Tjörnin, or The Pond in English, is a shallow lake in the heart of Reykjavik. Its water comes from Vatnsmýrin to the south, and from the Pond, it flows through Lækurinn (The Stream) beneath Lækjargata, eventually reaching the sea in the nearby bay. The Pond’s picturesque surroundings boast some of Reykjavik‘s most recognizable buildings like Reykjavík City Hall, Iðnaðarmannahúsið, Tjarnarskóli, the Icelandic Museum of Art, the Free Church of Reykjavík, and the scenic Hljómskálagarðurinn Park. The area teems with vibrant birdlife, adding to its natural charm, and families often enjoy the popular pastime of feeding the ducks by the lakeside.

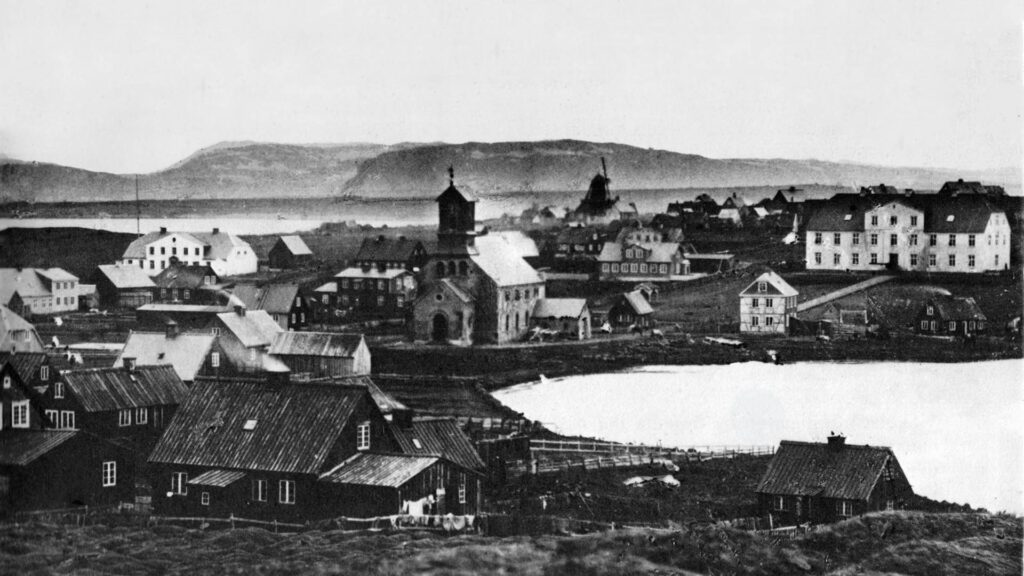

The Pond used to be bigger, but in the last two centuries or so, it has been made smaller to accommodate roads and buildings. One of the reasons why there is no basement in the Parliament building, for example, was its proximity to the Pond and how wet the soil was. Every time they tried to dig for the basement, it flooded.

Vonarstræti: The Street of Hope and Landfills

The origins of Vonarstræti’s name reflect the whimsical humor of the townspeople. Situated on landfills extending into The Pond, Vonarstræti bears witness to the lake’s historical boundaries. In its early days, The Pond stretched nearly to the doors of the Cathedral, emphasizing the significant portion of Vonarstræti that rests on reclaimed land. As the street’s construction progressed, locals playfully dubbed it Vonarstræti, meaning “Hope Street,” acknowledging the perceived long wait for its completion. It’s worth noting that other streets neighboring The Pond, such as Fríkirkjuvegur and Tjarnargata, also sit atop landfills. In fact, Tjarnargata came into existence in 1907 using material sourced from the hill behind the street.

Lækjargata, which translates to Stream Street, was given the sarcastic nickname “The Fragrant Street” during the same period because of the unpleasant odor emanating from the stream, which was contaminated with sewage.

Reykjavik City Hall: A Controversial Addition to The Pond

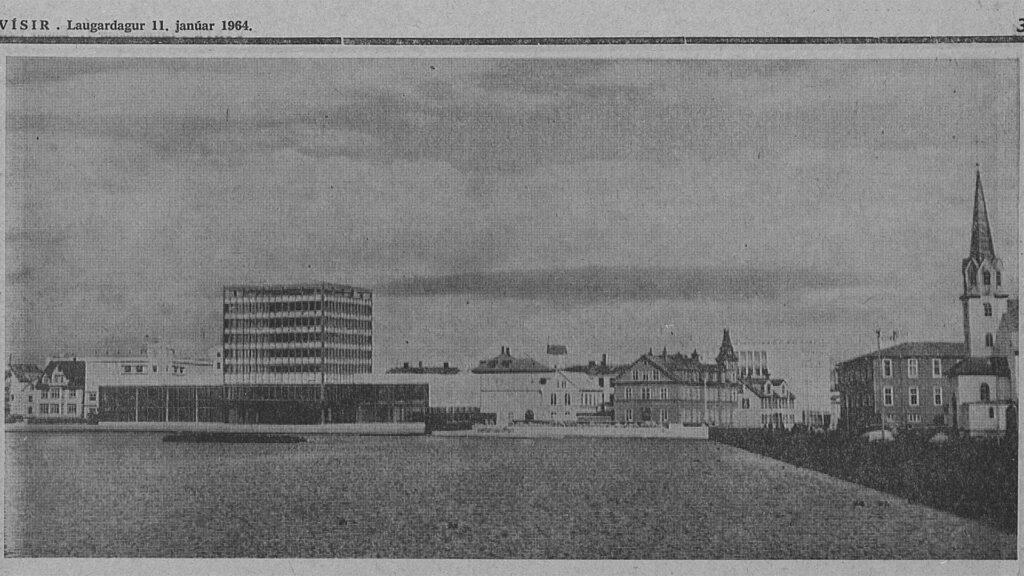

Reykjavik City Hall is one of the most debated structures built on landfills into The Pond. The discussions surrounding its construction spanned several decades before the ground was finally broken in the late 1980s.

For years, plans had been in place to build Reykjavik City Hall at the northern end of The Pond, with various designs gaining approval but never coming to fruition. Architects such as Guðjón Samúelsson and Sigvaldi Thordason had their visions for the town hall, yet it was the design by Studio Granda that ultimately won the selection process, decades later. Initial reactions to the idea of constructing the city hall into The Pond ranged from ridicule to concerns about its size and cost. However, public opinion shifted once the building became a reality.

Back in 1964, a model of Reykjavík’s future town hall was unveiled, showcasing the culmination of years of work by six architects. However, the idea of a town hall in Reykjavík had been in motion even earlier. In 1918, Mayor Knud Zimsen formed a committee to scout a suitable location for the town hall. He even wrote a letter to the Government the following year, requesting a site on Arnarhóll Hill at the corner of Hverfisgata and Kalkofnsvegur. Unfortunately, no response was received, leading to the matter being set aside temporarily. The decision to construct the town hall in The Pond proved controversial, although it should not have come as a surprise, as early zoning plans from 1927 already included provisions for a town hall.

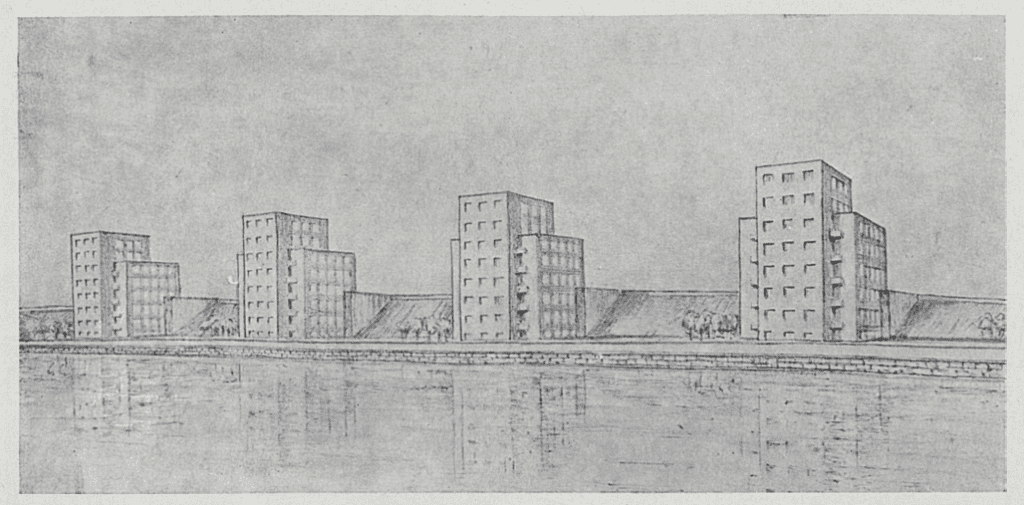

Apartment Blocks Supposed to Replace Old Houses

In the mid-20th century, an architectural competition to enhance The Pond’s aesthetic appeal resulted in six proposals. The winning submission suggested demolishing all buildings surrounding The Pond, including the Free Church and the Midtown School. In their place, apartment blocks were proposed, replacing the envisioned wooden housing complex at Tjarnargata. Today, we can all sigh with relief that these ideas never came to fruition.

Reykjavik City Hall’s establishment within The Pond’s landscape remains a testament to the city’s evolving urban planning and architectural aspirations. While the debates surrounding its construction may have been contentious, the building now stands as a significant symbol of Reykjavik’s civic life and is a prominent hub for municipal affairs.

Ice Harvesting and Economic Growth in Early Reykjavik

In the late 19th century, ice houses were built near the Pond in downtown Reykjavik. These structures served as storage for bait and later became important for preserving food and supplying ice to trawlers for shipping chilled fish to foreign markets.

During the winter of 1919 and 1920, a significant amount of ice, approximately 11,000 cubic meters, was harvested from the Pond. This ice was used for various purposes, such as storage in city ice houses and preserving freshly caught fish destined for British sailings. The revenue generated from these activities provided a welcomed income for the Reykjavík City Treasury.

As demand increased, regulations were put in place, requiring individuals to report the amount of ice they took. An ice inspector was hired to oversee the collection process. In 1915, a record shows the sale of 3,504 cubic meters of ice, amounting to ISK 1,226.40.

This organized approach ensured proper management of ice resources and reflected its importance in Reykjavik’s development during that time. However, it is worth noting that the ice harvested from the Pond was unsuitable for consumption due to the sewage flow into the water.

The Construction of Reykjavík’s Harbour and the Proposal for The Pond

Reykjavík, prior to 1913, lacked a proper harbor until the commencement of its construction, which was later completed in 1917. The need for a harbor in the capital had long been recognized, prompting numerous proposals to address the issue. One intriguing idea, from 1862, involved extending the harbor into The Pond itself. The concept suggested deepening The Pond and creating a dock while simultaneously constructing a navigable canal that would run through the heart of the town, connecting the harbor to the sea.

This proposal garnered attention and was extensively discussed in the newspaper Íslendingur. The author envisioned the cost of this ambitious undertaking to be around 80-90 thousand ríkisdalur, Denmark’s official currency in its colonies. The author expressed confidence that such a structure would not only result in a beautiful and secure harbor but also make better use of the area that was being underutilized.

As the debate unfolded, the realization of a dedicated harbor for Reykjavík finally took shape in 1913. The construction began as the town council realized the new harbor which had been built in Viðey Island would look bad for the capital. At that time, Viðey Island was controlled by the town of Seltjarnarnes. The completed harbor would go on to transform the city’s maritime infrastructure, facilitating trade and transportation while serving as a significant economic hub.

While the idea of expanding the harbor into The Pond did not come to fruition, its proposal stands as a testament to the creative thinking and innovative solutions that were explored during the early development of Reykjavík’s harbor infrastructure.

The Decline of Water Quality in The Pond

The deteriorated state of the water in Tjörnin can largely be attributed to human activities. This issue is not recent, as the lake and its surrounding watershed have faced various disturbances and pressures over the past two centuries, coinciding with population growth and urbanization. The catchment area of Tjörnin has experienced a gradual reduction. Starting with land reclamation efforts during the 18th and 19th centuries, followed by drainage, ditching, and field cultivation in the upper region throughout the first half of the 20th century. Furthermore, the construction of various structures in the 20th century has altered the lake’s banks, often involving landfills and modifications during street and house development projects.

In the past, Reykjavik’s trash dump was literally in The Pond. Although efforts were made to relocate it in 1928, it remained nearby at the southern end of the Pond. Additionally, during the earlier decades of the 20th century, sewage was directly discharged into the Pond, likely continuing until around 1962. Lastly, it is essential to note that feeding bread to birds can induce stress and result in nutrient excretion.

Over time, the ecosystem of The Pond has undergone significant changes. Originally, Tjörnin was a sea lagoon isolated from the ocean by a natural gravel ridge, believed to have occurred around 1200 years ago. The outlet stream once flowed freely into the sea, leading to occasional flooding and tides within the Pond. In 1913, Lækjargata was extended over the Lækur and closed off. Today, a valve system ensures controlled outflow from the Pond, preventing mixing with seawater.

Water Quality in The Pond is Getting Better

In recent years, notable improvements have been observed in the ecosystem of The Pond. Previously, vegetation was scarce in most areas of the Pond for an extended period. However, around 2015, the introduction of small pondweed, an aquatic plant, led to its rapid proliferation, covering a significant portion of the pond’s bottom. Another species, the Alpine pondweed, is also found but is less common, mainly present in Hústjörn.

These developments have positively impacted the lake’s overall life, particularly the notable increase in the population of sticklebacks. Previously, their survival was in jeopardy, but now they thrive. While blue-green bacteria experienced significant multiplication during past summers, in recent years they have been observed mainly in spring without extensive blooms. Though fish, other than sticklebacks, have likely entered Lækurinn (The Stream) and Tjörnin in previous years, their presence and thriving remain uncertain.

The bottom of the Pond harbors diverse groups of organisms. The most dominant being Oligochaeta, followed by microscopic crustaceans known as Cladocera, larvae of non-biting midges, and another group of crustaceans called Copepoda. These groups are commonly found in the sediment of lakes. The diverse and thriving organisms within The Pond contribute to its ecological balance and underscore its significance as a unique natural habitat.

Bird Life and Conservation Efforts at The Pond and Vatnsmýri

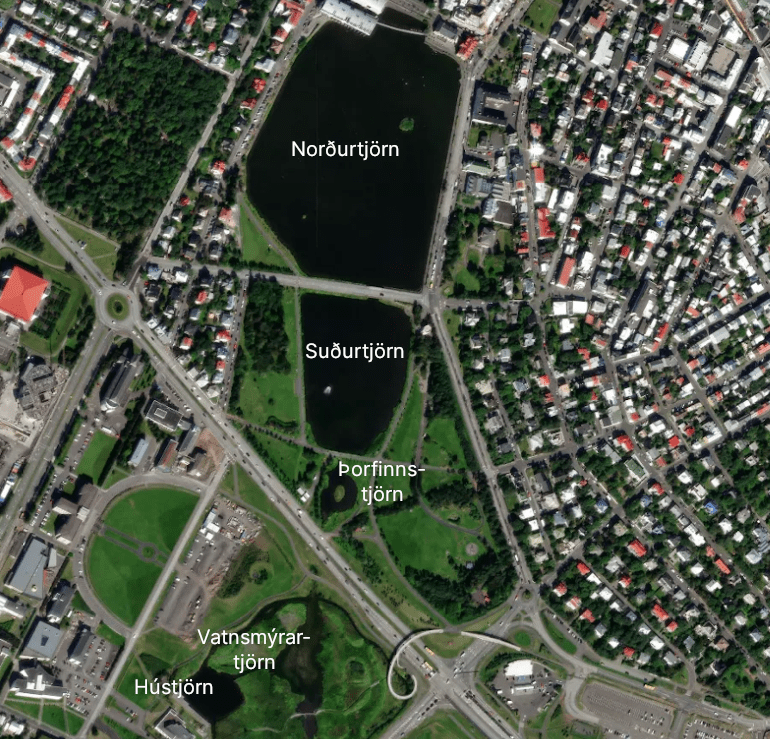

The bird population in the Vatnsmýri area and around The Pond shows variability from year to year. The primary nesting sites include the islets in Norðurtjörn, Þorfinnstjörn, and the nature reserve in Vatnsmýri. To protect the reserve during the breeding season, canals have been constructed to restrict human and cat access.

Certain bird species, such as the Arctic tern, black-headed gulls, mallards, scaup, and tufted ducks, have been consistent breeders since monitoring began in 1973. Other species like teals, wigeons, and red-breasted mergansers, have had irregular breeding patterns in recent years. Although waders are observed less frequently, it is known that European oystercatchers and common snipes breed in Vatnsmýri, albeit with fewer pairs each year. While geese and swans can be found year-round, they do not breed in the area. Occasional sightings of gadwalls, pintails, and rare ducks like shovelers add to the diversity of the bird population.

Birds Didn’t Thrive due to Hunting

In the early 1900s, bird hunting was prevalent, and no bird was safe around The Pond. Duck hunting persisted until the 1910s when a police decree prohibited shooting in the urban area. At the same time, a sailing ban was implemented. These measures contributed to an increase in mallards and Arctic terns as their populations thrived without hunting and disturbance.

In 1984, a nature reserve was established at The Pond and Vatnsmýri to protect and conserve the area’s natural habitat.

Currently, efforts are underway to enhance bird habitation by restoring and adding new islets in The Pond. The City of Reykjavik has announced plans to address the overgrowth of Angelica on the existing islets, which has made them less suitable for nesting and roosting. Erosion has also affected the size of the larger islet. Proposals to repair erosion and create additional islets have been presented to the City’s Environment and Planning Council. The aim is to establish a cluster of islets that will better serve the needs of the bird population.

These ongoing conservation initiatives aim to safeguard the diverse bird species and promote their flourishing presence in The Pond and Vatnsmýri for years to come.

The Pond‘s Catchment Area

While The Pond’s catchment area extends modestly up to Þingholt and Landakotshæð, the precise boundaries around the airport remain somewhat unclear. With an estimated size of approximately 3 km2, a significant portion lies beneath houses, sidewalks, and streets. Rainwater from these urban surfaces is efficiently collected through the city’s sewer system, directly flowing into the sea. Furthermore, rain that falls on gardens and open areas permeates the soil, eventually finding its way to Tjörnin. Additionally, the lake receives a substantial inflow from the overflow of Reykjavik Power Company’s operations in Öskjuhlíð, further contributing to its water volume.

The Pond, encompassing a total area of 8.7 hectares, is divided into distinct sections. To the north of Hringbraut, one can find Norðurtjörn and Suðurtjörn, with Skothúsvegur acting as the separator between them. Þorfinnstjörn graces the vicinity of Hljómskálagarðurinn. Within Vatnsmýrin itself, two artificial parts exist Vatnsmýrartjörn and Hústjörn. The average depth of the different sections varies slightly, with Norðurtjörn averaging around 50 cm and reaching a maximum depth of 90 cm. The southern part of the lake maintains a relatively consistent depth of approximately 50 cm. Hústjörn, on the other hand, boasts the greatest depth at 1.1 meters, while Vatnsmýrartjörn remains the shallowest, with a maximum depth of 35 cm.