Everyone knows Halloween. Some believe it is an invention of the candy companies to sell more candy. However, celebrations at the end of October can be seen in many European cultures and over many centuries. But do people celebrate Halloween in Iceland?

The Catholic All Hallow’s Eve, from which the name Halloween is derived from, can be dated back to the 8th century. However, the celebrations we associate with it today most likely come from Ireland and Scotland. Norse people also celebrated during this time and could have influenced the Celtic and Gaelic nations while they ruled them. It is, of course, impossible to say that Halloween in Iceland was celebrated in the days of yore, as it didn’t exist back then. But we did have Winter Nights.

Veturnætur – Winter Nights

This Nordic celebration of Veturnætur, or Winter Nights, dates back to before the nations became Christian. Veturnætur was held in October at the beginning of winter. According to the Old Norse calendar, the first winter day was on a Saturday between 21 and 28 October. It coincided with the beginning of the first winter month of Gormánuður.

The First day of Winter was possibly considered a type of new year as there were only two seasons, summer and winter.

The three-day Winter Nights festival occurred between the end of the summer and before the beginning of winter. All summer months begin on a Thursday, while the winter months begin on a Saturday. So, there is a day between the seasons, and the festival was held from Thursday to Saturday.

It is not known how old the festival is. It is mentioned in Icelandic manuscripts, but there are no descriptions of how it took place. The customs must have been considered such an integral part of society that there was no need to write them down.

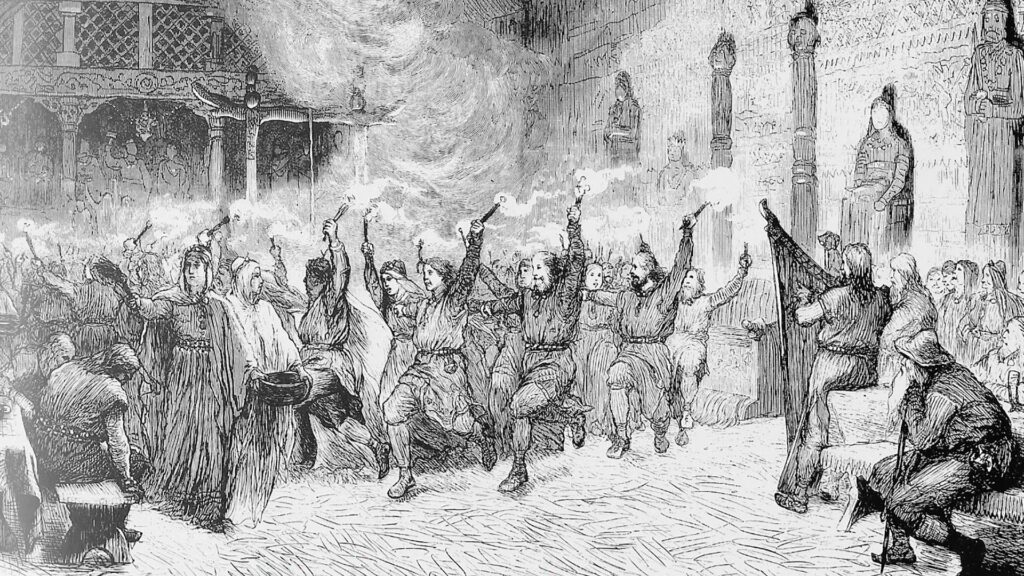

There is a mention of another festival, called Dísablót, in a few Icelandic sagas. Hervarar saga ok Heiðreks konungs and in Víga-Glúms saga, Egils saga, and the Heimskringla. There are no sources of it being held in Iceland, but rather in Scandinavia. Blót is the worship of pagan gods, while dís is a goddess and could have both referred to Freyja and the like as well as valkyries. Blót often involved sacrifices, both blood (from animals) as well as food offerings. It is possible that female supernatural beings, such as witches in European folklore and the Yule Lads’ mother Grýla, are remnants of this old dísa-belief.

Dísablót and Winter Nights were held may be the same festival, or at least possibly held at the same time. According to the Víga-Glúms saga, Dísablót and Winter Nights were held at the same time.

You can read more about dísa-beliefs in our Ghosts, Specters, and Zombies blog.

Slaughtering Season

The Winter Nights festivities likely included slaughtering animals. It was the season for it, after all. And as it was a time of food abundance, there was a cause for celebration. It is also the beginning of winter, darker nights, and new beginnings.

As stated before, winter begins at the end of modern-day October, and the first month is Gormánuður. Gor means half-digested food in animals’ innards, especially herbivores. This was also a popular time for weddings. There was enough food to go around, and thus another way of marking a new beginning. It might even be possible that this time was considered their new year. However, it is not certain when Norse people celebrated their new year. Some believe it is the First Day of Summer, as that’s when the grass starts to grow and a new life begins, so to speak.

There is no mention of Winter Nights in sources from the 12th, 13th, and 14th centuries. But the end of October continued to be popular for weddings.

After the Nordic nations became Christian in the 9th to 11th centuries, All Saint’s Day, which dates back to the 8th century, slowly took over as the main autumn festival. Various Halloween customs can possibly be related to Winter Nights, just like other pagan autumn festivals like the Celtic Samhain. However, it is possible that their timing affected the Celtic and Gaelic festivals because the Norsemen ruled over the British Isles for a long time.

Icelanders seem to have stopped holding the Winter Nights festival shortly after they became Christian in the year 1000. However, the Icelandic pagan association Ástatrúarfélagið began celebrating Winter Nights in the late 20th century and holds a Winter Night Feast on the First Day of Winter.

Supernatural Beings on the Prowl

The beginning of winter and a new year is considered a liminal period. A sort of in-between condition that exists in times of great transitions. People can perceive other worlds, see otherworldly beings, and predict the future.

There are quite a few stories of those in-between conditions in Icelandic folktales. They are mostly related to Christmas day, modern New Year’s Eve, or the Thirteenth Day of Christmas (the last day of Christmas in Iceland).

Spirits are on the prowl during Samhain, and the boundaries between the worlds of the living and the dead were considered blurred on this night. Ghosts, witches, and other undead were believed to be hovering aground, so bonfires were lit to protect the living. People disguised themselves and offered food and drink to the creatures to appease them. This isn’t unlike the liminal period during Christmas, New Year, and the last day of Christmas in Iceland. Midsummer is also a period where this in-between condition exists.

Modern-day Halloween

As Icelanders became Lutheran in the late 16th century and Catholicism was banned, there are no All Hallow’s Eve and All Saint’s Day customs in Iceland.

The custom of marrying on the First Day of Winter died out. And there are no celebrations connected to the day in modern-day Iceland (apart from the aforementioned custom of the Ásatrúarfélag). Unlike the First Day of Summer, the First Day of Winter is not a national holiday – but as it is always on a Saturday, many people have the day off.

However, unlike the First Day of Summer, which people think more of today as the first day of spring, the First day of winter is believed to be the beginning of winter.

In the last 20 years, Halloween has become increasingly popular in Iceland but strictly in the commercial sense. Colleges hold Halloween balls (as well as many bars and clubs), and children have begun walking from door to door asking for treats. But since Halloween in Iceland isn’t a native celebration, how do children know where to go to ask for candy? Well, if you see a pumpkin outside or in the window, you can come and ask for candy.

Other Halloween traditions have started to seep into Icelandic society. Many people wait in excitement for the pumpkins to arrive in stores (they aren’t grown in Iceland). Coffee houses have begun offering pumpkin spice lattes, and clothing stores offer all kinds of Halloween goodies.

Of course, not everyone is keen on this celebration coming to Iceland. Many view it as a commercial holiday created in the US. But maybe it is possible to combine the old Icelandic tradition of Winter Nights with Samhain and Halloween customs and create a unique Halloween in Iceland celebration.

The Icelandic Costume Day Öskudagur

Icelanders have their own costume day, Ash Wednesday (held the day after Mardi Gras). As it is always on a Wednesday, children get the day off school and go between stores and companies singing for candy.

Read more about the day here.

What is your favorite Halloween tradition?

Please signup HERE for our newsletter for more fun facts and information about Iceland!