In the annals of history, few figures have led as tumultuous and captivating a life as Jørgen Jørgensen (1780–1841). Born to Denmark’s royal watchmaker and commencing his nautical journey as a teenage sailor, Jørgensen’s adventurous spirit took him across continents. From the bustling docks of Copenhagen to the rugged coasts of Iceland, his tale is as unpredictable as the seas he sailed. Throughout his life, he transitioned from a mere sailor to an instrumental figure in Tasmania’s colonization and, most notably, to the audacious “Protector of All Iceland,” a title he conferred upon himself during his brief and controversial reign. This blog tells the story of the Dog Days King Jørgensen and how Iceland suddenly became independent for about two months in 1809.

Characters of Importance:

Jørgen Jørgensen: Son of the royal watchmaker of Denmark, his early years in Copenhagen were marked by brilliance and mischief. Starting as a mere sailor on British ships at the age of fourteen, Jørgensen’s journeys took him across continents – from South Africa to Australia, even playing a pivotal role in the British colonization of Tasmania. He swiftly climbed the ranks with dedication and talent, eventually earning the title of captain. After twelve transformative years at sea, Jørgensen returned to Denmark at 26. Though Danish by birth, his extended vacation with the English made him seem more like a Brit than a Dane.

Samuel Phelps: A soap maker of means. Made the expedition to Iceland possible.

Count Frederich Trampe: Governor of Iceland. He had been appointed Governor of the country in 1807 when Ólafur Stephensen was made to step down due to misusing funds (claims that were later retracted).

Captain Alexander Jones: British Navy Captain who restored order to Iceland.

Why “Dog Days King”? Jørgensen’s reign lasted roughly over the time “dog days” period. Estimates for the beginning of the dog days vary widely, ranging from 3 July to 15 August, and their duration can span from 30 to 61 days. Jørgensen’s reign lasted between June 26 and August 25, 1809.

The Danes, the British, and a New Beginning in London

In 1807, during Jørgensen’s stay in Denmark, war erupted between the Danes and the British. Despite his aversion to battling the British, Jørgensen found himself commanding a Danish military ship. His leadership only lasted three months in 1808 before he was defeated by a British warship and captured. As a captain, he was allowed to walk free based on his word of honour and settled in London. There, he met an Icelandic merchant named Bjarni Sívertsen, who told him about trade opportunities in Iceland. Due to the British capture of Icelandic and Danish merchant ships, no ship had gone to Iceland since the beginning of the war. This made it necessary to bring necessities to the citizens, and they could buy products such as tallow from them.

Jørgensen, having years of experience in colonial trade, became fascinated by the idea of a trading expedition to Iceland. He mentioned this to James Savignac, whom he met in a London restaurant. Savignac introduced him to a soap merchant named Samuel Phelps, who urgently needed tallow for soap making. This marked the beginning of the Icelandic adventure. Phelps chartered a ship loaded with necessities and sent Savignac to Iceland. Jörgensen was hired as an interpreter. The expedition departed and arrived in Iceland at the beginning of 1809.

Forced Trade in Iceland

Initially, they were refused a trading license as it was forbidden to trade with foreigners. However, they had a so-called „Viking license”, which allowed the capture of enemy ships during wartime. So they took a ship lying off the coast, and this was enough to force a trade agreement. The trade was slow as they had arrived mid-winter, and the buying season was not until summer. As March passed, it was decided to send Jörgensen back with an empty ship while Savignac would wait out the buying season.

Jørgensen returned to London in April and informed Phelps of the news. It was quickly decided to embark on another expedition in the summer. Phelps bought two ships and applied for the protection of the British fleet. Phelps agreed to go along himself and hired Jörgensen as an interpreter. The larger ship was loaded with necessities, and they headed for Iceland again.

At the same time, the Danish Governor, Frederik Trampe, returned to Iceland and renewed the trade ban with foreigners. Soon after, the British warship Rover arrived, as Phelps had requested, and forced the renewal of the trade agreement from the winter before. With that done, Rover sailed away and was gone when Phelps’ expedition arrived in Iceland a short time later. Governor Trampe, however, did not advertise the new trade agreement, and it did not appear that he intended to do so. After a three-day wait, Phelps and his companions made it ashore and arrested Trampe.

A Power Vacuum and the Emergence of a New Leader

With the Governor’s arrest, the nation was thrust into turmoil. This sudden power vacuum threatened the country’s stability and English commercial interests. Enter Jørgensen, who emerged as an unexpected leader. Despite his Danish origins, he swiftly declared Iceland’s independence from Denmark, stripping all Danes of their positions and assets. Under his rule, a revamped administrative board was introduced, with mandates that only domestic officials could serve the nation. He revived the ancient spirit of the Alþingi by calling for eight representatives appointed by the locals to form the parliament. There were sweeping economic reforms: debts owed to Danish merchants and the king were cancelled, taxes for the next year were halved, and grain prices were slashed. Jörgensen also championed societal improvements, including better healthcare, education, and an enhanced judicial process. No longer were Icelanders restricted in their movement; previously, travel within the country required a permit.

Jørgensen, the Protector of All Iceland

Under this new system, English merchants could profit and Jørgensen moved into the Governor’s House at Austurstræti 22. In these early days, though, chaos was rife. The people were initially fearful, prompting Jørgensen to ensure their safety. While he maintained that not all debts were cancelled, two men were still detained under his directive. Despite resistance and confusion, many Icelandic officials opted to serve under his new regime. His call for parliamentary representatives, however, went unanswered. By July 11, 1809, Jørgensen proclaimed his temporary leadership “until a regular national government is decided”, effectively crowning himself the “Protector of All Iceland”. Yet, he also vowed to step down the following summer when the Icelandic Parliament convened.

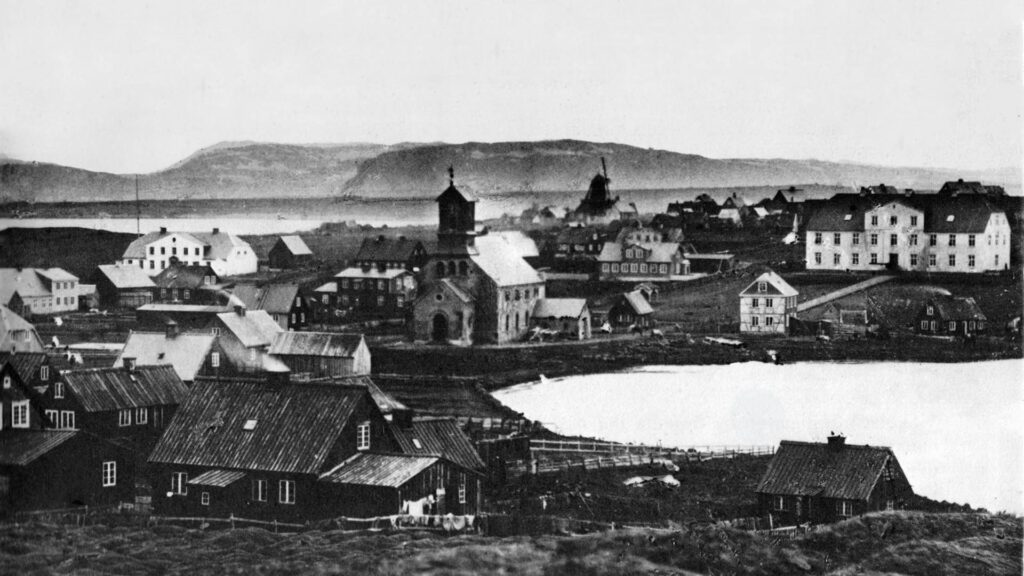

Jørgensen’s tenure saw the birth of a new Icelandic flag, blue with three white cod, proudly flying over Reykjavík. He journeyed north to seize the assets of Danish merchants and, upon his return, prioritized health and education reforms in Reykjavík. As weeks turned to months, Jörgensen’s presence became a memorable part of the city’s fabric. Clad in a captain’s attire, flanked by eight Icelandic bodyguards, he patrolled Reykjavík’s streets, symbolizing his unexpected but seemingly lasting authority

The Fall of Jørgensen and A Voyage Back

August 25 marked the end of an era as Jørgensen’s unexpected reign stopped. Upon the arrival of another British warship, Talbot, under the command of Captain Alexander Jones, it became clear that Jørgensen’s bold actions, including the unauthorized detention of Governor Trampe, would not go unchecked. The ‘Dog Days King’ audacity had raised many eyebrows and Captain Jones was set to rectify the situation.

Forced to leave Iceland, Count Trampe was placed aboard the ‘Margaret & Anne’. In contrast, Jørgensen found himself on the ‘Orion’, a ship that ironically belonged to Trampe. But a twist of fate saw the ‘Orion’s’ original crew, now prisoners, aboard the ‘Margaret & Anne’. Their dissatisfaction with their circumstances and provisions became palpable when they set the ship’s wool cargo aflame on the second day of the voyage. The captain could not manage the dire situation as the fire raged and chaos took hold.

The ‘Orion’ trailing behind finally caught up with the burning ‘Margaret & Anne’. Jørgensen, showcasing his leadership and expertise, took command of the dangerous situation. Although he couldn’t save the ship, he orchestrated the successful rescue of the entire crew, transferring them safely to the ‘Orion’. This extraordinary rescue feat earned Jørgensen some commendation.

With the crew saved, the ‘Orion’ returned to Reykjavík. There, in the port, another ship, the ‘Talbot’, still remained. Captain Jones had taken Governor Trampe and others aboard this warship, leaving Jørgensen, Phelps, and others on the ‘Orion’. The ‘Orion’ then set its course straight for London. The ‘Talbot’, however, would lag behind, arriving two weeks later.

A Hero’s Welcome Denied

Jørgensen’s return to Britain was far from the hero’s welcome he might have expected. The tumultuous Iceland adventure had concluded with Jørgensen heroically saving a ship’s crew. Still, that act was overshadowed by the charges and allegations awaiting him. Governor Trampe’s accusations weighed heavily against Jørgensen.

Upon reaching London, instead of accolades, Jørgensen faced confinement. Despite his efforts to recount his version of the Icelandic events through writings, the shadows of his actions loomed large. He was soon imprisoned and later sent into exile in Tasmania. He never returned to Denmark again.

When Jørgensen and Hooker visited Viðey Island

One of the prisoners of Margaret & Anne was an English botanist named Sir William Hooker. He had travelled with Jørgensen and Phelps to Iceland at the suggestion of his friend Sir Joseph Banks, naturalist and lover of Iceland.

The day after Jørgensen’s Proclamation of Iceland’s independence, he, Mr Phelps and Mr Hooker visited the former Governor Ólafur Stephensen in Viðey Island. While there, they had one of the biggest feasts ever recorded in Iceland. William Hooker wrote about the feast in his travelogue A Journal of a Tour in Iceland (1809), which gets more incredible the further you read – and undoubtedly invokes memories of the famous Monty Python restaurant scene in The Meaning of Life. Let’s give William Hooker the word:

We were immediately ushered through the entrance, where we were obliged to stoop at the doorway into a spacious hall with a large wooden staircase and, hence, through an extensive and lofty parlour into his bedroom, where I presented to him a letter of introduction, and a present of prints and books from Sir Joseph Banks, whose very name made him almost shed tears. …During our conversation, some rum and Norway biscuits were offered to us. We then took a little walk about the island, which is scarcely more than two miles in circumference and is one of the most fertile spots in Iceland, producing some of the best sheep, besides excellent cows, horses, peat, and good water….

We had scarcely reached the extremity of our walk when a servant came to announce that dinner was on the table. Consequently, though somewhat against our inclinations, we were obliged to return for the earliness of the hour, which was not more than half-past one. Our having already taken some refreshments had kept us from being very hungry.

We found the table set out in the large room… When we sat down to the table, a little interruption was caused by the breaking down of the chair upon which His Excellency had seated himself, but this was soon settled, as there, fortunately, was still a vacant one in the room to replace it… On the cloth were nothing but a plate, a knife and fork, a wine glass, and a bottle of claret for each guest, except that in the middle stood a large and handsome glass castor of sugar with a magnificent silver top.

The natives do not drink malt liquor or water, nor is it customary to eat salt with their meals. The dishes are brought in singly: our first was a large turenne of soup, which is a favourite addition to the dinners of the richer people and is made of sago, claret, and raisins, boiled to become almost a mucilage. We were helped to two soup plates full of this, which we ate without knowing if anything more was to come. No sooner, however, was the soup removed than two large salmon, boiled and cut in slices, were brought on, and, with them, melted butter, looking like oil, mixed with vinegar and pepper: this, likewise, was very good, and, when we had with some difficulty cleared our plates, we hoped we had finished our dinners.

Not so, for there was then introduced a Turenne full of the eggs of the Cree, or great tern, boiled hard, of which a dozen were put upon each of our plates; and, for sauce, we had a large basin of cream, mixed with sugar, in which were four spoons, so that we all ate out of the same bowl, placed in the middle of the table. We petitioned hard to be excused from eating the whole of the eggs upon our plates, but we petitioned in vain. “You are my guests,” said he, “and this is the first time you have done me the honour of a visit. Therefore, you must do as I would have you; when you see me in the future, you may do as you like.” In his own excuse, he pleaded his age for not following our example, to which we could not reply.

We devoured with difficulty our eggs and cream but had no sooner dismissed our plates than half a sheep, well roasted, came on with a mess of sorrel (Rumex acetosa), called by the Danes scurvygrass, boiled, meshed, and sweetened with sugar. It was to no purpose we assured our host that we had already eaten more than would do us good: he filled our plates with the mutton and sauce and made us get through it as well as we could, although any one of the dishes, of which we had before partaken, was sufficient for the dinner of a moderate man.

However, even this was not all; for a large dish of waffles, as they are here called, that is to say, a sort of pancake made of wheat flour, flat and roasted in a mould, which forms several squares on the top, succeeded the mutton. They were not more than half an inch thick and about the size of an octavo book. The Governor said he would be satisfied if we ate two of them, and, with these moderate terms, we were forced to comply. For bread, Norway biscuit and loaves made of rye were served up; for our drink, we had nothing but claret, of which we were all compelled to empty the bottle that stood by us, and this, too, out of tumblers, rather than wine glasses.

It is not the custom in this country to sit after dinner over the wine, but we had to drink just as much coffee as the Governor thought proper to give us. The coffee was undoubtedly delicious, and we trusted it would terminate the feast. But all was not yet over, for a huge bowl of rum punch was brought in and handed around in large glasses pretty freely, and to every glass, a toast was given.

If at any time we flagged in drinking, “Baron Banks” was always the signal for emptying our glasses so that we might have them filled with bumpers to drink to his health, a task that no Englishman ought to hesitate about complying with most gladly, though assuredly, if any exception might be made to such a rule, it would be in an instance like the present. We were threatened with still another bowl after we should have drained this, and accordingly, another actually came, which we were with difficulty allowed to refuse to empty entirely; nor could this be done, but by ordering our people to get the boat ready for our departure, when, having concluded this extraordinary feast by three cups of tea each, we took our leave and reached Reykjavik about ten o’clock; but did not for some time recover the effects of this most involuntary intemperance.

William Hooker: Journal of a Tour in Iceland in the Summer of 1809

Wow! What a feast! I don’t know how they ate all that and didn’t throw up 😮