The history of beer in Iceland is a story of evolution and persistence. It stretches back to the times of the Norse settlers, navigating through an extensive period of prohibition in the 20th century, and emerges into today’s burgeoning craft beer scene. This blog aims to present a clear, concise chronicle of beer’s journey in Iceland. It is a journey that mirrors the nation’s own growth and resilience. Let’s delve into the facts, the influences, and the key moments that have defined Icelandic brewing.

If you would like to taste some of Iceland’s delicious beers, we recommend you check out our Reykjavik Beer & Booze tour and Reykjavik Microbrewery and Distillery Tour.

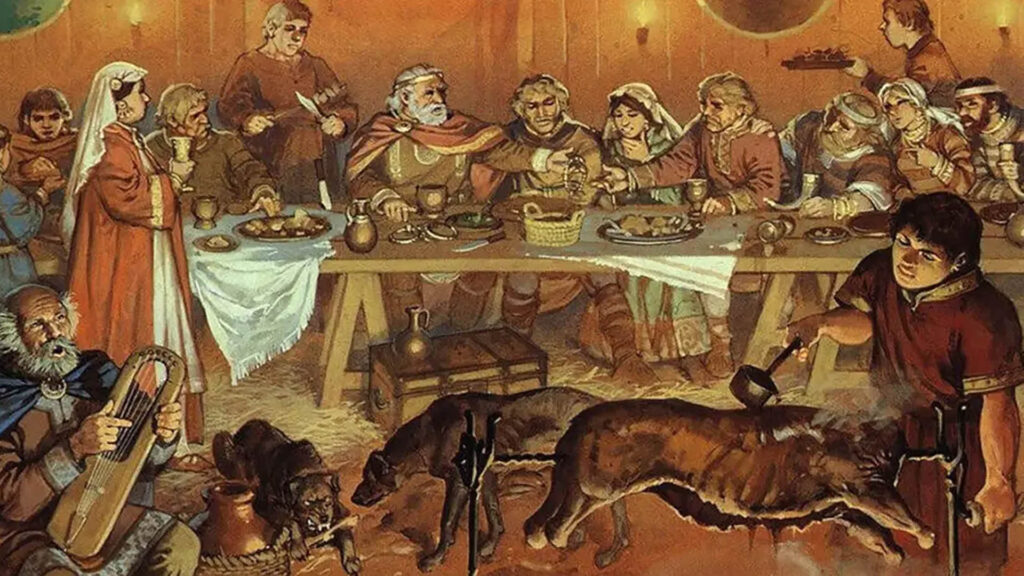

The Norse Settlers and Their Ale

It is known that the Norse settlers brought their brewing knowledge with them from Norway. Stories preserved in the Icelandic sagas show this clearly.

One such story is about Þórhallur Ale-Hood, called Ölkofra þáttr. “Ölkofra þáttr,” also referred to as the “Tale of Ölkofri” or “Tale of Ale-Hood,” belongs to a minor Old Norse prose category called a “þáttr,” which is associated with the sagas of Icelanders. Its preservation is credited to the 14th-century Möðruvallabók manuscript, alongside a few other copies made post-Reformation. This narrative serves as a critique of the medieval Icelandic Commonwealth’s legal system.

The tale centers around a man named Þórhallr, more commonly known as Ölkofri or “Ale-Hood” due to his usual attire. Ölkofri, an ale brewer by trade, inadvertently ignites a precious woodland owned by six influential Icelandic chieftains. In response, the chieftains brought a lawsuit against him at the Althing, the legislative assembly, with the intention to outlaw him. However, thanks to the intervention of unexpected allies, Ölkofri avoids this outcome.

Interestingly, the protagonist’s profession as an ale brewer and seller at the Icelandic Alþing indirectly affirms that barley was cultivated in Iceland during the concluding years of a warm phase known as the Medieval Warm Period. With the advent of a colder climate and shortened growing seasons, grain cultivation became unfeasible in the region.

Not only did they brew beer in Iceland, but there are also sources of importation of alcoholic beverages. The beer that was imported was called beer, while the one that was brewed in Iceland was called ale.

History of Beer Brewing in Iceland

From the initial centuries of Icelandic settlement until at least the 17th century, corn beer, predominantly brewed from malted barley—known locally as mungát—was the favored celebratory beverage in the country. The term ‘beer’ was initially reserved for imported ales of this kind.

Crafting ale required just three simple ingredients: malt, water, and yeast, typically obtained from the preceding brew. It’s plausible that local brewers also added tree bark or juniper berries to their ale, a practice suspected to have originated among early Norwegians.

Hops, introduced to the Nordic regions in the 12th century, enhanced the flavor and extended the shelf life of ale, guarding it against spoilage. Equipment used in the brewing process was referred to as ‘ale tools’ or ‘heating tools,’ with dedicated ‘heating houses’ established in larger residences for this purpose.

How Was Beer Brewed?

Beer production typically involves a series of steps, from malting the barley to releasing the sugars necessary for fermentation. This malt was then dried, ground, and mixed with boiling water to extract the sugar, resulting in a substance known as wort. Following the addition of hops and boiling, the wort was left to ferment, with yeast added once the temperature moderated.

The beer was then transferred to barrels to age for a few days. During fermentation, a layer of foam, known as krausen, formed and was collected to ferment the subsequent batch. This is an ‘over-fermentation’ method, so named because the yeast remains at the top instead of sinking, as in ‘under-fermentation.’ The latter, a bottom fermentation technique, was pioneered by German monks in the 1500s and is now predominantly employed in beer production, although top-fermented varieties like Porter and Ale remain available.

The cessation of barley cultivation near the end of the Middle Ages led to declining domestic beer production, but malt imports persisted for centuries. The daily beverage for Icelanders became a blend of whey and water. Beer remained an occasional drink, used for festivities due to the grain scarcity, which may have influenced the nation’s alcohol culture.

During the 19th century, local bakers brewed and sold beer, among other reasons, to retain yeast for bread making. However, a law enacted on January 12, 1900, outlawed the brewing of alcoholic beverages and alcoholic malt beverages in Iceland.

Beer and Ale in the Middle Ages

During the Middle Ages, the word “beer” began to be used for imported ale flavoured with hops, rather than Myrica gale or other herbs. This imported ale had a longer shelf life than the domestic version. Depending on its origin, it was called Hamburg Ale, Rostock Ale, or Lübeck Ale.

The traditional Myrica gale ale was used to distinguish it from the imported variety. Icelanders purchased ale from merchant ships and foreign fishermen, who drank it almost exclusively because it was less perishable than water in barrels. Some sources even suggest that Icelanders were so addicted to imported ale that they would settle on merchant ships during trade fairs and drank until the supplies were exhausted. However, after the trade monopoly was tightened towards the end of the 17th century, brennivín became a more common drink as it was more profitable for merchants to import.

Beer Drinking in Iceland

In the 19th century, the popularity of beer increased again, mainly imported beer from Germany and Denmark, but also English varieties. A lot of beer was produced at home if you consider the amount of imported malt extract at this time. Bakers brewed ale to maintain the yeast they used to make bread. They were then able to sell the by-product, the ale, especially in places outside of Reykjavík where imported beer was less common. There were attempts at commercial ale brewing in Reykjavík, among others, in the building of the Ísafold printing house by Guðmundur Lambertsen, a merchant who ran a small shop there after the middle of the century. Before the alcohol ban, beer was sold in general stores.

In 1891, the first ale tax was imposed in Denmark and was based on all ale with more than 2.25% alcohol content. Light lager was then advertised as “tax-free”. In 1917, a new tax rate was introduced for light lagers, but only top-fermented ale, white ale and so-called ship ale were exempted. Beer types that were advertised in Icelandic newspapers around and after the turn of the century 1900 were lager or “Bavarian beer”, porter, malt extract (malt beer), Vienna beer, white beer, pilsner and export (strong beer) from the Danish breweries Carlsberg, Tuborg, Marstrands Brewery and De Forenede brewery.

Importation Ban, Prohibition and Beer Ban

In January 1900, it was decided to ban all production of alcohol in the country, but it was still allowed to import it. In 1908, there was a referendum on whether or not to ban alcohol. It was approved with about 60% of all votes, but it took 7 years to implement it. In 1915, a complete ban on alcohol came into effect in Iceland, but in 1922 it was allowed to sell. In 1915, Iceland implemented a total ban on alcohol. However, in 1922, the country allowed the sale of wine due to trade agreements with Spain.

On February 1, 1935, a referendum led to the complete abolition of the alcohol ban for most types of alcohol, except for alcoholic ale and beer. The reasons behind this decision were quite complex. The original draft of the strict alcohol law in 1934 allowed for the production of alcoholic beer in Iceland. However, Pétur Ottesen, who championed abstainers’ interests, strongly opposed this provision. Hermann Jónasson, chairman of the Progressive Party, also opposed the importation of alcoholic beer since it would cost the country foreign currency, which mainly went to Denmark. Thus, the provision was changed to ban the import of alcoholic beer.

Various speakers put forward arguments for this ban, such as the belief that drinking beer led to alcohol addiction among young people. They also argued that ale being cheaper than strong wine encouraged alcohol consumption among working people, making it easy to curb the smuggling of ale. Supporters of the law’s main argument was that they would eradicate home brewing and alcohol smuggling. The law was passed and prohibited the importation and sale of alcoholic ale.

Icelandic Pilsner and Christmas Ale

During the Prohibition era, various types of ale were produced, such as pale light ale (also known as “pilsner”), non-alcoholic mead, malt ale, and dark ale (also known as white ale or Christmas ale) with a maximum alcohol content of 2.25%. In 1913, the Egill Skallagrímsson brewery was founded and initially produced only non-alcoholic ale due to the ban on alcohol. Some 17 years later or in 1930, Ölgerðin Þór was founded in Reykjavík and competed with Egill for the sale of light beer and lager until Egill acquired Þór in 1932. In 1966, Sana hf in Akureyri started production of light ale. In 1978, it merged with the Reykjavík distribution company Sanitas.

The Occupation Force Got Beer

During World War II, Ölgerðin received an exemption to produce Polar Ale, an alcoholic beer for the British occupation forces. When the US Defense Forces took over the Keflavíkur station, Icelandic beer was produced for sale with a special exemption. This beer was initially called Export Beer and had an alcohol content of 4.5%. It was later renamed Polar Beer in 1960. In 1966, Sana hf. Akureyri also produced alcoholic ale for export called Thule Export. In 1984, Viking Beer was launched primarily for export, and foreign embassies were exempt from the beer ban. The beer could also be purchased at the duty-free port at Keflavík Airport for local consumption.

The Principle of Equality Made Beer More Accessible

In 1965, crews of aircraft and cargo ships were permitted to bring in a limited amount of beer when entering the country. In 1979, Davíð Scheving Thorsteinsson purchased a case of beer at the duty-free shop on his way to Iceland and applied the principle of equality when he was stopped at customs. This led to a change in regulations, and all travellers were subsequently allowed to buy a certain amount of beer when arriving in Iceland. However, in 1980, only three types of imported beer (Löwenbräu, Beck’s and Carlsberg) were available as Icelandic beer was not sold then.

The beer ban was frequently debated, and many bills were proposed but never passed. In the 1970s, companies were established to import and sell wine and beer ingredients specifically for home brewing. Still, there was some controversy surrounding this importation, and there were talks of banning it. In 1978, the “yeast affair” arose when the Ministry of Finance suggested removing yeast from the “free list” of products anyone could import. From 1928 to about 1970, the state monopolised yeast due to an amendment to the liquor law, but yeast importation became free afterwards. However, like the other beer bills, the yeast mass destruction bill never passed Parliament.

Beer Substitute – An Abomination?

In the mid-1980s, many people in Iceland were tired of the ban on beer. Pub culture was emerging in Iceland, as in the rest of the Western world. As a result, a substitute for beer was created, a mixture of wine, vodka, whiskey, and light ale. This drink was about 5% strong and resembled beer.

The first authentic pub to open in Reykjavik was Gaukur á Stöng, decorated according to the German model. The popularity of this drink led to more places making their own version. Though, most agreed that it was not comparable to beer. At that time, people were becoming more vocal about the abolition of the beer ban.

Although some people did not like the beer substitute, it became popular. A price survey by the newspaper DV in March 1984 showed how widespread the drink was. Foreign tourists were surprised to learn that beer was prohibited in Iceland. Locals suggested ways to get good beer, such as brewing it themselves or buying it at the duty-free shop. Beer was also sold on the black market by sailors who brought it into the country. 24 beers cost back then 1300-1500ISK on the black market. That’s about 19000-22000ISK in today’s money or 142-164 dollars. Today, the same amount of beer in the state liquor store costs about 8000-11000ISK.

However, complaints about bad behaviour around pubs attributed to the beer substitute led to its ban in 1985. The police even confiscated beer-substitute mixing equipment from a brewing shop. A new regulation forbade pubs from mixing the drink, but customers could still order and mix the ingredients themselves. Tavern owners and beer enthusiasts protested the ban by marching between pubs in the city centre and pouring beer substitutes.

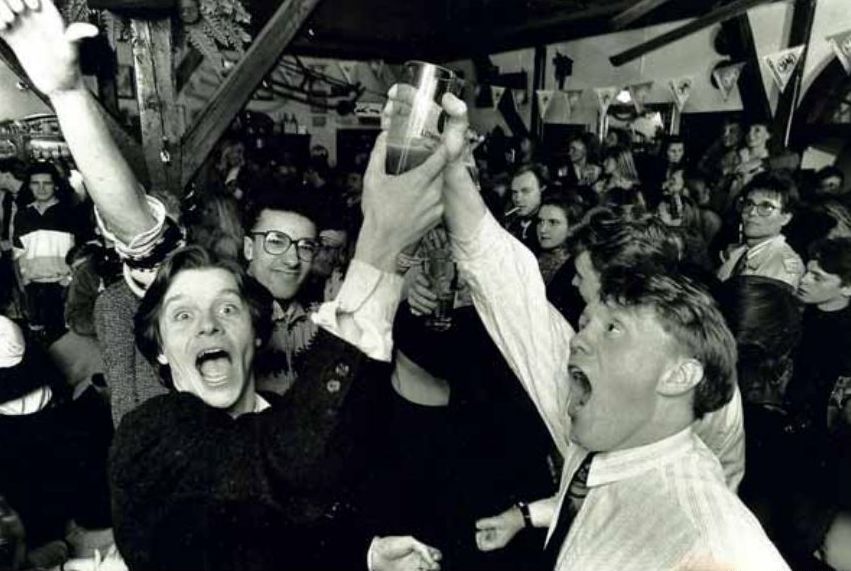

The Beer Ban is Finally Lifted!

On March 1, 1989, the ban on selling beer was lifted in Iceland. The State Liquor Stores in Reykjavík initially had five types of beer. They were Egils Gull from Ölgerðin, Löwenbräu, Sanitas Pilsner and Sanitas Lageröl from Sanitas, and Budweiser from the United States. However, imported brands like Kaiser Premium from Austria, Tuborg, and Pripps from Denmark, were added soon after. Since then, beer has become the most popular alcoholic drink in the country, with lager being the most preferred. However, the introduction of new domestic brands has increased the popularity of other types of beer in recent years.

In the 1990s, the competition between beer brands was intense. They made every effort to secure the market share of their brands for light-lager beer. Traditional advertising was prohibited, resulting in the competition taking on strange forms. Sanitas changed its name to Víking hf in 1994 after its most popular beer; in 1997, it merged with Sól hf. In 2001, the company joined Vífilfell, now known as Coca-Cola Europacific Partners. The company’s brewery is still located in Akureyri. In 2006, Bruggsmiðjan, the country’s first microbrewery, opened on Árskógssandur by Eyjafjörður. Two microbreweries, Mjöður hf. in Stykkishólmur and Ölvisholt Brewery in Flóahreppur, were added in 2007. Borg Brewery, a microbrewery, was opened by Ölgerðin in 2010. These breweries have a small production capacity compared to the two large breweries. Still, they can respond quickly to market trends using the flexible production line. They also export on a small scale.

The Icelandic State still has Alcohol Monopoly

The Icelandic state has exclusive rights to the retail sale of alcoholic beverages in retail stores through the State Alcohol and Tobacco Store (ÁTVR). The Liquor Act enacted in 1998 requires a permit to import alcohol for resale, wholesale, retail, or production in Iceland. However, everyone is free to import alcohol for personal use. ÁTVR has the exclusive right to retail alcohol. Private parties can only engage in resale in wholesale alcohol or alcohol sales consumed locally, such as in bars and restaurants. Although there have been attempts to pass a law allowing the sale of light wine and beer in general stores, it has not succeeded.

Recently, online stores have started selling alcohol online for private use as a form of protest. This is because people can freely order alcohol from abroad online. Still, Icelandic stores are not allowed to sell alcohol online. Stores like Costco, Heimkaup, Bjórland, Nýja vínbúðin, and more sell alcohol online, and while it is illegal, the government has not enforced the law.

Due to the ban on alcohol advertising, some breweries in Iceland have produced light beers with less than 2.25% alcohol content that bear the same name and use the same label as the stronger type. The word “light ale” or alcohol percentage appears in small print on the ad. Light beer is often difficult to find in stores because only a small amount is produced, primarily for advertising.

Bum in Icelandic is derived from Baron?

The Icelandic term for ‘bum,’ ‘róni,’ is widely believed to be an abbreviated form of the word ‘baróni.’ The etymology of ‘baróni’ is quite fascinating. It is a portmanteau of ‘bar’ and ‘róni.’ The latter part influenced by the term ‘lassaróni,’ used to denote a bum, vagabond, or habitual drunkard. ‘Lassaróni’ originates from the Danish ‘lazaron,’ meaning a tramp, which itself is derived from the Italian ‘lazarone,’ signifying a leper. The root of this word harks back to the biblical figure Lazarus. Although ‘lassaróni’ saw frequent usage in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, it has since fallen out of common parlance. The words ‘barón’ (baron) and ‘lassaróni’ coalesced to form ‘baróni,’ which was eventually shortened to ‘róni.’

In the 1930s, Hafnarstræti underwent a transformation and gained notoriety for its bars. One notable establishment was Bar Reykjavík, frequented by men known as Bar-rónar. The term ‘í strætinu,’ or ‘in the street,’ was often used to describe vagabonds, indicating they spent a significant portion of their time on Hafnarstræti (Harbour Street). Bar Reykjavík was situated in the building currently occupied by the Italian restaurant Hornið, which has been there since the late 1970s, and the renowned Bæjarins Bestu hot dog stand is situated just behind it.

Other former drinking establishments include Hotel Iceland, which once stood on what is now Ingólfstorg Square. This grand edifice, however, met a tragic end when it burned down in 1945.

The Pigsty – A Notorious Drinking Hole in Downtown Reykjavik

Svíanstían, or the Pigsty, was a well-known establishment located in Aðalstræti and operated for many years. The name alone implies the type of atmosphere that prevailed there.

Before the introduction of the Good Templar movement in 1884, it appears that Icelanders consumed a significant amount of alcohol, especially in the capital. This is supported by various accounts and reports, both domestic and foreign, regarding the importation of alcoholic beverages. Drinking was prevalent across all social classes. In a letter to his friend Eiríkur Magnússon in Cambridge in the spring of 1881, poet Steingrímur Thorsteinsson described the capital in a negative light, stating that he did not want to discuss much about the bourgeoisie lifestyle in the God-forsaken market town. Moral decay, cliques, a lack of identity, and excessive drinking were rampant. Despite being a frowned-upon concept, Thorsteinsson even expressed his desire for abstinence for the current generation.

Previously, only the upper class in Reykjavík would gather in exclusive clubs to drink and socialize. At the same time, commoners would purchase cheap spirits at the store counter. However, in 1857, a Danish man named Níels Jörgensen obtained a restaurant license in Reykjavík. He later bought a small house on the corner of Aðalstræti and Austurstræti, where Ingólfstorg now stands. Níels Jörgensen had arrived in Iceland with Count Trampe, the governor of Iceland, and served as his servant. He established a successful restaurant and hotel business, which marked the beginning of Hotel Iceland and the well-known Pigsty pub. The establishment was also known as Greifakráin (The Count Pub) or Jörgensen’s Pub, and people often referred to it as Uncle Jörundur’s.

This is How the Pigsty was Described

Ágúst Jósefsson, a printer who stayed at Hotel Iceland between 1888-1890, gave a detailed description of The Pigsty. It was an old one-story building on Austurstræti and along Aðalstræti, with an attic. The building was named Gildaskálinn, and a restaurant run by Jörgensen was located there. There were three rooms on the side of the building facing Aðalstræti, and the townspeople had given each of them a special name. The parlour on the south side was called Almenningur and had tables and benches. Visitors went there to converse and drink together. To the left of the entrance was a smaller parlour, which people called The Pigsty. The name was intended to insult the guests who came, not because the room was untidy. It was a kind of bar with a high chest-high table, where guests drank what they bought while standing.

Brennivín and other strong drinks were mainly served there, measured in shot glasses and tin measures. A corridor for the staff was along the tables inside, carrying refreshments to both rooms. Behind the corridor was a low cabinet for glasses and trays, and on top, there were four well-made and lacquered light oak kegs with black handles. Brass faucets were at the bottom of the barrels, and above them was painted the alcohol’s name that was in them: Brennivín, Cognac, Rum, Whiskey.

The Smell of Booze and Cigarette Smoke Made People Sick

The Pigsty was a popular bar, particularly at the end of the fishing season, with domestic and foreign fishermen and townspeople known for their heavy drinking. While some unusual guests frequented the bar, disturbances and fights were rare inside, as any trouble usually spilt out onto Aðalstræti.

The third parlour, known as The Cabin, was where captains and helmsmen of foreign ships often drank wine, hot toddy, and Old Carlsberg with the townspeople; they were usually well-behaved and cheerful.

According to contemporaneous sources, the Pigsty was far from cosy. The smell of beer and wine was overwhelming, and the addition of tobacco smoke made the experience of spending time there even more unpleasant. The drunken men would stumble around and even fall asleep at the tables, making it difficult to navigate the space.

The Pigsty Became Tee-Total

During the early 20th century, many people who abstained from alcohol began flocking to the Pigsty. Newspapers of the time often criticized the establishment and its open drinking holes. In 1902, as the city’s fishing fleet prepared for the winter season, the Pigsty was reportedly the busiest spot in town, serving up to five barrels of brennivín per day. However, protests against the establishment began, led by people from the temperance league. They would sit outside the Pigsty and encourage those heading inside to visit the YMCA instead. In 1906, 12 men from the Good Templar Lodge purchased Hotel Iceland, where the Pigsty was located, intending to run a restaurant that did not serve alcohol. This marked the end of Pigsty’s reign as a popular drinking spot.

For more information on The best Icelandic beer, Icelandic micro- and craft breweries as well as the best bars, check out our blogs: The Beers in Iceland, Craft Breweries in Iceland – Travel around the country, and Discover the Best Bars in Reykjavik.