The prison in Reykjavik was established on land from the royal estate of Arnarhóll, which was gifted to the institution. On March 20, 1759, the Danish king decreed the construction of a prison in Iceland, influenced by Skúli Magnússon, the first Icelandic treasurer. Skúli was alarmed by the increasing number of nomadic inhabitants, those without a permanent residence on any specific farm, often referred to as the “wandering plague.” In 1753, Skúli appealed to the king for funds to establish a correctional facility to house these “young and robust vagabonds roaming the nation in groups.”

To fund the prison’s construction and maintenance, a tax was imposed on properties and the value of cattle (known as the Prison Tax). This levy was not well-received by the populace.

Construction began in 1761, but due to various delays, it wasn’t completed until a decade later. Convicts, alongside Danish and Icelandic workers, contributed to the prison’s construction. Once the building was complete, the inmates began work, primarily benefitting the new cloth and garment factories, known as the New Enterprises, and other miscellaneous tasks in the emerging capital of Iceland. Under the administrative umbrella of the Danish monarchy, these prisoners were consistently labeled as slaves, equating their roles to that of enslaved workers. They played crucial roles in the burgeoning settlement’s myriad tasks.

Prison Fit for 70 Prisoners

The prison, covering an area of about 260 square meters, was crafted from hewn dolerite. It featured double-layered walls, a gabled timber roof, and small windows secured with iron bars. Upon entering, one would find a hallway with a staircase to the upper floor. The warden’s residence was on the right, and on the left, a spacious kitchen and the prison guard’s quarters. The back of the building contained two workspaces, one equipped for wool-working women, and another for repeat offenders. The upper floor housed four prison cells, with an attic above for wool and rope storage. Although designed to hold up to 16 major criminals and 54 regular inmates, it rarely hosted more than 40 prisoners at once. Both genders were incarcerated, and their interaction was so unrestricted that some children were even born within its walls.

Nonetheless, the prisoners’ living conditions were often dire, especially during harsh weather. The hardships following the 1783 Laki eruption took a toll, leading to inmate deaths from starvation and suffering. Conditions worsened post-1800, when the Napoleonic Wars and British strikes on Denmark disrupted shipments to Iceland, resulting in severe food shortages. This impacted the prison population heavily. By 1813, the Danish government’s financial collapse led to the penitentiary’s closure and the release of its remaining inmates. It was officially decommissioned three years later.

Arnes Pálsson: From Notorious Convict to Warden

In 1764, Arnes Pálsson, a notorious thief and bully from the West Fjords, was apprehended. His original sentence was a lifetime in prison, accompanied by flogging and a branding mark on his forehead. However, on April 11, 1766, a royal decree spared him from the branding.

By then, Arnes was approximately 47 years old, though his age, as listed in records, fluctuates, making him appear alternately younger or older.

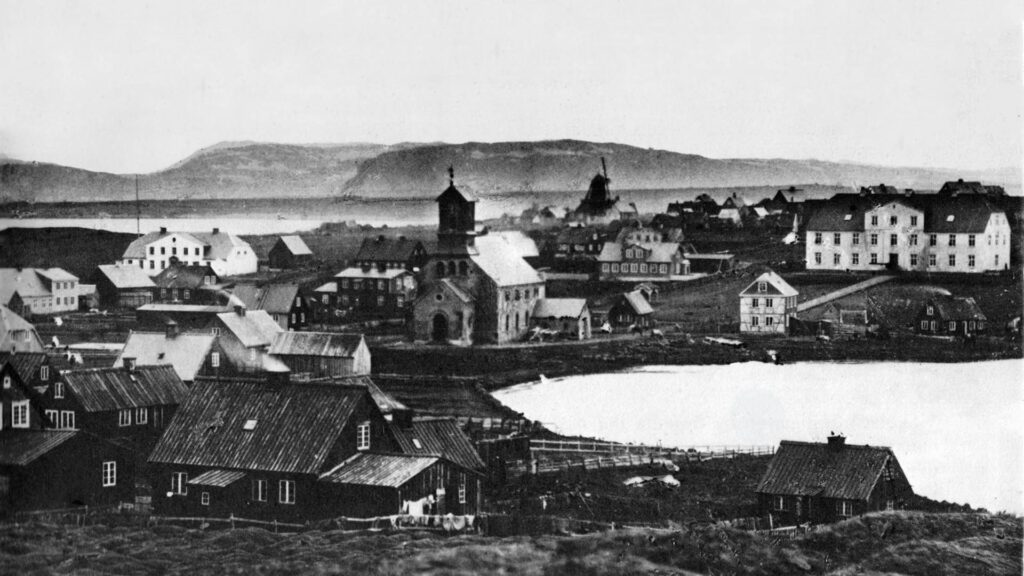

On July 2, 1766, Arnes was incarcerated at the Arnarhóll prison. Considering the landscape visible from the prison door during that era, one would notice stark differences compared to today. Reykjavik primarily clustered around Aðalstræti. This area housed the New Enterprises buildings, which included a weaving room, a lint-cutting room, and other associated facilities. Nearby, workers of the New Enterprises resided in modest huts. Close to Arnarhóll, near the Pond and the northern seaside, were a number of farms, smallholdings, and labourers’ homes. This area was known for its pervasive poverty and “debauchery,” giving Reykjavik its infamous reputation at the time.

Upon Arnes’s arrival to serve his sentence, the prison in Reykjavik was already under construction. Intriguingly, prisoners themselves were engaged in building it. Yet, the structure wouldn’t be completed for another five years.

Arnes Was Thought Too Mean to Stay in Iceland

A year after Arnes began his sentence, county commissioner Ólafur Stefánsson and attorney Björn Markússon formulated a charter for the prison in Reykjavik. In collaboration with the Bishop in Skálholt, they were appointed as the institution’s overseers. Recognizing the prison’s limitations in accommodating high-risk criminals, especially with the lack of demanding labor assignments, they presented a proposal to the mayor. They suggested transferring three particularly menacing prisoners to Copenhagen’s infamous Stokkhúsið. Among these was Arnes Pálsson, who was accused of instigating unrest, threatening to commit arson, and engaging in other perilous deeds. Though their proposal didn’t secure royal endorsement, it was later extensively revised. These documents offer the earliest detailed glimpses into Arnes’s incarceration.

Originally conceptualized as a workhouse, the prison struggled to provide indoor work to its inmates. This often led to them being sent outdoors for tasks such as mowing and rowing, activities that unfortunately came with reduced oversight.

By 1785, the institution saw the appointment of a special correctional officer, Brun. His tenure may have been short, lasting just over a year, but Brun’s reputation became one of infamy, marking him as one of Iceland’s most notorious prison wardens. Interestingly, he and Arnes forged a deep bond of friendship. Yet, this camaraderie did little to brighten the overall grim ambiance of the prison. The inmates’ days were punctuated by hunger, illness, and the omnipresent threat of indifferent guards.

The Notorious Prison Guard Brun

Brun, while married, was notoriously unfaithful. Legends abound of his advances towards many young women, often without their consent. One such tale tells of Brun impregnating an imprisoned girl and then cruelly ending her life before she could give birth.

The love story of two inmates – a man and a woman – was widely known inside the prison walls. The prison’s lax segregation meant relationships and childbearing among prisoners were not uncommon. Upon discovering their affair, Brun inflicted such a grievous wound upon the man that many believe he castrated the prisoner, who tragically died shortly after. Rumors whispered that Brun possibly intended the woman for himself.

Brun’s notorious tenure is said to have resulted in the deaths of sixty prisoners, though it remains unclear if these were direct or indirect actions. The true extent of his crimes might forever remain a mystery. Most infamously, Brun was rumored to have poisoned Steinunn at Sjöundá after impregnating her. However, this tale is implausible as Steinunn passed away in 1805, years after Brun’s own death. Such stories have been preserved through generations, evolving and intertwining with folklore.

Brun’s Mysterious End

Brun’s life concluded as mysteriously as the tales of his misdeeds. In 1787, merely two years after his employment commenced, Brun met his unexpected end. One fateful morning, he ventured into the fields of Arnarhóll, where he encountered an unfamiliar brown horse. As he attempted to shoo it away, the horse retaliated, landing a fatal kick to Brun’s chest. As quickly as it had appeared, the horse vanished, never to be seen again.

No one could recall ever having seen that horse before. Many speculated that the horse was an ethereal agent of vengeance summoned to deliver justice for Brun’s transgressions.

And Arnes Becomes a Prison Guard

Despite Brun’s villainous reputation, Arnes treated Brun with such respect that he was elevated above other prisoners. This behavior aligned with Arnes’s past reputation. Numerous accounts praised his demeanour; from the west coast farmers to the authorities he encountered, he was consistently described as behaving “piously and harmlessly,” showing genuine remorse for past mistakes.

In light of such commendations, Arnes was appointed the prison’s guard on April 1, 1786, being recognized as “the most loyal and suitable person available.” Aside from overseeing Christian education among the prisoners, his duties were exempted from other work. The once-notorious itinerant thief had now assumed an official role.

In spring 1787, after serving for 21 years, Arnes requested release. Yet, the power dynamics had shifted significantly. The inmates lodged a formal complaint against him for his brutal treatment, questioning whether someone with his past should have authority over them. The poignant letter ended with a plea for Pastor Guðmundur Þorgrímsson to intervene. However, the prisoners’ plea fell on deaf ears. Councilor Levetzow instructed Hinrik Scheel, now the prison director, to investigate and if the allegations proved true, to punish Arnes. The outcome remains nebulous, but Arnes retained his position.

By 1792, Arnes, nearing eighty and showing the wear of life’s travails, received his release from the prison in Reykjavik after 26 years. His subsequent years remained a mystery until 1797 when records showed him residing in Grjóta as a “decrepit” and “pauper” old man. By 1804, he was moved to Engey, where he eventually passed away on September 7, 1805. He was laid to rest in the old cemetery at Aðalstræti on September 11th.

Arndís Jónsdóttir’s Saga

By 1771, as the prison’s construction drew to a close and Arnes marked his fifth year of confinement, a new face appeared among the prisoners: Arndís Jónsdóttir. A young woman in her twenties, Arndís had been condemned to prison in Reykjavik for bearing three children with married men. Hailing from Eyrarbakki, her story had already garnered much attention — first, her exile from Skaftafell County after having two children, and later, a death sentence at Stokkseyrarþing for the birth of her third child. Fortunately, the latter sentence was commuted to four years of penal servitude.

A significant chapter in her tale unfolded on December 17, 1772, when she gave birth within the prison walls. Arndís named Arnes Pálsson, her fellow inmate, as the child’s father — a claim he readily accepted. However, when she birthed another child on August 8, 1774, and once again named Arnes as the father, he denied it. Notably, despite the prevailing severity of criminal penalties at the time, such incidents did not amplify the prisoners’ punishments.

Arndís Found Marital Bliss

By 1775, Arndís’s prison term came to an end. Yet, her challenges persisted. Upon her return to Eyrarbakki and while residing with her parents, she gave birth to a sixth child, this time alleging that a prison guard was the father. This event initiated more legal proceedings. Eventually, Arndís faced another sentence, this time to the infamous Spindehuset, a female prison in Copenhagen. A twist of fate intervened: a widower proposed marriage to her, and in light of this, the king decreed her exemption from punishment. Although her would-be husband passed away before their wedding, Arndís soon found marital bliss with another.

Arndís Jónsdóttir’s tumultuous journey serves as a vivid illustration of the period’s legal procedures. Professor Gudni Jonsson commented, “Her case was scrutinized by a multitude, ranging from local commissioners and bailiffs to the king himself. Such an assemblage of dignitaries, all because a woman dared to heed one of humanity’s most primal urges outside the bonds of matrimony — and bore the entirety of society’s blame.”

From Prison to the Governor‘s House

Since 1683, the role of the Governor had been paramount in Iceland, with young Danish nobles frequently appointed to the position. Historically, this assignment was viewed as an initiation, the first step on their career path, because residing in Iceland was often deemed unsuitable for the nobility.

In 1819, Ludvig Moltke, a 29-year-old from a distinguished noble lineage, became the Governor of Iceland. The prior governors had made their homes in modest wooden house, which has the address Austurstræti 22 today. However, this dwelling seemed inadequate for Moltke and his wife, Reinholdine Frederikke Vilhelmine, given his stature and office. They perceived potential in an abandoned prison, envisioning it as a fitting official residence. With approval from the Copenhagen government, Moltke embarked on extensive renovations during the winter of 1819-1820, transforming it thoroughly. This building was later known as the Governor’s House, sometimes called the King’s Garden. Yet, by 1824, Count Moltke and his wife had departed from Iceland.

Lorentz A. Krieger: A Visionary Administrator

Ten years after Moltke’s appointment in 1829, Iceland welcomed Lorentz A. Krieger as its new governor. At 32 and single, Krieger was energetic and impactful, especially in Reykjavik. He championed structural reforms, initiated the election of a building committee, and even personally financed the reconstruction of the School Cairn. Under his leadership, construction was prohibited in specific areas, and he pioneered the Lækjargata road.

By 1835, Krieger was representing Iceland in the Danish assembly, where he boldly introduced proposals for Iceland to attain home rule. Remarkably, such progressive ideas came from a Dane, a fact often overlooked in Icelandic narratives.

During Krieger’s term, Prince Frederick Christian of Denmark, later known as Fredrik VII, visited Iceland. Banished due to his wayward behavior and marital discord, the prince nonetheless embraced his Icelandic sojourn. He frequently enjoyed festivities at the King’s Garden in Lækjartorg, often in the company of Krieger.

However, Krieger’s tenure in Iceland was relatively brief. He resigned as Governor in 1836, taking up a similar role in Aaleborg. Tragically, he passed away soon after, aged just over forty.

After that, the house was the home of Iceland‘s Governor until 1904, when Iceland finally got home rule. Then it was changed to the Government Office, and it has kept that role ever since.