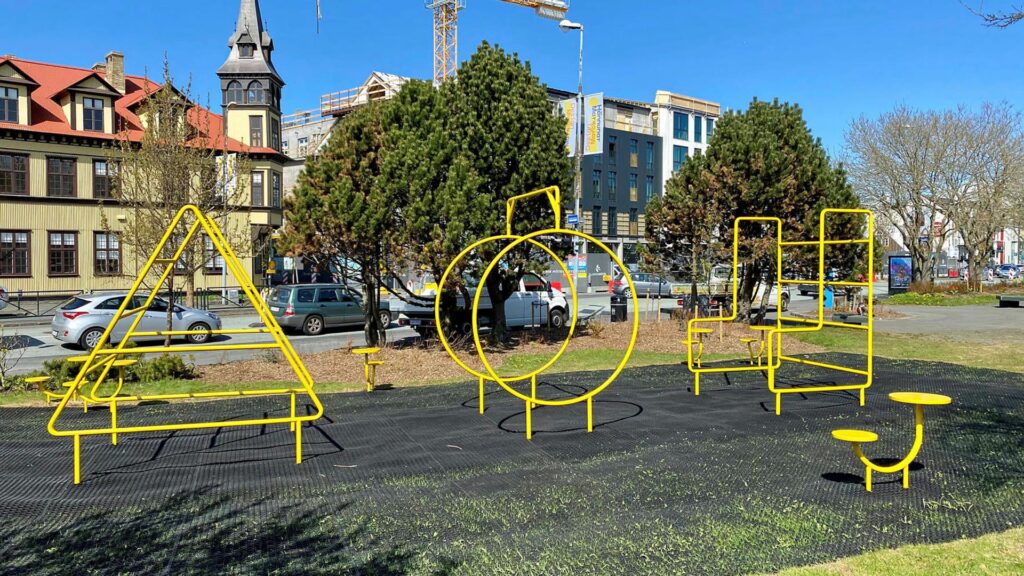

Around Reykjavik, you will find cultural signs telling you titbits about the history of the place. They mark historical monuments and areas within Reykjavik’s city limits. They are there to make the experience of the city’s residents and visitors more enjoyable and provide information about the capital’s history.

The Reykjavik City Museum manages the 62 signs.

Walking between those cultural signs in downtown Reykjavik makes a good walking tour.

Ingólfsnaust

From Ingólfstorg, walk towards the ocean. On the corner of Aðalstræti and Vesturgata, you will find a sign on Ingólfsnaust.

From the dawn of Icelandic history, the farmers of Reykjavik beached their fishing boats in Grófin. The ocean reached just about where you stand until the beginning of the 20th century. Their path from the farmstead to the sea is now Aðalstræti, Iceland’s oldest street and the home of The Settlement Museum. The museum shows ruins of a Viking hut since the 10th century and other artifacts found from the beginning of settlement in Reykjavik.

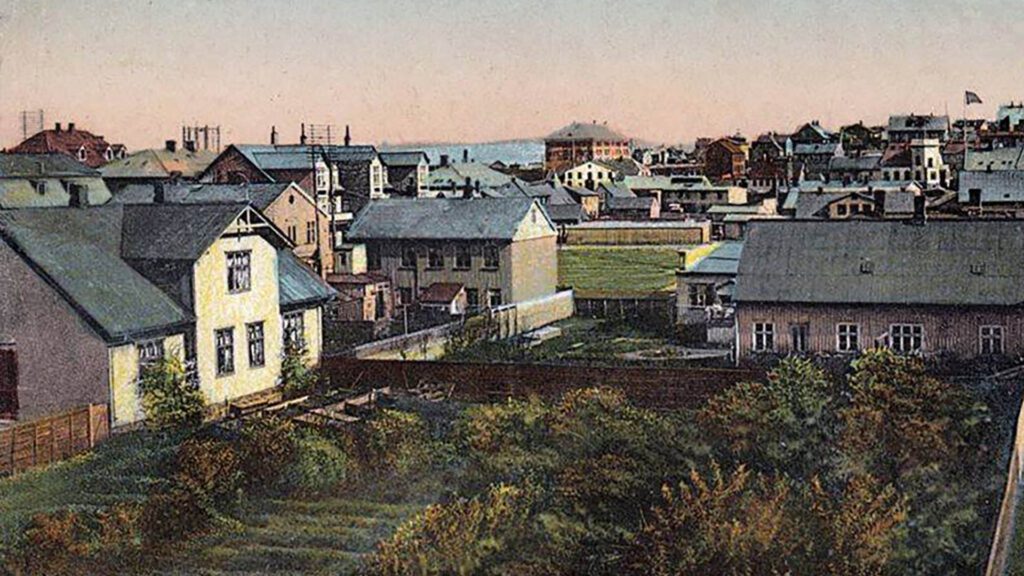

Trade began in Reykjavik in 1779-1780, when the company that traded under a monopoly license from the Danish and Icelandic King moved its premises from Örfirisey (Grandi) to Aðalstræti 2. However, the trade monopoly was finally abolished in 1786, and Reykjavik was granted its trading charter and five other communities around the country.

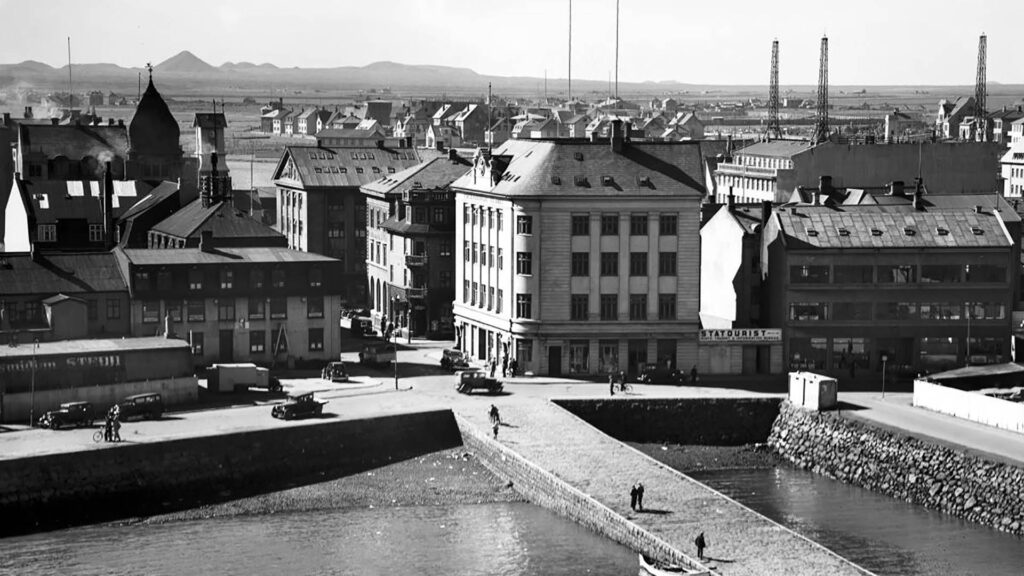

Despite abolishing the monopoly, the Danes dominated commerce in Iceland until 1855, when Free Trade was introduced. At that time, merchants set up shops along the shoreline north of Hafnarstræti and built jetties where their goods were loaded and unloaded from ships anchored in the bay. Reykjavik didn’t get a proper harbor until 1917.

The house at Aðalstræti 2 was built in 1855 by merchant Robert Tærgesen but was purchased in 1865 by another merchant Waldemar Fischer after whom Fischersund alley is named.

Gröndal’s House

Talking about Fischersund, take a stroll up the small alley. On your right-hand side, you will see a small red-timbered house.

The house is called Gröndal’s House, but famous Icelandic author, artist, translator, and natural scientist Benedikt Gröndal lived there. When he was alive, the house stood on Vesturgata, a couple of hundred meters up the next street. It was moved to its current location when its plot was redeveloped a few years ago.

Gröndal lived in the house for the last 20 years of his life. He bought it in 1888 and died in 1907. Gröndal was a larger-than-life character, and people who know his history can tell endless stories about his shenanigans. He, for example, is said to have sold the Northern Lights to a foreign investor – no one knows if it is true. Still, he was known as a great and inventive salesman so it could have happened.

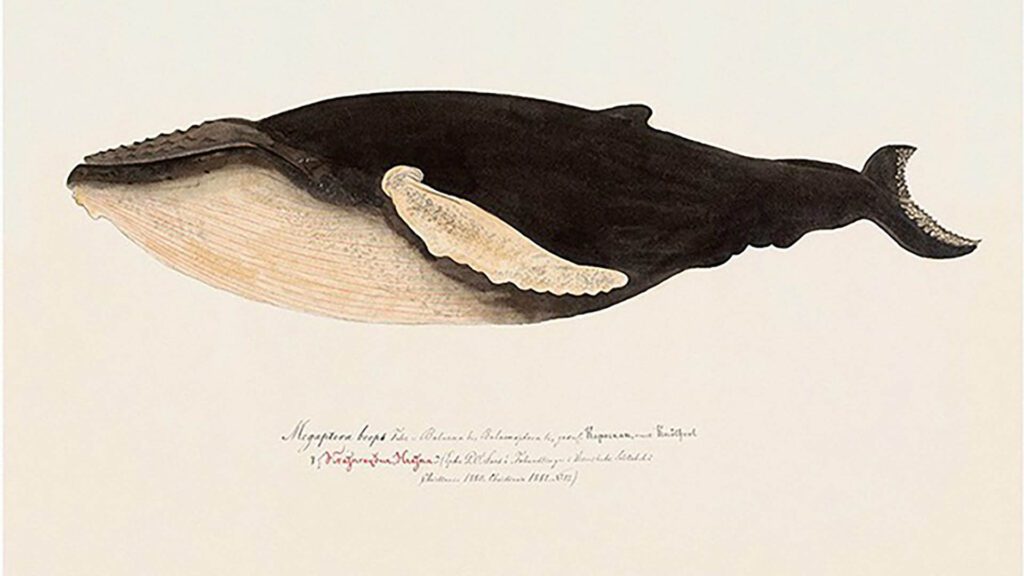

He translated works by Greek author Homer from Greek to Icelandic, published books on Icelandic animals with his drawings, and was one of the founders of the Icelandic Natural History Society.

There are posters for sale in many of Iceland’s stores with drawings of Icelandic animals, many of which were drawn by Gröndal.

Women’s House Hallveig’s Place

Go up the alley, cross the street next to Gröndal’s House and go on up. When you’re on the next road, Garðastræti, turn left. On the corner of Garðastræti and Túngata is a large house called Kvennaheimilið Hallveigarstaðir, which houses the Canadian and Faroe Island embassies, among other things.

The name translates as the Women’s House Hallveig’s Place. It is the only house that the Icelandic Women’s Movement owns. It is named after Hallveig Fróðadóttir, wife of Ingólfur Arnarson, and thus supposedly the first female settler of Iceland.

Hallveigarstaðir was built to house the activities of women’s groups in Iceland and to support their cultural and humanitarian work. The dream of a women’s center arose soon after Icelandic women gained the right to vote in 1915. Many women’s associations of that time were active in the Reykjavik area. Working on social welfare issues and an urgent need for facilities where they could work and hold meetings arose.

In 1919, Laufey Vilhjálmsdóttir delivered an address urging women to join forces to build a women’s center. In the following decades, women raised funds to make the house, and a joint-stock company was founded. Women and women’s associations were invited to buy shares which they did, and were able to fund the construction. The ground-breaking ceremony was held in 1954, and Hallveigarstaðir finally opened on June 19, 1967, on Women’s Rights Day.

The house is owned by the Federation of Women’s Societies in Reykjavik, the Federation of Icelandic Women’s Societies, and the Icelandic Women’s Rights Association.

The Grandmother of Grjótaþorp

Now you have to backtrack and turn right down the small street called Grjótagata. By Grjótagata 12 is a sign about Laufey Jakobsdóttir, the grandmother of Grjótaþorp”. She lived there between 1975 and 1995. She was born on September 25, 1915, in Borgafjörður and was married to Magnús B. Finnbogason (1911-1993), a master builder, writer, and inventor. They had eight children and many descendants.

She was passionate about social issues and was one of the founders of the feminist Women’s Alliance. Additionally, she was an honorary member of the animal protection association and an advocate for elderly care. She was also interested in preserving historic buildings and served as a chair of the architectural conservation group Torfusamtökin for a while.

She was renowned for her work with young people in the city center, for which she became known as the grandmother of Grjótaþorp. One of her achievements was to have a public toilet open in Grjótaþorp, where she worked long hours into the night, unpaid, to ensure youngsters had a safe haven.

Grjótaþorpið

A few meters down the street is another sign about the small neighborhood you are in, the Grjótaþorp or Grjóti Village. The name is derived from the house Grjóti, one of eight smallholdings on the estate of Reykjavik in the 18th century. The farmstead stood on Grjótabrekka at the top of Grjótagata.

When wood houses were being built in Aðalstræti in the latter half of the 18th century, a cluster of turf houses was built on the Grjóti property. The turf houses were the homes of landless laborers, fishermen, and staff of the Innréttingar (the New Enterprises, woolen production on an industrial scale intended to propel Iceland into the modern age).

The area was named Grjóti (Rock) after the rocky fields that stretched down the hill toward downtown Reykjavík. The rocks were cleared from the grass field in 1790 and used to build the Reykjavik Cathedral. Soon after that, inhabitants started making gardens on the land. No turf houses were left by the turn of the 20th century.

The Sheriff’s Garden and Víkur Church

Walk down the street and enter the small square in front of you. There are four culture signs in that small square.

The square is one of the oldest parts of Reykjavik and was the home to Víkurkirkja Church, probably the first church in Iceland. It was used until Reykjavik Cathedral was built next to Austurvöllur in the 18th century.

The oldest settlement in Reykjavik was between the Pond and the ocean. It is believed the first houses rose in the latter part of the 9th century by Aðalstræti. Many important relics from the settlement area have been excavated there. One of them is a piece of a wall from 871 ± 2 and a longhouse from the Viking age, which you can see in the Settlement Exhibition.

The first settlers came from Norway and the British Isles, and the excavated sites around Aðalstræti give a good impression of the community in the 9th and 10th centuries. People lived in longhouses, a type of wood-and-turf homes that were common in Scandinavia then. Nearby were smithies where people worked iron. Iron ore was acquired from bog iron nearby. Unearthed animal bones show that settlers caught birds and fish for food, practiced agriculture, and kept cattle and pigs.

The Location of Víkurkirkja

Víkurkirkja Church was built before 1200. Chieftains, descendants from Ingólfur Arnarson, lived in the area. His great-grandson Þormóður was the High Priest of the Old Norse religion when Iceland adopted Christianity around 1000. After the change of religion, farmers and chieftains started building churches on their estates. They had been promised they would be allocated as many places for souls in heaven as could be accommodated in their churches.

The square has been called the Fógetagarður or The Sheriff’s Garden since the late 19th century. A house stood by the edge of the square, sold to the town sheriff in 1893, along with the right to garden in the old churchyard. The sheriff’s wife took great care of the garden in the following decades. At that time, the old churchyard became known as the Sherrif’s Garden, and the name stuck. The large tree next to Skúli Bar (named after Skúli Magnússon) is one of Reykjavik’s oldest trees.

The statue in the middle of the square is of Skúli Magnússon, known as the Father of Reykjavik. He was the founder of the Innréttingar or the New Enterprises. As a result of the company, Reykjavik grew into a village, then a town, and lastly, a city and the capital of Iceland. One of the buildings of the New Enterprises still stands, Aðalstræti 10, which now houses Reykjavik… and the story continues, a part of the Reykjavik City Museum.

Author Theódóra Thoroddsen

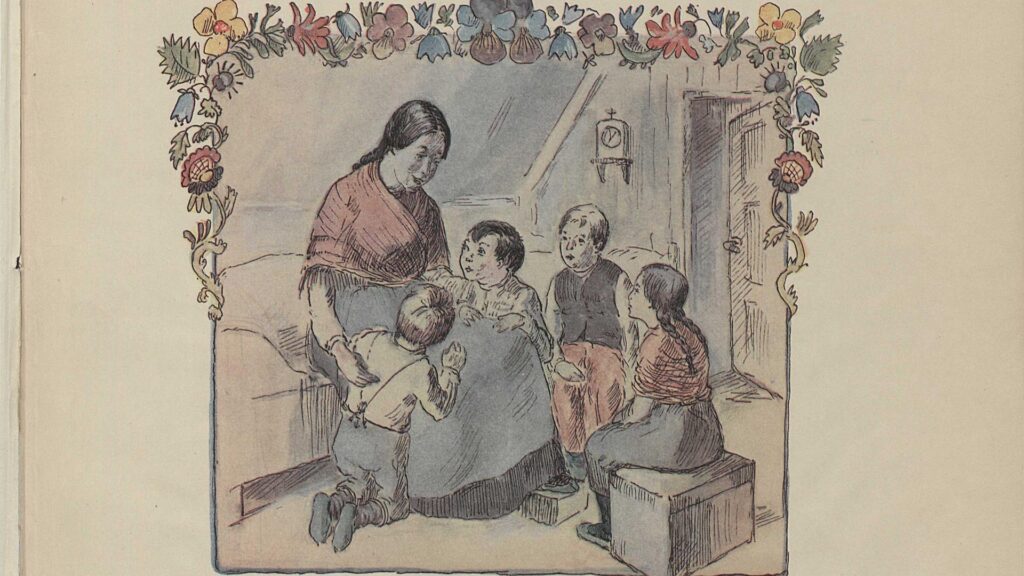

On the corner of Kirkjustræti and Tjarnargata, just by the square, is a sign about Theódóra Thoroddsen (1863-1954). She was a poet but is mainly known for her nursery rhymes, first published in 1916 and illustrated by Muggur, one of Iceland’s most famous illustrators. His most famous book is the Story of Dimmalimm.

First Women in Town Council and Parliament

Walk to the next intersection, where Reykjavik City Hall stands. Turn left and walk towards the next street on your left, called Templarasund. Next to the Parliament Garden is a sign on the Rights for Women and especially Bríet Bjarnhéðisndóttir, one of the first women in the City Council, and Ingibjörg H. Bjarnason, the first female Member of Parliament.

The Women’s Rights movement in Iceland began in earnest on December 30, 1887, when Bríet Bjarnhéðinsdóttir stepped onto the stage at Gúttó, the main meeting venue in Reykjavik at the time, and delivered a speech called “A lecture on the conditions and rights of women.” Gúttó stood where there is now a parking lot, on the corner of Templarasund and Vonarstræti. It was demolished in 1968.

Bríet Establishes the Women’s Paper

She founded a monthly periodical, Kvennablaðið (The Women’s Paper), published between 1895 and 1926. It was one of the leading publications promoting reform and women’s rights. The Icelandic Women’s Rights Association was founded in 1907 on Bríet’s initiative. And when women were granted the right to vote in Reykjavik council elections in 1908, it was decided to put forward a special women’s list. Bríet was on the list of candidates and was elected along with three other candidates.

Ingibjörg was Iceland’s first qualified gymnastics teacher and began teaching at the Reykjavik Girl’s College in 1903. She was the school’s principal between 1906 and her death in 1941. She was the first woman elected to Iceland’s Parliament in 1922 and represented the Women’s List until 1930. Ingibjörg was an especially vocal advocate for building Landspítalinn, a hospital to serve all Icelanders. Women raised funds for its building to commemorate the women’s franchise in 1915.

A statue of Ingibjörg was unveiled outside the Parliament in 2015, on the 100th anniversary of Women’s Right to Vote. It was the first whole sculpture of a particular woman in Reykjavik.

The Mother’s Garden

Turn back towards the Pond, and when you reach Vonarstræti, turn left. Cross Lækjargata and enter the small park there. It is called the Mother’s Garden. The garden opened in 1925 and was primarily intended for mothers with children. It had previously been a patch of uncultivated lands.

A statue called Motherly Love by Nína Sæmundsson was installed in 1930. It was the first sculpture by a woman to be erected in Reykjavik and the first public sculpture that was not a memorial or a portrait. You can read about Nína in our Reykjavik Artwork Walk Around the Pond.

Bernhöft’s Sward

Walk towards the ocean, down Lækjargata. You will see a small park at the corner of Bankastræti and Laugavegur shopping street. There is a sign about Bernhöftstorfan, the houses at the edge of the garden.

The name, Bernhöft’s Sward is derived from the T.D. Bernhöft bakery stood in Bankastræti 2 (there’s another bakery there now). The house was built in 1834 and housed the first bakery in Iceland. It was in business until 1931. Bernhöft cultivated the garden below the house and installed a water pump which was much used. The house is almost unchanged from when it was built.

In the 1970s, there were plans to demolish the whole row of houses to make room for a huge government office building. But due to fierce protests among young people, especially the conservation group Torfusamtök, the government decided against it, and the houses were finally protected.

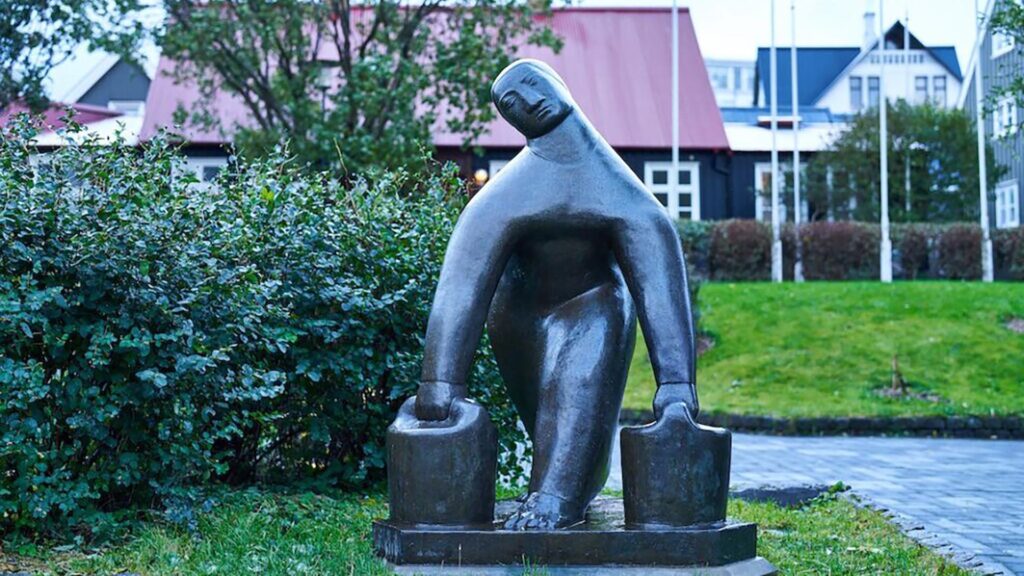

On the corner of the garden by Lækjargata is the sculptor Vatnsberinn or the Water Carrier (1937) by Ásmundur Sveinsson. It is dedicated to the women that carried water from the pump to the houses in town. It was meant to be placed there in 1949 but was considered too unconventional, and people thought it wasn’t prudent to advertise this job for poor women. You can read more about it in the Reykjavik Artwork Walk Around the Pond.

Tobba’s Cottage

Walk up Bankastræti and keep on going until you see Skólavörðustígur or Rainbow Street. Walk up the street until you see the Eymundsson bookstore on your left side. There is a sign about Tobbukot (Tobba’s Cottage), after midwife Þorbjörg “Tobba” Sveinsdóttir, who owned the house that stood there.

The first house on the plot was built in 1858, and Tobba bought it shortly after it was completed. In 1898 she had it torn down and built a two-story wooden house, and she lived there until she died in 1903. The house was demolished in 1968 to make way for the building which is there now.

Tobba studied midwifery in Copenhagen’s maternity hospital and graduated in 1856. This one-year training program was the only one available to Icelandic women. She worked as a midwife until her retirement in 1902, age 66, one year before she died.

One of her last deliveries was that of a baby boy in a little house at Laugavegur 32. The boy, Halldór Guðjónsson, would later take up the pen name Laxness and ultimately win the Nobel prize for literature.

Tobba was one of the founders of the Icelandic Women’s Association in 1894. It was the first women’s association in Iceland to include women’s rights in its manifesto.

Laugavegur – Pool Road

Walk down the small street between the old prison (on your left side) and the bookstore. When you come to Laugavegur shopping street, turn left.

A sign about the Laundry Women of Reykjavik is on the corner of Laugavegur and Rainbow Street.

Laugavegur means Pool Road and is named after the old laundry pools in Laugardalur Valley (Pool Valley). Women carried laundry the 3 kilometers from downtown Reykjavik to Laugardalur to use the geothermal pools until 1930.

Housewives and laundry women began the trek early in the morning. They had to carry the laundry and everything that went with it, washing board, basin, soap, soda, coffee, food, and more. Women usually did this on their own, but their husbands occasionally went with them. Foreign fishermen also used the pools to wash their clothes.

Then they had to carry the wet laundry and baggage back again after many hours of work.

The road to the geothermal pools was not good and could be dangerous as springs and rivers could flood. There are cases of laundry women falling into streams and rivers and drowning due to the heavy baggage they carried on their backs.

Arnarhóll Hill

At the next intersection of Bankastræti and Ingólfsstræti, turn right. One of the cultural signs is at the corner of Arnarhóll hill and Hverfisgata. This one is about Arnarhóll and the farmstead. The farm stood where the statue of Ingólfur Arnarsson is now.

It is believed the farm was founded shortly after the settlement of Iceland (around 870). The oldest relics unearthed during archaeological digs in 1995 dating from the 12th or 13th century. However, the excavation didn’t include the whole hill, so further research is needed to reveal older remains.

When the Government house was built in the 18th century, initially as a prison at the south end of Arnarhóll, the grounds went under the purview of the prison. With that, the farm went into disrepair and was demolished in 1828.

Well into the 19th century, the main route to the east of Iceland from Reykjavik was along the shore (where Hafnarstræti is now), by Arnarhóll, then up to Skólavörðuholt (where Hallgrímskrikja church is now), then towards Öskjuhlíð (where Perlan is), where it forked. One lane went to Hafnarfjörður, the other up to Árbær, through Bústaðavegur and Elliðaárdalur Valley.

To reach Arnarhóll from Hafnarstræti, people had to cross a brook called Arnarhóll Brook. The crossing could be tricky until a bridge was built at the end of the 18th century.

The Stone Bridge

Walk down the street towards H&M, and keep on going until you reach Bæjarins beztu hot dog stand, which you can try on our Reykjavik Food Lovers Tour. Across the street from the hot dog, you will see a portion of the old stone bridge, which was the first stone bridge in Reykjavik.

It was built in 1884 and went under a landfill in 1940. The first harbor in Reykjavik was built in 1917. The Stone Bridge became visible again when the area was redeveloped in 2018, and it was decided to showcase a portion of it.

This marks the end of this short walking tour. As we said at the beginning, there are 62 cultural signs all over Reykjavik, some of which are on Viðey Island. Please check the map below for other cultural signs.

Please signup HERE for our newsletter for more fun facts and information about Iceland!