On May 10, 1940, the quiet island of Iceland was abruptly thrust into the global conflict of World War II. Operation Fork, a code name for the British military occupation of Iceland, was launched to prevent Nazi Germany from using the island as a base for air and naval operations against the British Isles.

The operation was carried out without resistance from the Icelandic population and lasted for the duration of the war. While the occupation of Iceland may not be as well-known as other events of World War II, it played a crucial role in the defense of the British Isles. It had a significant impact on the country’s history and development. In this blog post, which is the first of a series, we will delve into the events leading up to the occupation, the impact of the operation on Iceland and its people, and its lasting legacy.

Reykjavik in May 1940

On the morning of May 10, 1940, the people of Reykjavik were woken by the sound of an airplane flying over the town. Just a month earlier, the Nazis had invaded Denmark, and Icelanders waited with bated breath about what would happen next. Even if Icelanders had gotten their independence in 1918, they were still in a political alliance with Denmark, and the Danish king was also the king of Iceland.

Reykjavik was relatively small in 1940, with a population of about 30,000. Icelanders were still primarily farmers and fishermen. Despite slowly becoming more modern, the country was not nearly as modern as other European cities.

The city had limited infrastructure and amenities, with some paved roads and only a few buildings with more than two stories. It had a small port and an airport, but it was not a major center of transportation or commerce.

Iceland was neutral in the war, and its economy was primarily based on fishing, agriculture, and small industries. They had limited connection with the rest of the world, and the occupation by Britain was a significant event in the country’s history. Icelanders were unprepared for the sudden influx of military personnel and equipment.

Overall, Reykjavik in 1940 was a small, quiet, and relatively isolated community that was not accustomed to the kind of military occupation and foreign presence that it experienced during World War II.

Icelanders soon learned the British were coming, not the Germans.

Operation Fork

When Nazis invaded Denmark and, subsequently, Norway, Winston Churchill, and the British Government had real worries that Nazis would go to the Faroe Islands and Iceland next and block Britain from the North Atlantic Ocean.

The British Government sent the Icelandic Government a telegram when it heard of the German invasion of Denmark. There they offered to help Iceland maintain its independence but would need facilities in Iceland to do so. The Icelandic Government promptly answered no, thank you, Iceland was a neutral nation.

Two days later, the British occupied the Faroe Islands.

At the beginning of May, the Admiralty concluded that Britain could not do without bases in Iceland. Churchill tried to negotiate with Iceland, but the Icelandic Government was firm: Iceland was not going to take part in the war.

So, it was decided that Britain would invade Iceland and present the Icelandic Government with a “fait accompli”; that is, the British were already there, and the Icelandic Government couldn’t do anything about it.

The operation was hastily organized. The decision was made on May 6, and they arrived in Iceland on the morning of the 10th. Much of the operational planning was organized en route to Iceland. The force was supplied with a few maps of the country. Most of them were of very poor quality, and one was even drawn by memory. No one on board spoke good Icelandic.

Badly Equipped Military

Three days before the British Government decided to occupy Iceland, the 2nd Royal Marine Battalion in Bisley, Surrey, was given orders to be ready to depart in two hours for an unknown destination. The battalion had only been activated a month before. Despite the presence of a core of active service officers, the troops were new recruits with little training.

There was also a scarcity of weapons, which were limited to rifles, pistols, and bayonets. 50 marines had only recently received their rifles and had yet to fire them. The battalion received some minor reinforcements on May 4 in the form of Bren light machine guns, anti-tank guns, and 2-inch mortars. With no time to spare, the weapons’ zeroing and initial familiarization shooting would have to be done at sea.

Even though it had been over twenty years since the First World War, the British were not ready to go to war again. This was evident in the men who were sent to Iceland.

Arriving in Reykjavik

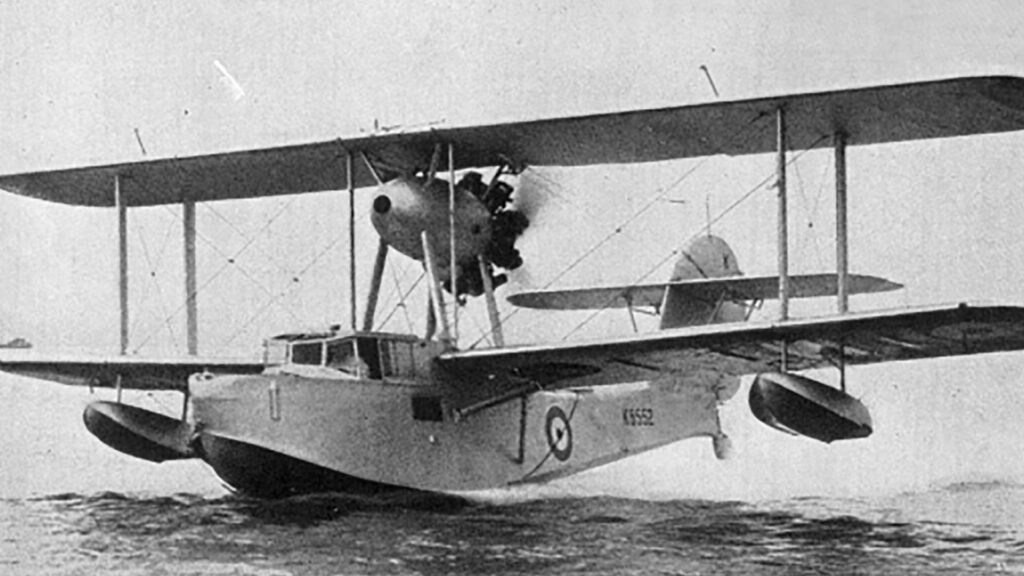

The plan was, of course, to arrive unannounced in the dead of night. However, as already stated, they lost the element of surprise by flying over Reykjavik. That meant when they came to Reykjavik, quite a few people were waiting for them. The plan was to scout the vicinity of Reykjavik for enemy submarines. Due to miscommunication or an accident, the pilot of the Supermarine Walrus aircraft flew several circles over the town.

They were worried about the reaction of the Icelandic people and especially the Icelandic police. However, everything went as planned. The Icelandic Government had decided to let it happen, but they protested.

“Mr. Ambassador.

From the events that took place early this morning, the occupation of Reykjavík, when Iceland’s neutrality was blatantly violated and its independence was impaired, the Icelandic Government must refer to the fact that on April 11, it officially informed the British Government, through its representatives here on land, the attitude of the Icelandic Government to its proposal to provide military protection to Iceland, and according to that, the Icelandic Government violently objects to what the British armed forces have committed.

It is, of course, expected that total compensation will be made for the loss and damage that results from this violation of Iceland’s legal rights as a free and sovereign neutral state.”

British Military Announces Itself

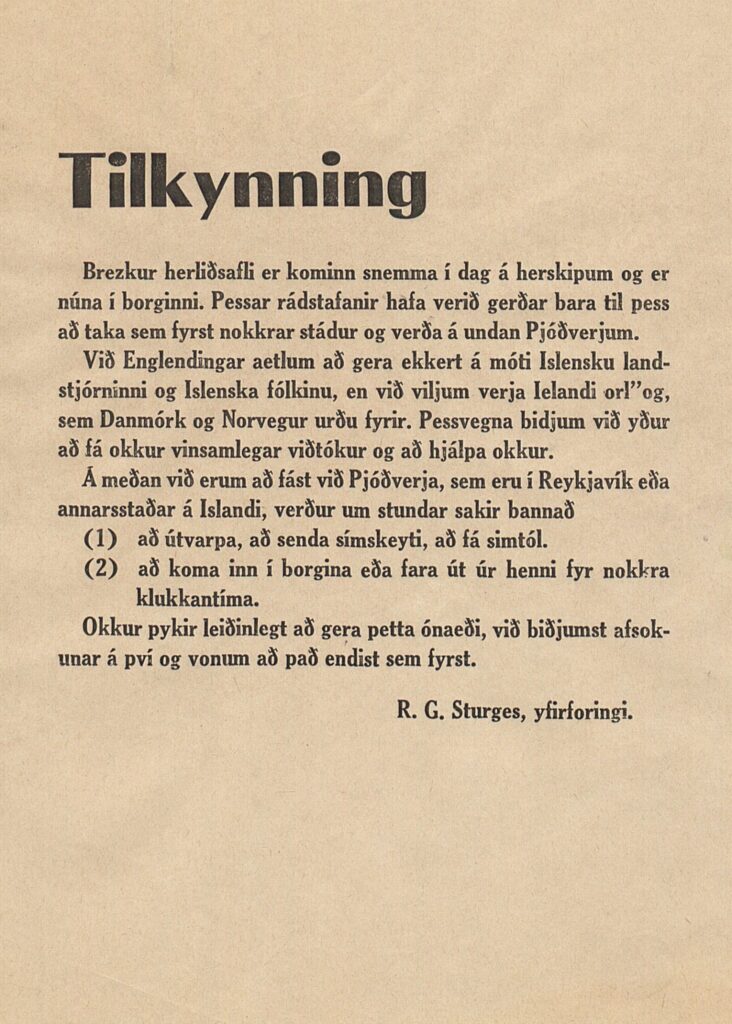

When they stepped on land, they handed out leaflets to Icelanders in broken Icelandic. It said:

“Announcement

British armed forces arrived early this morning on warships and is now in the city. These arrangements have been made to be the first to secure several locations and to be here before the Germans.

We, the English, will not do anything against the Icelandic government or the Icelandic people but wish to defend Iceland from the fate which has fallen to Denmark and Norway. Therefore we as you to give us a friendly welcome and give us assistance.

While we are dealing with Germans, who are in Reykjavík or elsewhere in Iceland, it will temporarily be prohibited to

(1) broadcast on the radio, send telegrams and receive telephone calls.

(2) leave or enter the city for several hours.

We are sorry for the inconvenience; we apologize and hope it ends as soon as possible.

R.G. Sturges, commander.”

The worries of the British Military were unfounded. The only incident was when an Icelander grabbed a rifle of one of the soldiers, stuffed his cigarette in the barrel, and told him to be careful with that.

The German Consul First to be Arrested

Werner Gerlach, the German consul, was awoken shortly after the airplane was first heard by his friends and staff. Who it was that woke him up has never been fully revealed, but it is like that one son of the fire brigade chief had been the one to do it, but he and his brother were known German allies.

They go together to wake up various Germans who live in Reykjavik and are working with them. They return to the Embassy in Túngata and begin burning various sensitive documents in the bathtub.

The plan to burn sensitive documents began quickly after that.

One of the first members of the British Military to step foot on Icelandic ground was Major Humphrey Quill, head of the small intelligence detachment. His job was to arrest Germans, the consul, and his staff, known Nazis and castaways.

Major Quill met with the British consuls (the current and former) and asked them to show him the way to the home of the German consul. About a 30 people entourage walked from the harbor to Túngata.

Inside the consul, people were panicking. The consul and his wife carried documents to the bathtub, doused it with kerosene, and lit it.

A Spy Among the British

Consul Gerlach forbade his people to open the door for Major Quill and his people. However, he heard shouted in clear German that they should open right now. The man who called was the British vice-consul George Edward Hoblyn. He had leaked the information about the British occupation to the German consul just a day before.

After a thorough search through the house and breakfast served by the consul’s wife and daughter, they were arrested and escorted from the house. They were held in HSM Berwick.

Other German citizens living in Reykjavik were on the arrest list of the British army. They were all rounded up and put on HMS Fearless.

George Edward Hoblyn and his German wife were later arrested, and their 8-month-old son was put in foster care in Iceland.

What Happened Next?

In the coming days, the British Military took over quite a few buildings in Reykjavik. Among them was the not-complete National Theatre, Hotel Ísland (which burned down in 1944), storage rooms in Hafnarhúsið where Reykjavik Art Museum is, the sports house by the Catholic Church (which is now in Árbær Open Air Museum), Austurbæjarskóli grammar school (next to Hallgrímskirkja Church), Miðbæjarskóli School by the Pond, Iðnskólinn School by the Pond, the Old French Hospital which then housed a high school but is now Reykjavik Music School, and other buildings. None of these buildings or lands was commandeered. They were all rented and paid for.

In the coming months, about 25,000 British soldiers were sent to Iceland. There was a severe housing shortage in Reykjavik, and they decided they would build Nissen huts. They changed the look of Reykjavik for decades to come.

This is the first part of a few-part series about Iceland in World War II.

My father was a Baker in the RASC in Iceland and I have a photograph of the unit looking at a whale in the harbour in Reykjavik. He was then transported to Italy when the troops landed there.