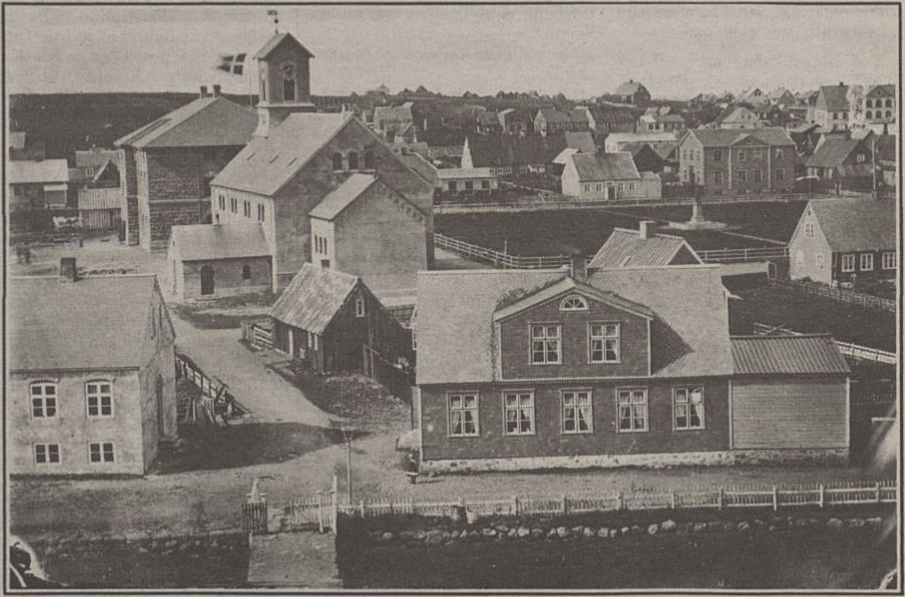

Downtown Reykjavik holds a treasure trove of old houses, each echoing the city’s rich history. Beyond their vibrant exteriors and distinct designs, these buildings have witnessed generations of change. Despite the many old houses, many historical buildings have also disappeared through the decades, many due to an infamous detailed land use plan, which was never fully realized. This blog will guide you through these historical landmarks, shedding light on their stories and architectural significance. Join us in exploring Reykjavík’s timeless charm.

Góðtemplarahúsið í Reykjavík: From Historic Landmark to Demolition

Góðtemplarahúsið í Reykjavík, commonly known as Gúttó, stood as a testament to history on the shores of The Pond. This one-story, corrugated iron-clad wooden structure was uniquely positioned south of the Parliamentary house, nestled at the junction of Templarasund and Vonarstræti.

Constructed by the Good Templar Lodge of Reykjavík, the edifice was inaugurated on October 2, 1887. By 1890, it proudly showcased a box stage, becoming a hub for theatrical performances until 1897 when the Reykjavik Theatrical Company shifted its operations to Iðnó. Over the years, it housed various associations, with some using the space for extended periods. Notably, from 1903 onwards, it became the official meeting place for Reykjavík’s municipal council, which previously convened at the Penitentiary on Skólavörðustígur. This location’s significance is further etched in history, as it witnessed the tumultuous Gúttó fight on November 9, 1932, during a town council meeting.

Although the Icelandic government took ownership in 1935, the Templars and several non-profit organizations continued their activities there. Sadly, in 1968, Guttó was razed, making way for a parking lot serving members of parliament.

The Gúttó fight

On November 9, 1932, downtown Reykjavik witnessed the Gúttó clash—a turbulent street riot. During a town council meeting at Góðtemplarahúsið í Reykjavík, amidst the escalating effects of the Great Depression and surging unemployment, a proposal to cut public relief work was introduced. This suggestion sparked intense opposition from the public. A sizable crowd gathered at Gúttó, with protests first igniting within the building before they spilled onto the streets. The confrontations between police officers and workers intensified, culminating in the police’s retreat and the ultimate abandonment of the contentious proposal.”

A bystander described a portion of the fight as such:

“I came from the north of Pósthússtræti, having just passed by Hótel Borg. As I proceeded, I saw a multitude of people coming from the south of Templarasund, advancing northward with loud shouts between the Parliamentary Building and the Cathedral. They passed the monuments of Bishop Vídalín and Hallgrímur Pétursson. Among the crowd, 2-3 police officers seemed to be fleeing, not leading. One of them was Senior Police Officer Erlingur Pálsson. Another officer had made his way to the gates at Austurvöllur; he knelt there, seemingly overcome by wounds and gasping for breath. Above him towered a man with a large rafter, poised to strike the downed officer. The pressure from the crowd was so intense that I was pushed back, losing sight of the scene. Moments later, standing in front of Doctor Ólaf Þorsteinsson’s house, I saw Erlingur Pálsson and another policeman named Stefán assisting their wounded comrade, likely unconscious, to the doctor’s door. Roughly two minutes afterward, a bloodied Erlingur emerged, urging his also blood-covered companion to follow. Together, they plunged back into the chaotic fray.”

Out of the town’s 28 police officers, 20 participated in the fight, all of whom, including Police Chief Hermann Jónasson, were injured. Fifteen officers sustained head injuries, and it’s remarkable that many survived, given the severity of the confrontation. Three policemen were so severely beaten they never healed properly and had to quit the police force.

Lækjargata 8 – A House Fit for the Director of Health

Built in 1870 by Dr Jónas Jónassen, who would later become the Director of Health, this house in downtown Reykjavik showcased several construction innovations of its time. It boasted a spacious garret that extended throughout the home and had an unusually high ceiling. The house’s size was impressive for its era, and it broke from tradition by featuring its entrance on the building’s gable. This meant the room layout no longer revolved symmetrically around a front entrance, a custom typical for wooden houses of that period.

The design hinted at the Swiss chalet style, which was becoming increasingly popular in Norway. While the house showcased several characteristics of this style, it wasn’t a pure embodiment of the Swiss chalet design, making it a unique architectural specimen in the country.

By 1883, slate cladding adorned the east side and the south gable. A 1917 renovation introduced corrugated iron cladding and a tiled roof. An entry shed was originally positioned on the west side, with an additional shed housing stables, hen houses, and hay storage on the property’s western edge. This stable underwent a transformation in 1937, repurposed as a meeting and entertainment space. The entrance shed was removed in 1946. Fast forward to 1996: the older sheds were demolished, and a modern extension took their place on the original site.

A few years ago, the whole house was renovated to look like it did in the beginning.

Jónas Jónassen (1840-1910): A Pillar of Icelandic Medicine and Public Service

Jónas Jónassen, born in Reykjavík on August 18, 1840, became one of Iceland’s preeminent figures in medicine and public service. Son of the High Chief Justice and prefect, Þórður Jónassen, and his wife, Dorothea Sophia Lynge, Jónas’s path to greatness began early. After matriculating from The Learned School in 1860, he acquired his medical degree from the University of Copenhagen in 1866.

In the subsequent years, Jónas rapidly climbed the medical hierarchy. After briefly deputizing for Jón Hjaltalín in 1867, he assumed roles as an assistant in medical education and county physician. By 1873, he was the district doctor for the Reykjavík region, a post he held until 1895.

Jónas’s rise wasn’t without challenges. Despite being a favorite to succeed the aging Jón Hjaltalín in 1881, he was bypassed in favor of the Danish Hans Jacob George Schierbeck, a decision that stirred factionalism and disagreements. However, his commitment and reputation prevailed. He eventually succeeded Schierbeck as the Director of Health in 1895, serving until 1906.

Outside of medicine, Jónas was a dedicated public servant. Elected to the Reykjavík parliament in 1886, he served until 1892 and was later appointed as the king’s chosen member from 1899-1905. Furthermore, he was integral to Reykjavík’s town council from 1888-1900. As a scholar, he contributed various publications, notably the ‘Book of Medicine for the People’ in 1884.

Jónas married Þórunn Pétursdóttir Havstein (1850-1922), and together they had a daughter, Soffía Jónassen Claessen (1873-1943).

Austurstræti 19 – Reykjavik District Court

At Lækjartorg stands a distinct building: the bottom half, built in 1904, is crafted from hewn stone, while the 1962 top addition contrasts starkly in style. Many consider these modifications, along with the Landsbanki extension nearby, among downtown Reykjavik’s least appealing architectural decisions.

The original house on this site, constructed in 1818, belonged to Hafnarstræti 18. By 1901, the YMCA owned and utilized the building. However, they sold the southern part to Íslandsbanki Bank in 1904, who then constructed their bank there with grey stone exteriors and brick interiors. The 1940 restoration brought significant changes, including a concrete extension to the north with a pitched roof and a three-level staircase. The bank shifted its entrance in 1937 from the south to the east side.

Fast forward to 1962, four more floors were added atop the bank, and a new western extension replaced the old Kolasund. This new structure, completed in 1966, featured recessed roofing and wooden sides. Reykjavík District Court took over the space in 1992.

Lækjartorg in front of the house is one of Reykjavik’s oldest squares.

Lækjartorg Square in Downtown Reykjavik

During the early 19th century, a vision emerged to create an open space west of the Lækur, facing the Government Offices. Over time, this square took shape, framed by residences on Austurstræti and Hafnarstræti. By 1848, it proudly bore the name Lækjartorg Square. Throughout that century, it was a familiar sight to see rural folks pitching tents at Lækjartorg and Austurvöllur.

Lækjartorg Square in downtown Reykjavik was the people’s main gathering spot for generations. It hosted innumerable meetings that touched upon both the spiritual and material aspects of life. A landmark protest in November 1909 saw residents gather to oppose the removal of Tryggvi Gunnarsson from his role at Landsbanki. For decades, the Salvation Army convened meetings here, with passionate preachers spreading their message. The square was also a staple for the May 1 labour movement assemblies. A women’s gathering on October 24, 1975, set a record, becoming Reykjavík’s most attended meeting. However, with the Reykjavik District Court’s 1992 relocation to the square, public assemblies ceased.

For years, the square also stood as the nerve center of Strætó, Reykjavik’s public transportation, surrounded by bus stops. Before the king’s 1907 visit, an octagonal kiosk was erected in Lækjartorg. Though it moved multiple times — from Hverfisgata and Kalkofnsvegur in 1918 to the Árbær Open Air Museum in 1973 — it returned downtown. It meandered for a while until 2010, when it reclaimed its original spot in downtown Reykjavik on the square.

Austurstræti 22: Legacy of the Internal Legal Court

In 1801, the newly appointed judge of the Internal Legal Court, Ísleifur Einarsson, erected a house on Austurstræti in downtown Reykjavik. This structure, which still stands, is considered Austurstræti’s first direct construction. Shortly after its completion, Ísleifur sold it to Count Trampe and the Governor of Iceland. From 1805 to 1820, it served multiple purposes: the governor’s residence, his office, and an apartment.

In 1809, a significant shift occurred in the house’s history when Jörgen Jörgensen, an ambitious figure, took control of Iceland. Making the residence his stronghold, he detained the sitting governor and declared himself as Iceland’s sovereign ruler, claiming dominion over both its lands and seas. His reign was extremely short-lived—just about two months from June to August, which coincides with the “dog days” of summer, hence the nickname “Dog Days King” (in Icelandic, “Jörgen the Dog-Days King” or “Jörundur hundadagakonungur”).

The residence changed hands again when the governor relocated. The government bought it, and the Internal Legal Court utilized part of it. Its west wing housed the courtroom, while the east was reserved for town council meetings. The ground floor provided living quarters for a police officer, and another lived upstairs. This upper area, known as the ‘Black Hole’ by 1828, was a makeshift prison, mostly for intoxicated people.

This house witnessed unique events, like Police Sergeant H. Hendrichsen, who would occasionally transform the courtroom into a dance hall, personally serenading guests with his flute — not always sober. His antics likely led to his 1855 retirement, yet his colorful tenure remained legendary.

By 1873, the Internal Legal Court moved to the Prison on Skólavörðustígur, replaced by a seminary that remained until the University of Iceland’s 1911 establishment in the Parliamentary building. The edifice later morphed into shops and eateries. Unfortunately, a 2007 fire significantly damaged it. Although the owners initially proposed a high-rise in its place, public outcry prompted its reconstruction in its authentic design, preserving the few wooden pieces that survived the flames.

The Proposed Downtown Reykjavik Expressway

From 1962 to 1983, Reykjavik considered a land use plan that proposed an expressway right through the heart of the city, which would have led to the demolition of several historic buildings. This expressway was planned to stretch from Kalkofnsvegur, close to the present-day Harpa Concert House, reaching up to Norðurstígur, close to the Sea Baron, where it would intersect with another route running through Grjótaþorpið. The design visualized a four-lane road, with two lanes in each direction, planned to be elevated over the Customs House.

The path of this proposed expressway would have taken it past numerous city landmarks, including the Old Cemetery, the National Museum, and the University of Iceland, extending all the way to the seafront. An observant eye can see evidence of this plan on Suðurgata, which is flanked by the National Museum and the University of Iceland. The route was also designed to pass by the Parliamentary building and Reykjavik Junior College before culminating at Grettisgata.

Thankfully, this plan was not fully realized. Still, evidence remains: segments of streets raised above the Customs Building, and vacant spots where historic houses once stood, hinting at the blueprint that was to be.

Prominent among the lost structures was Uppsalir, located at Túngata and Aðalstræti’s junction. The first milk store in Reykjavik was housed in the basement. Its space became a parking lot for years, but today it’s the site of the Settlement Exhibition and a hotel. The Governor’s House, or Amtmannshúsið, was also razed, replaced by a parking spot on Ingólfsstræti. It took years for some of these gaps in the cityscape to be filled again, like the one on Tryggvagata, which remained a parking lot until a new building was constructed recently.

On the brighter side, many structures were saved or relocated. Dillon’s House, originally found at Túngata and Suðurgata’s corner, and Hansen‘s House on Pósthússtræti were moved to Árbær Open Air Museum. Key structures like the Prison on Skólavörðustígur and Reykjavik’s oldest house on Aðalstræti 16 were preserved.

The initial plan also marked the structures on Bernhöftstorfan and Tjarnargatan for demolition. While these quaint Icelandic timber houses were ageing, they represented a rich pre-independence history. To a post-independence generation, these houses became symbols of Icelandic heritage. Their passion led to many of these houses being saved. Around ten years ago, laws were even updated to ensure automatic protection for houses over a century old.

The Controversy Surrounding the Expressway

The expressway proposal was reflective of a global mid-20th-century trend to redesign cities around the automobile. This approach in downtown Reykjavik meant risking the city’s historic architecture for modern traffic demands. The public was divided: while some championed the benefits of modern infrastructure, many clamored to protect Reykjavik’s rich heritage.

By the 1980s, global urban planning trends shifted towards pedestrian zones and heritage conservation. Responding to these evolving perspectives, Reykjavik’s city council reviewed and eventually shelved the expressway proposal. Despite the loss of some historic buildings in the process, many were spared, allowing downtown Reykjavik to maintain its distinctive historical identity.