From the brisk sea winds to the warm embrace of geothermal heat, Iceland has mastered the ancient art of preserving fish. Since the early settlers arrived, drying and salting fish, especially the famed skreið and harðfiskur, has been an integral part of Icelandic culture. These age-old techniques paved the way for delicacies served on Icelandic plates and influenced trade, politics, and even daily meals. Dive into a tale of salt, air, and Iceland’s enduring relationship with its marine treasures.

How it all started

Preserving food through air drying is the oldest method known to mankind. In Iceland, the process of drying fish has been practised since the time of settlement, and the export of dried fish, or skreið, began in the 13th century. Skreið has remained Iceland’s primary export even today. The method of making skreið involves hanging split cod in specially made sheds. The fresh air from the sea dries the fish until it becomes hard, enabling it to be stored for extended periods without getting spoiled. Recently, geothermal heat has also been used to dry fish successfully.

Over the years, “harðfiskur” has become Iceland’s most popular type of skreið. It has replaced bread to some extent and is served with most meals. Harðfiskur is usually haddock or catfish, which has been dried and beaten until it can be separated from the fish skin. It is then consumed with butter. In some cases, dried European plaice is used as a substitute for harðfiskur. This tradition has been revived, and dried plaice is now available in attractive packaging in many tourist spots around the country.

Iceland is also known for producing delicious salted cod, one of the country’s most essential seafood exports for the past two centuries. In the 16th century, foreign merchants produced salted cod for export in Iceland. At that time, Iceland was under Danish rule, and the Danish-Iceland trade monopoly strengthened the king’s power and the influence of Danish merchants. The monopoly lasted until 1787 when Icelanders could buy salt and other essentials more easily.

Icelanders Started Producing Salted Fish

Come the 18th century, saltfish production found its footing in various parts of Iceland. Interestingly, a royal decree from 1760 mandated that merchants ensure foreign experts stayed in every fishing port for a year or two solely to impart knowledge on saltfish processing techniques. By this time, the “Terraneuf method”, or what is also known as the Newfoundland method, became predominant. This method required fish to be bled, flattened, and rinsed immediately upon being caught. Before salting, the fish were set aside in containers for a few hours, ensuring moisture drainage.

The fish was almost all dried, and salting did not become widespread on a large scale until the 19th century. In the second half of the 18th century, some salted cod was exported in barrels, something like 700 barrels per year compared to 8000-10000 ship pounds of dried fish/fish jerky, and salted fish was never kept for domestic consumption.

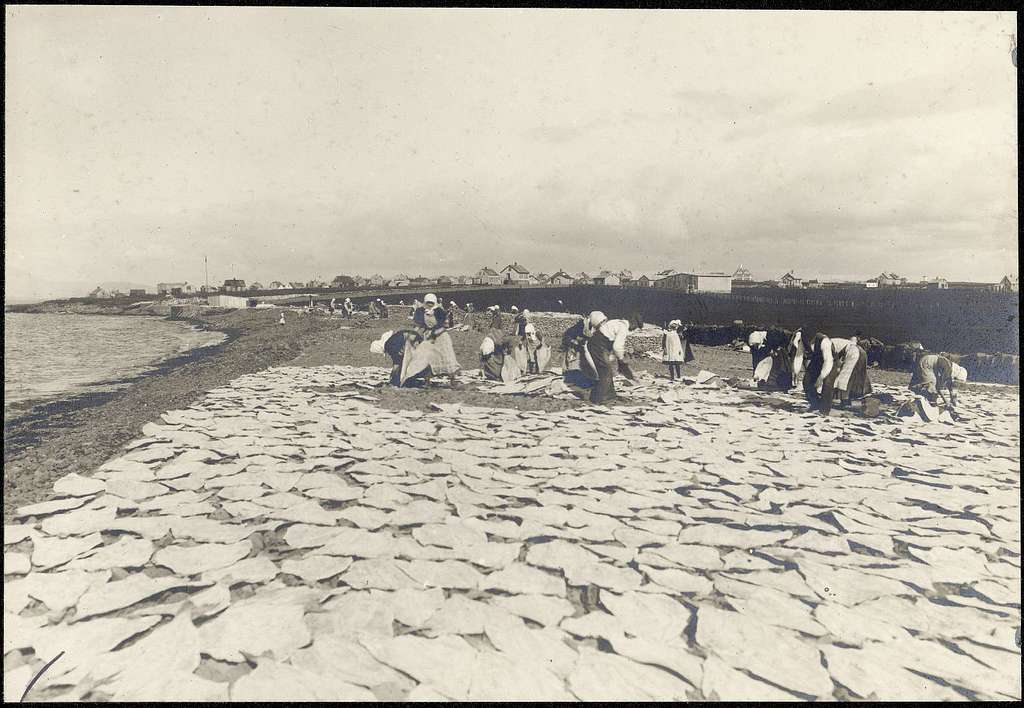

The 19th and 20th centuries heralded the zenith of saltfish processing. It was the bedrock upon which many Icelandic fishing villages emerged. Typically, fish were salted in standing water, followed by an extensive drying process that lasted anywhere from four to six weeks. This drying was labour-intensive, necessitating laying out the fish daily and collecting them by evening, weather permitting. Production involved a community effort: women, children, and the elderly handled the land operations while men ventured to the seas.

Upon landing the catch, washerwomen cleaned and prepared the fish, eventually moving them to the fields for salting. The drying and sorting process that followed was meticulous, ensuring optimal product quality for export, primarily to markets in Spain and Portugal.

Fish Exported Fresh Without Salt

However, the dynamics shifted post-World War II. Iceland experienced a labour crunch. As we got further into the 20th century, we started exporting wet-processed fish to Spain and Portugal, where it was dried more affordably. Saltfish production witnessed a steady ascent until the 1930s, with exports occasionally reaching up to 80 thousand tons annually. Yet, as the 20th century wore on, technological advancements and improved transport options favoured icefish exports, leading to a gradual decline in traditional saltfish production.

Iceland in the Eye of the Beholder

In the 18th and 19th centuries, embarking on expeditions to exotic places became increasingly popular. One of those places was Iceland.

In 1857, the French prince Jerome Napoleon, embarked on an Icelandic adventure accompanied by a grand entourage. Charles Edmond, who was part of this journey, chronicled the experience in his book “Voyage dans les mers du Nord de la corvette, La Reine Hortense”.

“Upon our arrival, we encountered Icelanders—many of whom were engrossed in drying and packaging fish. They regarded us with serene and friendly eyes. As we walked past, the men often paused, tipping their hats and offering quiet farewells. Their reactions to our presence seemed slightly bemused. Our experience felt reminiscent of the Duke of Genes’s visit to Versailles during the era of Louis XIV; in this foreign land, it was we who felt the surprise of being the outsiders.

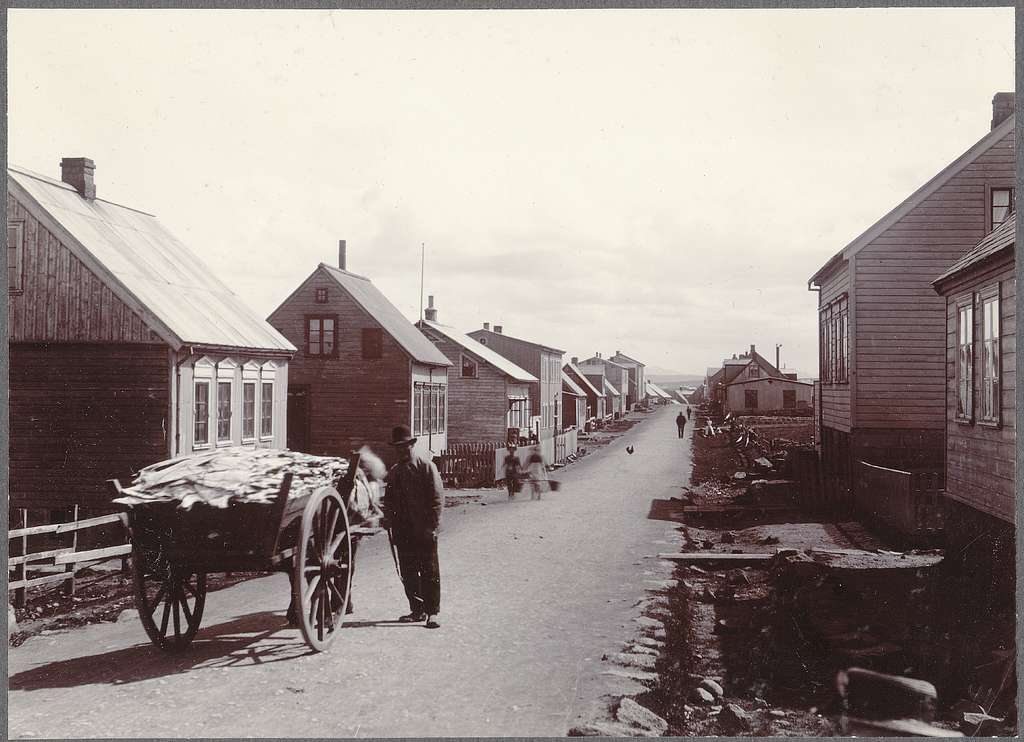

The town itself presented a sombre and desolate facade. Here and there, one might spot ancient wooden houses painted in a stark red, signifying the dwellings of officials and prosperous traders. Yet, inside these homes, nothing particularly extraordinary caught the eye. It was the everyday Icelander, the common man, who truly captivated the visitors, drawing more attention here than perhaps anywhere else in our travels.

The air in these turf houses carries a challenging aroma for outsiders. The pungent scent of dried fish melds with the sharp tang of rancid fish oil and the sour undertone of fermented milk. Fresh sheep hides and the metallic scent of animal blood, often left to coagulate in bowls for culinary uses, can be overpowering. Many foreigners, upon visiting, find themselves preferring the harshness of the Icelandic climate to the sensory assault inside the local farmsteads.”

The English botanist William Hooker was among the people to visit Iceland in the fateful summer of 1809 when Jørgen Jørgensen declared himself the king and protector of Iceland. William Hooker wrote a travelogue about his experience in the country, and this was his description of Reykjavik when they just arrived.

“Not long after signalling for assistance, a boat approached, carrying a group of porters. While not the most refined group—indeed, their appearance was a bit unkempt, and they had a noticeable odour—they provided a much-needed respite from the monotony. Their unique looks became a subject of amusement among our group. Their facial expressions didn’t reveal anything particularly out of the ordinary, with most having a broad complexion. Height varied among them; while some were rather short, a couple towered at almost 6 feet. Facial hair ranged from dense beards to what looked like the aftermath of a hasty shave with a blunt instrument. Their hair, untouched by combs, cascaded in tangled locks, which sadly seemed a haven for lice.

Their attire was simple yet functional. Woolen shirts paired with waistcoats, a blue wool jacket, and matching trousers made up their ensemble. The predominant material was coarse, undyed wool, complemented by horn buttons, likely imported from Denmark. Their socks, made of rough wool, were paired with shoes crafted from sealskin or sheepskin. A unique feature was their mittens—knitted like the socks but designed with two thumbs. This allowed fishermen to switch sides when one became wet, ensuring the palm remained dry. Their hats, reminiscent of those worn by London’s coalmen, were notably foreign in design, intended to shield against rain with their broad brims.

In their interaction with Mr. Jørgensen, they were animated, often using emphatic gestures. Their appetite was evident as they eagerly consumed our provisions, showcasing impressive dental strength by effortlessly breaking our hardest biscuits. They also had a penchant for tobacco, with even the younger boys extending their hands for a share.

Our arrival seemed to be an event as around a hundred locals, mainly women, gathered at the shore, hollering in welcome. Both groups, ours and theirs, exchanged mutual stares of curiosity. Their primary task during our landing appeared to be fish drying. We observed some spreading fish out to dry, others transporting fish on handcarts, and a few stacking them, placing stones atop to ensure they remained flat. This labor-intensive task was primarily executed by women, some of whom had a robust physique. However, their hygiene left something to be desired, and a potent, rancid aroma permeated the air as we walked by. One couldn’t help but notice the tightness of their clothing, a tradition from childhood intended to flatten the chest. While practical for the Icelandic climate, from an outsider’s perspective, the fashion seemed to detract from their natural stature.”

The Salted Fish Plains

During the first half of the 20th century, saltfish stood as a prominent export for Reykjavík. On clear days, one could see fish-drying grounds scattered across the city, where the sun would gleam off the white saltfish. Prime locations like Kirkjusandur, Ánanaust, and Þormóðsstaðir hosted these vast drying expanses. While these grounds were largely man-made creations, most have since been replaced by infrastructure and buildings. However, a preserved drying ground remains close to Háteigskirkja Church and the old College of Navigation, now part of the Reykjavík Technical College.

The prominent fisheries enterprise, Kveldúlfur, extensively utilized this site during the 1920s and 30s. The company’s factories were nestled on Rauðarárholt hill, surrounded by these drying grounds. Their primary catch, cod, was preserved using salting techniques. Fresh fish was layered with salt, drawing moisture and creating a solution to cure the fish.

After a curing period, the fish was washed and laid out in these grounds to dry under the sun. The drying duration lasted between four to six weeks, where fish was spread on rocks or wooden pallets. It would dry throughout the day on sunny days, only to be stacked and covered with sailcloth at night. Rainy spells meant the fish had to be hastily collected. This saltfish production, a seasonal affair from spring to autumn, saw everyone participating – from men and women to children. Production soared until the 1930s, but with the advent of freezing technology in the 1940s, saltfish production waned. Spain and Portugal remained the chief markets for this delicacy.

This looks Spanish To Me

The phrase suggesting that something “looks Spanish” to someone, indicating its strangeness or peculiarity, can be traced back to at least the second half of the 19th century. While earlier sources might exist—some dating to the mid-19th century, as per the University Dictionary—the record is sparse. The German expression, “es kommt jemandem spanisch vor,” shares the same sentiment.

This saying’s origin is often attributed to Protestant factions that viewed certain Spanish customs unfavourably, customs which were integrated by the German Emperor Karl V (1500-1558), who also reigned as the king of Spain. Historically, it’s believed that this phrase made its way into Icelandic via Danish, as the expression “det kommer mig spansk for” was recognized in Denmark as early as the 18th century, though it has since fallen out of use.

A popular theory links this saying to Iceland’s unique Spanish and Portuguese wine import laws. With prohibition taking effect in 1915, all alcohol imports to Iceland ceased. It’s worth noting that during this period, Spain and Portugal were Iceland’s primary salted fish customers, and in exchange, Iceland imported wine from these nations. The prohibition disrupted this trade balance, prompting both countries to threaten an end to their saltfish purchases unless wine imports resumed. Iceland reinstated wine imports from the two Mediterranean nations to maintain this crucial trade relationship in 1922.

Salted Fish in Portugal: A Culinary Heritage

Salted fish, especially cod, holds a unique place in Portuguese culinary history. Interestingly, while Portugal has a vast and diverse marine life, the seas around the country have never been home to the large cod species. This fish, often weighing up to 40kg, is native to the colder waters of the North Atlantic.

The tradition of preserving fish through salting can be traced back to the 9th century with the Vikings. They dried their catch for long voyages. The Basques, and later the Portuguese, adopted this method. However, the game-changer for Portugal came in 1497 during their expedition to Newfoundland, Canada. Here, they found an abundance of cod. Given the Atlantic climate, they realized that drying, the method used by the Vikings, was less suitable. This led the Portuguese to turn to their tried-and-true method of preservation: salting. This decision marked the beginning of the bacalhau era in Portuguese cuisine.

By the 16th century, the trade of salted cod had grown immensely. Portugal played a crucial role in this trade alongside England. Over time, salted cod transitioned from being an everyday staple to a dish appreciated by all classes in Portugal.

Still a Major Consumer of Salted Fish

In the contemporary era, while Portugal remains a major consumer of salted cod, a significant portion of the cod is now imported, primarily from Norway. It’s worth noting that Iceland, still exports a considerable amount to Portugal, as well as Spain and Italy.

Today, any visit to Portugal or a Portuguese festivity, especially during Christmas, will feature dishes made from this beloved fish. Bacalhau is more than just a dish; it represents a melding of history, tradition, and culinary expertise. So, when you’re next indulging in a Portuguese meal, take a moment to appreciate the rich history behind that serving of salted fish.

How to Cook Salted Fish?

And finally, check out our blog post with two different recipes for salted fish. Depending on the type of salted fish you get, you might need to rinse the fish in water before cooking it to get rid of some of the salt. If you’ve bought sundried fish, like they were done back in the day (and sometimes still are), you will have to rinse it. If you buy lightly salted cod steaks, then there’s no need to rinse it.

How to Rinse Salted Fish

Place salted fish in a large container and run fresh cold water over it to rinse it. Use approximately 3 litres of water per kilogram of fish, changing the water thrice during the rinsing period. If the fish is rinsed using running water, one day is enough. Change the water twice for five litres per kilogram of fish and again after 36 hours with 5-6 litres of water. If the water is never changed, use 18-20 litres per kilogram of fish. Remember to extend the rincing time for thicker pieces. After rinsing, cool or freeze the fish immediately if it is not cooked.

Where to Get Delicious Salted Fish in Reykjavik?

You will be able to find salted fish in most fish restaurants in Iceland, but our two favourite places to get salted fish are Dass and Þrír Frakkar.

Dass is a new restaurant that opened on Vegamótastígur, close to Laugavegur shopping street. You can get oven-baked saltfish there, which is very good, but you can also get fish soup, which we highly recommend as well.

Þrír Frakkar is a well-established restaurant in Baldursgata. If you want to try out whale meat or horse meat as well, it is a fun restaurant to try out.