be served either hot or cold, sliced for convenience and presentation.

Traditionally, hangikjöt is accompanied by a hearty side of potatoes smothered in a creamy béchamel sauce, along with vibrant green peas, creating a well-rounded meal. It is also commonly enjoyed with Laufabrauð, a type of traditional Icelandic bread adding an extra layer of texture and flavor to the dish. This is one of the most popular dishes to eat on Christmas Day in Iceland.

During the þorrablót festival, hangikjöt takes on a special form, often being served atop flatkaka, a traditional Icelandic flatbread.

Flatkökur – flatbread

Flatkaka, with its plural form flatkökur, is a traditional Icelandic unleavened rye flatbread. Characterized by its round, thin, and flat shape, it has a distinct dark appearance due to being fried on a pan. Historically, this bread was cooked directly over the embers of a fire, infusing it with a unique smoky flavour. As cooking methods evolved, small yet heavy cast-iron frying pans became the preferred tool for preparing flatkaka.

Today, enthusiastic home bakers often opt to bake it right on a hot plate, embracing both traditional and modern techniques. A notable distinction between homemade flatkaka and its store-bought counterpart is the inclusion of wheat flour in the latter, altering both texture and taste.

Believed to date back to the 9th century, coinciding with Iceland’s settlement period, flatkaka is a culinary legacy. It is typically served with a variety of toppings such as butter, mutton paté, hangikjöt (smoked meat), smoked salmon, shrimp salad, or pickled herring.

Blóðmör – Blood suet

This traditional Icelandic blood pudding, known as blóðmör, is a rich and savoury dish crafted from a blend of lamb’s blood and suet, mixed thoroughly with rye flour and oats. Its preparation and ingredients bear a resemblance to Scottish haggis, another classic example of using every part of the animal in cooking. In Iceland, the combination of blóðmör with lifrarpylsa, another type of sausage, is colloquially referred to as “slátur,” meaning “slaughter,” reflecting its origins in butchery and meat processing.

Historically, blóðmör was prepared by utilizing a lamb’s stomach as a natural casing, into which a mixture of suet, rye, oats, and blood was stuffed. Modern practices, however, often involve the use of synthetic casings for convenience and consistency.

Dating back to the time of Iceland’s settlement, blóðmör holds a significant place in the nation’s culinary history. Variations of this dish can be found in many countries, typically using pig’s blood instead of lamb’s. In some cases, spices and raisins are added to create a version known as “raisin blood suet,” adding a sweet and spiced dimension to the dish. When served hot, it is commonly accompanied by mashed turnips.

Lifrarpylsa – Liver Sausage

Lifrarpylsa, a traditional Icelandic liver sausage, shares a similar preparation process with blóðmör, with key differences in its ingredients. Instead of blood, this savoury sausage is made using minced liver and, occasionally, kidneys, which gives it a distinct flavour and texture.

Although lifrarpylsa and blóðmör are often consumed together and collectively referred to as “slátur,” meaning “slaughter,” it’s interesting to note that lifrarpylsa is a relatively more recent addition to Icelandic cuisine, believed to have originated in the 19th century. This contrasts with blóðmör’s deeper historical roots.

In contemporary times, slátur, encompassing both lifrarpylsa and blóðmör, is available throughout the year.

Bringukollar -Brisket

This is the fat meat of the chest of the sheep. It is boiled like other food, which is lain in whey.

Harðfiskur – Fish jerkey

Harðfiskur, a staple in Icelandic cuisine since the settlement, is a dried fish typically made from haddock, catfish, or cod, though coalfish, blue whiting, and halibut are also used. Historically, it was one of the most commonly consumed foods in Iceland, often enjoyed with butter. Renowned for its nutritional value, harðfiskur is an excellent protein source, consisting of approximately 80-85% protein.

The preparation of harðfiskur begins with selecting only the freshest fish. The fish are carefully filleted by hand, cleaned, and meticulously deboned. After this, the fillets are immersed in a brine solution, with the concentration varying between 2-5%, depending on the curing method. There are three primary curing techniques: warm air, cold air, and outdoor curing.

Outdoor curing, a traditional method, takes about 4-6 weeks. The fillets are hung in the open air, allowing them to dry naturally. For warm air curing, the process is quicker but more controlled. The fish fillets are initially frozen, then thawed and placed in a drying room where warm air circulates, effectively evaporating the water content in 36-48 hours. In contrast, cold air curing involves drying the fish in a room maintained at temperatures between -5° to 0°C.

Due to the intensive labour and the specific conditions required for curing, only about 10% of the original fish weight is viable for sale. This low yield, combined with the meticulous process, contributes to harðfiskur’s higher price point.

Lundabaggar – cured roll of lamb flank

Lundabaggar is an old Icelandic dish that is popular in þorrablót. This recipe involves a meticulous process of preparing a type of sausage using lamb’s offal.

The first step in making lundabaggar is to take lamb intestines, slice them lengthwise, and thoroughly clean them. Next, the fillets and neck meat of the lamb are prepared, ensuring they are well washed. This meat is then carefully stuffed into the intestines with a dash of salt, and the remaining intestines are used to wrap the mixture.

The distinctive feature of lundabaggar is the use of the diaphragm, or in its absence, the stomach or rumen, to encase the sausage. This outer layer is wrapped tightly around the meat-filled intestines and sewn together to secure it. It is recommended to boil the lundabaggar immediately after preparation, although if needed to be stored overnight, a light sprinkling of salt can help preserve it. The finished dish can be enjoyed fresh or preserved by curing in whey or smoking.

Traditionally, the lundabaggar were boiled and allowed to cool slowly. While it was sometimes eaten fresh, it was more commonly consumed sour. Regional variations in Iceland included salting and smoking the lundabaggar, akin to the preparation of magáll, a smoked belly flesh of sheep. These methods of preservation and cooking not only enhanced the flavour but also extended the shelf life of the dish.

Lundabaggar was considered one of the finest and most prized dishes in Icelandic cuisine,

Kæstur hákarl – Fermented shark

Greenland shark, or a similar species of sleeper shark, serves as the foundation for this distinct Icelandic dish. The shark undergoes a specialized fermentation process, followed by a drying period of four to five months. The result is a food item with a potent ammonia smell and a strong, fishy taste.

The reason for the ammonia odour lies in the shark’s physiology. Sharks, including the Greenland shark, do not urinate like other fish. Instead, waste products like urea and trimethylamine oxide build up in their tissues. Freshly caught, this shark’s flesh is toxic due to these compounds. To neutralize these toxins and make the meat safe for consumption, an ancient method is employed. The shark meat is buried underground and allowed to ferment for 6-12 weeks, with the duration depending on the season. This fermentation process reduces the harmful compounds and starts the breakdown of the flesh.

After fermentation, the shark is cut into strips and hung to dry for an additional four to five months. This extended drying further mitigates the toxicity and develops its unique flavour profile.

This is a definitive acquired taste. It is traditionally eaten with a shot of Brennivín. It should be noted the smell is much worse than the taste, and many do consider the shark to be a delicacy.

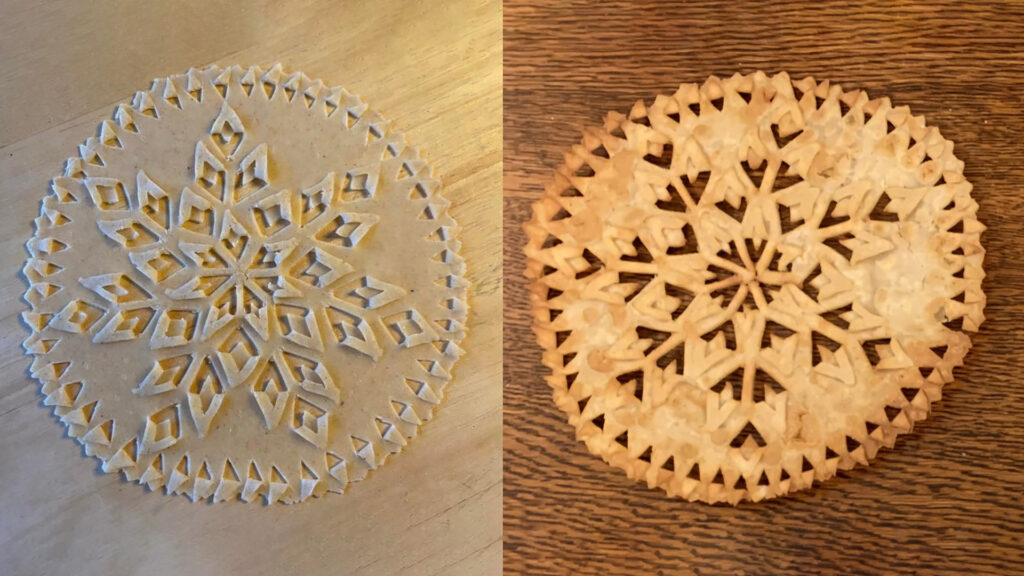

Laufabrauð – Leaf-bread

Laufabrauð, often referred to as “snowflake bread” in English, is a traditional Icelandic bread that holds a special place in the country’s culinary traditions, particularly around Christmas and during the þorri season. This delicately crafted bread traces its origins to northern Iceland.

The earliest documented recipe for Laufabrauð appears in the oldest known Icelandic recipe book, dating back to the late 18th century. Interestingly, this recipe seems to have been intended for the affluent, as it includes ingredients like wheat flour, cream, and butter – luxuries that were not commonly accessible to most Icelanders at the time. It’s believed that in more typical households, rye flour or barley would have been used in place of wheat flour, and animal fat would have been substituted for butter, reflecting the resourcefulness and adaptability of Icelandic cuisine.

For those interested in exploring more about Laufabrauð, its history, and its significance in Icelandic culture, additional information and insights can be found here.

Magáll – smoked belly flesh of sheep

Magáll is renowned for its rich flavour, derived from using the fattiest cuts of the sheep, particularly the belly. The preparation process is both simple and distinct. The belly meat is gently boiled, typically for no more than 15 minutes. This brief cooking time is crucial for retaining the meat’s texture and flavour.

While some cooks prefer to add salt to the boiling water for seasoning, others opt to leave it out. This latter method has an added benefit: the fat that rises to the surface of the water during boiling can be collected and repurposed for baking, adding a layer of resourcefulness to the dish.

After boiling, the belly meat is traditionally smoked, infusing it with a deep, smoky aroma and flavour. However, in the West Fjords, a different method is sometimes used, where the meat is hung to dry. This technique is notable as it represents a rare instance of jerky-making in Icelandic cuisine, a method not commonly employed with other meats.

Pottbrauð – Rye bread baked in a pot on a fireplace

Pottbrauð (literally pot-bread) is rye bread baked at a low temperature in or under a pot, often in a fireplace with embers. Before stoves were invented, the bread was baked under the pot. This process required a lot of skill and precision, as the embers needed to be evenly distributed around the pot and then covered, ensuring that the heat could not be reduced in one place more than another. Instead of sourdough, the bread was often soaked in whey or an acid mixture instead of water.

Cumin was a popular seasoning for pottbrauð. An iron plate was placed on top of the embers to bake the bread, and the dough was then put on top of the plate. A pot was then placed on top of the dough, and more embers were added around it to keep it evenly warm. Pottbrauð were often decorated on one side by women using a chisel shaft or stylus. Sometimes, they were flattened on a bread mould with mirror writing, allowing idioms or verses to be read. These cakes were often baked for friends and were commonly given as holiday gifts in the 19th century.

Rengi – Blubber

Whale blubber occasionally features on the menu at þorrablót, its availability largely contingent on the whaling activities of the season. In keeping with the traditional preservation methods of þorrablót foods, the whale blubber is often cured in whey, which imparts a distinctive flavour and extends its shelf life. Many consider it an almost indispensable part of the þorri season.

The consumption of whale blubber is not unique to Icelandic cuisine; it has also been a part of the diet of the Inuit in Greenland and North America.

Rófustappa – Mashed Turnip

This is simple. Boiled turnips that are then mashed.

Selshreifar – seal flippers (often cured with lactic acid)

As the name suggests, it’s seal flippers (often cured). Another type of þorramatur that is difficult to get since seals aren’t hunted professionally. The only seals that are sold have accidentally gotten caught in nets.

We could show you a picture of it, but it is a bit unsavoury looking, so we’ll make do with linking you to the former Reykjavik mayor Jón Gnarr’s X (twitter) page.

Súr sundmagi – sour air bladder

Air bladder from fish is cured in lactic acid.

Sviðalappir – singed lamb’s feet

Same as svið, just the feet instead of the head.

Svínasulta – jellied pork

For this jelly dish made with pig shanks, you start by soaking the meat in water overnight. The next day, change the water to cold, then bring it to a boil. As it cooks, remember to skim off any fat from the top. Add some onion and a few spices for extra flavour, and keep boiling until the meat is so tender it falls off the bones.

Once the meat is cooked, cut it into smaller pieces and place them in a bowl. Then, pour the hot cooking liquid over the meat. Let it cool down, and it will turn into jelly as it sets. If you want, you can also cure the dish with lactic acid for a tangy twist.

Sviðasulta – jellied sheep’s head

This jelly is made with svið. It is made in a similar way to svínasulta: pressing boiled bits of the sheep’s head into a gelatinous loaf, it’s then sliced and served cold, often with flatbread or rye bread.

Learn to make sviðasulta at home here.

Þorrablót Drinks

Þorrabjór – Þorri beer

Icelandic breweries brew quite a few beers for the Þorri season, which are then sold in Vínbúðin and Bjórland. The beer can also be found in various bars around the country. The Þorri beer season in the liquor store is between mid-January to mid-February.

Brennivín

Brennivín is a strong liqueur distilled from potatoes and flavoured with caraway. It is best-served ice cold, and like so many other Icelandic things you eat or drink, it is an acquired taste.

Other dishes:

Heilapylsa – brain sausage

Súrsaður kálfshaus – sour calf head

Siginn silungur – half dried trout

Kæst egg – Fermented eggs

Please signup HERE for our newsletter for more fun facts and information about Iceland!

[…] (new-fallen snow) and Drífa (heavy snowfall). In her story, she ran away with a boy during a Þorrablót (Þorri worship/party). Her father, Þorri, sacrificed to the gods to find what had become of her, […]

[…] can read all about the þorrablót tradition in our blog, but it is generally celebrated at the end of January and the beginning of […]

[…] grown up eating this from their parents’ baking pantries.Harðfiskur: This is possibly the most Icelandic food you will be able to get. Dried fish was Iceland’s version of bread for […]