One of Iceland’s most famous architects is Guðjón Samúelsson. Just like sculptor Einar Jónsson seems to have created every other statue in downtown Reykjavik, Guðjón Samúelsson designed many of Reykjavik’s most recognizable buildings.

He was State Architect for most of his professional life, just as Iceland gained independence. He was born in 1887 in South Iceland and moved to Copenhagen in 1908 to study architecture. In 1917 he graduated as an architect after a couple of years of sabbatical in Iceland.

Neoclassicism to Modernism

Guðjón was a part of the Garden City movement, which was popular in the early 20th century. The urban planning movement promoted satellite communities surrounding the central city and separated them with green belts. These Garden Cities would contain proportionate residences, industries, and agriculture areas.

He followed the trends of architecture, despite sometimes being criticized for being a bit late to adopt them. Neoclassicism with modern features, often called Nordic Classicism (Austurstræti 16 is a good example), dominated his earlier years. In later years he was heavily influenced by Functionalism and Modernism.

Guðjón was, without a doubt, the most influential architect of Reykjavik’s years.

The Acropolis of Icelandic Culture

When Icelanders got home rule in 1904 and later independence in 1918, we finally dared to start thinking big. There was no Danish monarchy looming over them, holding the purse strings. However, that also meant the government had less money and shallower pockets to dip into.

One of the most ambitious construction plans was for the Acropolis of Culture in the mid-1920s. It was, of course, a time when the world (at least the Western world) was on a constant shopping spree and having the time of their lives… which would eventually come crashing down, as we all know.

Guðjón was tasked with planning this hilltop and, at the time, the highest point of Reykjavik. He lived most of his life in a house his father built on Skólavörðustígur 35 in 1909, and in 1916 he submitted his first ideas for public buildings on the hill. In the following proposal from 1924, he had fully formed the concept. At the top of Skólavörðustígur, people would walk through an archway onto a large square, and in its middle would be a large equilateral cruciform church built in the classical style (like all other buildings on the hill).

On either side of the archway would be residential buildings (Hotel Leifur Eiriksson is now on the left side of the street). Behind the church, he envisaged university student housing. In the top right corner was a “museum house,” which would be home to all the biggest Icelandic Museums, the National Gallery, the National Museum, and the Museum of Natural History. That was never built, but there’s a kindergarten there instead.

Comprehensive building plans were confirmed in 1927 for Reykjavik. The plans for the hill were, in many ways, the same as Guðjón’s ideas. It was also confirmed that Reykjavik City Hall should be built on the northern side of The Pond – something that wouldn’t happen until the early 1990s.

However, as often happens, nothing was to be of this grand idea, maybe for the best. A few buildings point towards the lofty Acropolis of Icelandic Culture. Hallgrímskirkja was built instead of the equilateral cruciform church. The museum of Einar Jónsson was built in 1924. Then there are school buildings for all stages of education apart from university.

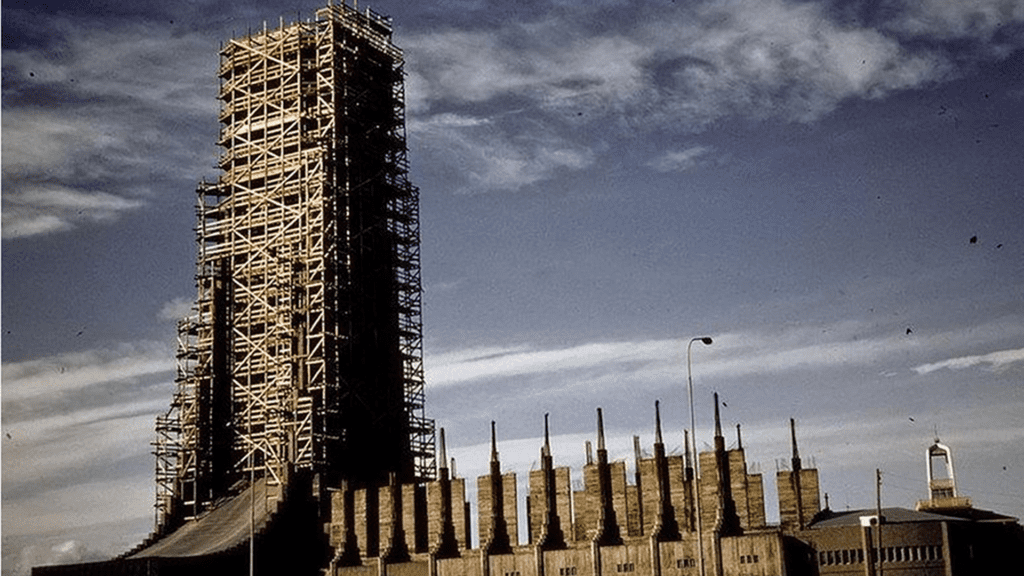

Hallgrímskirkja Church (1945-1986)

Hallgrímskirkja is undoubtedly the best-known Icelandic landmark and definitely one of Reykjavik’s most recognizable buildings. It is 74.5 meters (244 ft) tall and was, for a long time, the tallest structure in Iceland.

The biggest reason the Acropolis of Icelandic Culture was never built was doubts over whether the University of Iceland could grow enough in the area. In 1930, the mayor of Reykjavik offered the state land south of The Pond, which was accepted. It is, to this day, the main area for the University of Iceland.

In 1937 Guðjón was commissioned to design a church for the hilltop, where he had just 12 years earlier envisioned a cruciform church. He had grown with the times and had different ideas on how the church should be this time. The church was supposed to commemorate the devotional poet, Rev. Hallgrímur Pétursson (1614-1674). It was also supposed to be a parish church and a “shrine” for the nation.

In 1942, Guðjón’s designs were approved, construction began in 1945, and a semi-circular chapel was built where the church’s chancels were to be. This would be the only part of the church to be made while Guðjón was still alive.

The church was consecrated in 1948, but it wasn’t until 1986 that construction finally finished.

National Theatre (1930-1950)

The National Theatre was Iceland’s largest building when it was built but also the most sophisticated and well-built. Never had an Icelandic architect undertaken such a specialized and large project before.

As with many of Guðjóns’ buildings, it took many years to finish the construction. It began with his designs in 1925, and construction wasn’t completed until 1950, when he died. During that period, a lot changed in the world and his style.

Despite the looming Great Depression, it was decided to start building in 1930. Builders finished building the exterior structure in 1933 when funding ceased. It stood empty for years; the British and American armies commandeered the theatre during World War II.

After the war, construction began again, and the final interior fittings reflected new trends in style. It is believed the success of the building is because Guðjón had complete artistic control over the process. He had power over every detail of the theatre, apart from the location.

Initially, there was supposed to be a square in front of it, but that never happened, so now people can never fully enjoy the building’s grandeur.

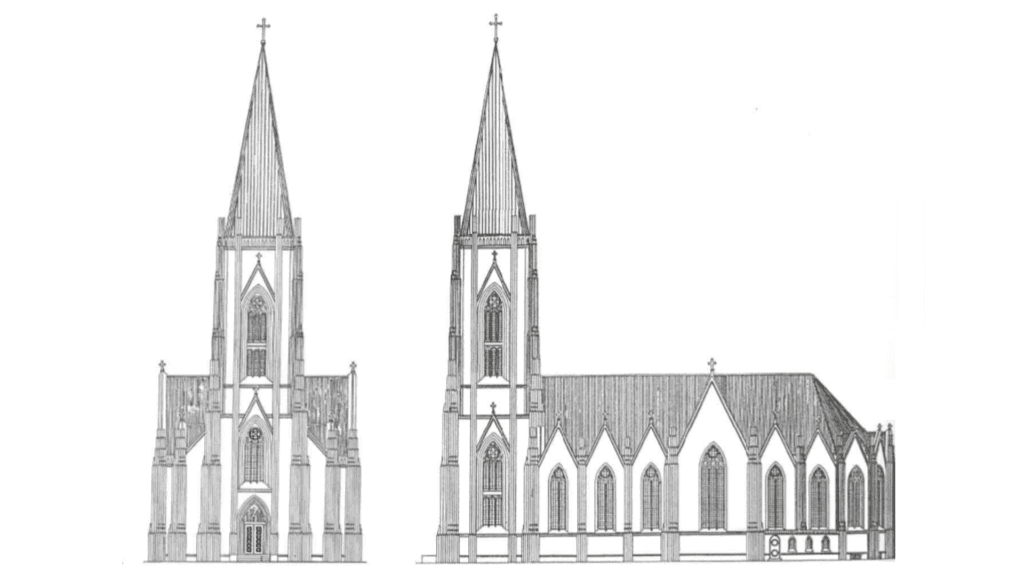

The Basilica of Christ the King (1927-1929)

Another one of Reykjavik’s most recognizable buildings is the Catholic church on top of Landakot hill. The cathedral was sanctified in 1929 and is by many considered one of Guðjón’s most essential works. It is built in a neo-Gothic style. Due to frequent earthquakes in Iceland, building a cathedral with columns and vaults of cut stone was impossible, as is common in other countries. The obvious material for the building was concrete, even if it had hardly been used at the time for neo-Gothic churches.

The concrete presented technical and aesthetic problems, which the architect and builder had to resolve. At the time, the concrete columns were a technological triumph. The cross-vaults between the columns were made using lightweight pumice concrete mounted on wire netting. Guðjón combined Gothic features with Icelandic elements inside the church, which were drawn from nature and vernacular architecture. The gables on either side of the nave remind us of typical Icelandic farm buildings, for example.

Original drawings showed it was supposed to have a higher tower, but for whatever reason, it was never finished.

The National Gallery of Iceland (1916)

This building was not built for the gallery. It was initially built as an icehouse. Ice was collected from The Pond in front of the house. The house (and others like it) were intended for storing bait for fishing. It quickly became important to keep food for the people of Reykjavik. They also provided ice for trawlers, which then sailed to foreign markets with chilled fish.

The Progressive party later used the house for offices and meeting rooms. Then in the early 1960s, a famous nightclub was opened there; however, in 1971, a fire broke out, and everything on the top floor of the house burnt.

Originally, there were ideas about rebuilding the club, but the club’s neighbors protested. A year later, the National Gallery bought and renovated the building; they moved in in 1987.

Reykjavik Swimming Hall (1929-1937)

The Reykjavik Swimming Hall was a collaborative work between the state and Reykjavik. It was the first sports facility of a standard comparable to those in neighboring countries.

Guðjón familiarised himself with the newest swimming pool designs in other countries and made study visits abroad at his own initiative. The swimming pool was unique from other swimming pools in the Nordic countries, as it was heated with surplus hot water from Iceland’s first geothermal district heating system.

The original swimming pool drawings were in the spirit of Romantic Nationalism that appealed to Icelandic youth and sportspeople in the early 20th century. However, the design became totally different after the Scandinavian study trip in the late 1920s. He incorporated ideas from state-of-the-art swimming pools abroad. Among them were the private changing rooms, which are still open.

Despite construction beginning in 1929, it ceased between 1931-1935 due to the Great Depression and disputes over funding. The swimming pool finally opened its doors in 1937. In 2013, the pool was enlarged, and an outdoor pool was added.

Other buildings of interest: Austurstræti 16 (Hotel Apotek), Hotel Borg, The National Telephone Company House by Austurvöllur (now part of Icelandair Hotels), the main building of the University of Iceland, Pósthússtræti 11 (Radisson SAS), Arnarhvoll (Ministry of Finance and Economic Affairs), The main building of the National Hospital, Austustræti 7 (the first concrete building in Iceland)

Main source: Guðjón Samúelsson, húsameistari. Published 2020

Please signup HERE for our newsletter for more fun facts and information about Iceland!