The baðstofa, a central feature of traditional Icelandic turf houses, offers a unique window into Iceland’s past. Amid challenging weather conditions, this communal room became a focal point for shelter and daily life.

Simply constructed with turf, stone, and wood, the baðstofa was a space where families congregated. It was here that many would sleep, work, and share stories. Throughout the long Icelandic winters, it served as a warm hub where the young and old would gather, keeping traditions alive by narrating sagas and engaging in communal activities.

In this blog, we’ll delve into the baðstofa’s history, design, daily role, and importance in Icelandic history and culture.

A Short History of Icelandic Architecture

From the time of their initial settlement, Icelanders predominantly resided in turf houses of various designs. Like their Scandinavian counterparts, they constructed longhouse-style settlement huts with central long fires. These structures boasted curved, lengthy walls crafted from turf, rocks, and timber. A defining feature of these longhouses was the pair of pillar rows that flanked the central fire.

For nearly 900 years, this architectural style remained the primary choice for Icelandic dwellings. As centuries passed and timber became scarce, these houses began to shrink in size. By the 18th century, the dominant design was the “passage farmhouse,” akin to a row of connected houses with a central hallway. The timber used in construction was reserved for the front facade, which also housed the main entrance.

However, the 18th century marked an architectural evolution for the Icelandic elite. Skúli Magnússon, recognized as the first Icelandic treasurer and dubbed the “father of Reykjavík,” commissioned one of Iceland’s pioneering stone residences. Constructed on Viðey Island from 1753 to 1755, this house was conceptualized by a Danish architect. It wasn’t just a residence but also a demonstration of innovative building methods using hewn rocks. Following this, the Danish administration initiated the construction of several stone structures, including the Government building in Lækjargata (originally a prison), Bessastaðastofa (the presidential residence), Reykjavík Cathedral, and Bessastaða Church.

The house on Viðey Island was termed “The Palace” due to its unparalleled grandeur in the Icelandic landscape. Uniquely, each room was equipped with a furnace, a feature previously unfamiliar in Icelandic architecture.

Why “Baðstofa”? A Name’s Evolution

Interestingly, the term “baðstofa”, translating to “bathing room”, is somewhat of a misnomer since, for centuries, it wasn’t a place for bathing. Historians believe that the earliest baðstofas were akin to saunas, where water was sprinkled on heated stones to produce steam. The oldest mention of a baðstofa dates back to the late 12th century, and by the 13th century, these steam rooms were prevalent throughout Iceland. However, by the 15th century, their purpose shifted, and they evolved into common rooms, with their primary heating apparatuses rendered redundant by the 16th century.

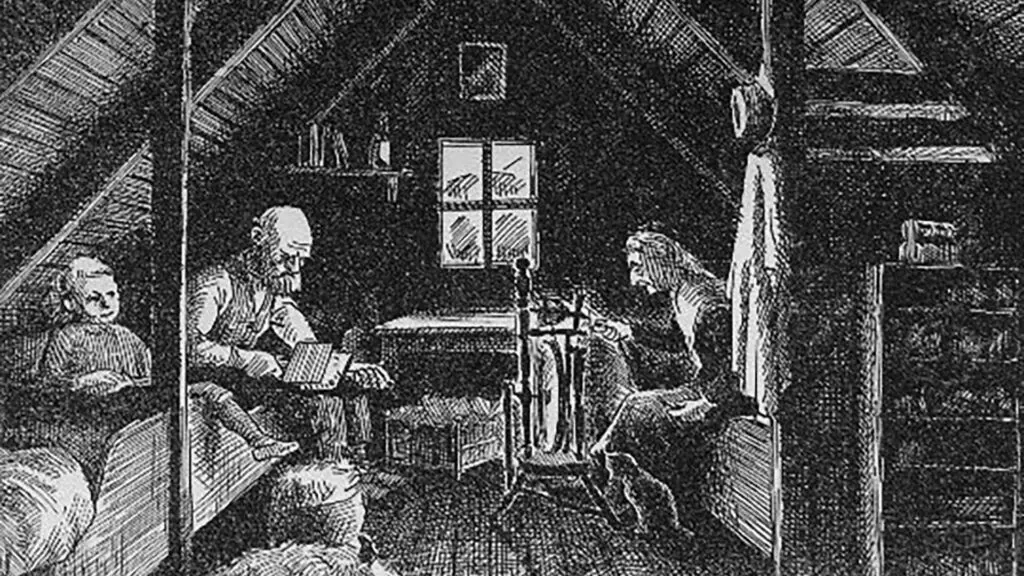

The transition in the name might be attributed to the baðstofa being the sole heated room in turf houses. As wood became rarer, central fireplaces, typical of Viking-era longhouses, vanished, leading inhabitants to the only room with a furnace. Yet even the furnace eventually became obsolete, as Icelandic houses rarely had chimneys. By the 16th century, the baðstofa mainly served as a daytime communal area, a space for relaxation after a day’s work. Only in the 17th and 18th centuries did it assume the role of the house’s main room, where people ate, kept each other company and slept. The rooms were generally rather small, and often, more than one person was in a bed.

The Baðstofa’s Design

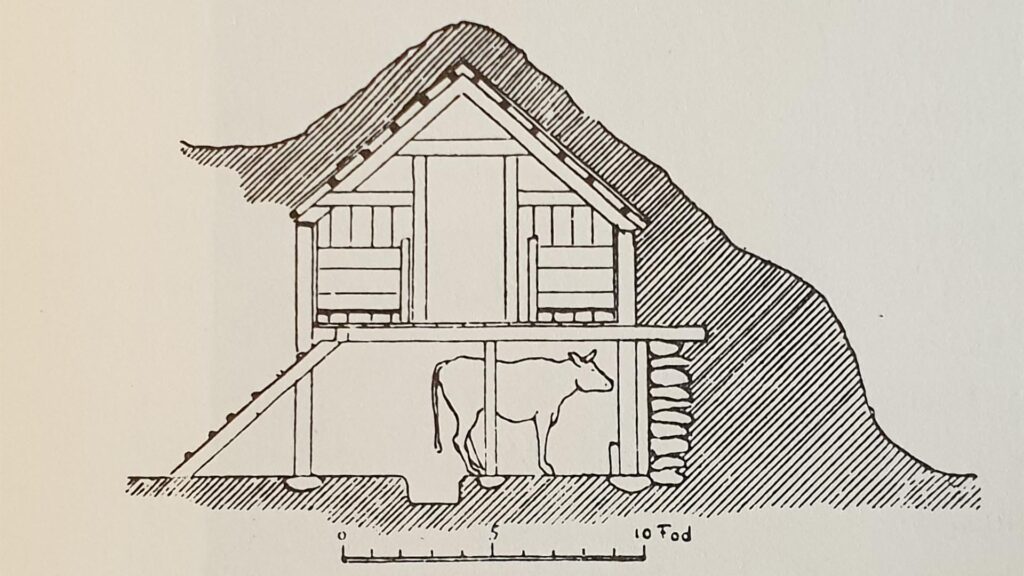

Baðstofas varied in design, particularly during the 18th and early 19th centuries. Large farms often housed these on the upper floor or utilized a platform design. These structures typically featured tall rafters, approximately 6-8 feet, with beams about 4.5 feet from the ground. Beds were aligned alongside the walls. Larger baðstofas even featured a central beam, sometimes lowering the ceiling height significantly.

Keeping the baðstofa above the cow shed was also common. People would inhabit barn lofts during winter, with beds on the sides. Cows below were afforded limited space, often bumping their heads on the floorboards above. Some designs featured wooden floors centrally, allowing for better air circulation and cow movement. These barns lacked windows, but the baðstofas usually had either a single glass window or side screens. The structure was topped with turf laid over rafters, keeping it warm in winter thanks to the cows below and cool in the summers.

The Baðstofa and Its Traditions

The baðstofa was the primary living space in Icelandic homes for centuries, serving multiple purposes. Beyond being a communal area for spinning, weaving, knitting, eating, and sleeping, it was the venue for the significant tradition of “house reading.”

House Reading: An Old Icelandic Custom

House reading was an Icelandic tradition predominantly observed during the 19th century and the early half of the 20th century. At that time, Iceland’s population was sparser than it is today, with most inhabitants living on farms. Due to the scarcity of books and many being illiterate, a designated person in the household would read aloud to the others during the evening. This practice held a solemn significance, as described in a reminiscence: “There were few books in the home. During house reading, everyone remained silent, fully engrossed. Hymns were sung before and after the reading. My mother, a clear and articulate reader, often led the session. I recall an instance when someone misspoke, causing my brother Halldór to smile – a reaction frowned upon.”

This tradition especially thrived in homes located far from churches, making regular attendance challenging. Immediately following the Reformation, house reading was rare due to the limited availability of books and widespread illiteracy. However, the landscape of literacy transformed after Bishop Guðbrandur, depicted on the 1000 ISK bill, initiated his printing workshop in the 16th century.

House reading rituals were intricate. Typically, sessions began and ended with singing psalms, encompassed a prayer, and culminated in attendees thanking the reader, often with a handshake. Notably, the tradition dictated that readings should commence after completing barn work and dinner, followed by bedtime with minimal conversation. The procedure was infused with deep reverence, showcasing Icelanders’ profound respect for the scriptures.

Yet, as the 19th century waned, societal attitudes evolved. Devotion to the church lessened, house readings became less frequent, and the once-hallowed scriptures were sometimes treated with frivolity.

The Sacredness of Sundays

Above all traditions, Sunday was venerated. Any form of work was strictly forbidden on this day. Enjoying a drink post-mass was permissible, but work-related activity was taboo. Popular beliefs held that airing bed sheets on a Sunday foretold an impending divorce. Shoeing a horse on this day meant it would soon become lame, and mending sea clothes would doom the wearer to drown in them.