While Iceland has consistently been ranked as the most peaceful country in the world since the Global Peace Index was launched in 2009, and it’s known for not having an army, its history is scattered with a few conflicts. From its early days in the 9th century, Iceland has seen everything from chieftainship feuds and a 13th-century civil war to a government coup led by Jørgen Jørgensen in the 19th century, where he briefly claimed Iceland’s independence from Denmark.

One of the more harrowing episodes in Icelandic history occurred in the 17th century with the “Turkish Abductions,” where pirates from Algeria raided the coast and abducted Icelanders. The country also faced the challenges of occupation by British and American forces during WWII and, later, the Cod Wars, a series of confrontations with British naval forces over fishing rights.

This blog post will walk you through the Icelandic forts and strongholds that witnessed some of these turbulent times, illuminating the contrast between Iceland’s peaceful present and its tumultuous past.

Borgarvirki in West Iceland

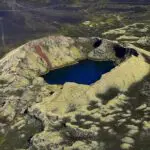

Perching on a ridge between Vesturhóp and Víðidalur, Borgarvirki is the oldest Icelandic fort on this list and rises about 177 meters above sea level as a formidable rock fortress. Its origin as a volcanic plug dates back to an eruption during a warm period of the Ice Age. The summit, marked by a 5-6 meter deep horseshoe-shaped crater with an eastward opening, underwent restoration in the 1940s and 1950s, where workers rebuilt an ancient stone wall and added several structures. Today, it stands protected as a historic site, home to the remnants of two huts and a collapsed well.

Legend tells us that Borgarvirki was a strategic stronghold during the Icelandic Commonwealth Era. According to the sagas, Víga-Barði Guðmundsson from Ásbjarnarnes took shelter in Borgarvirki to fend off conflicts with the people of Borgarfjörður, as the Heiðarvíga saga recounts. When his enemies from the south advanced with an ill-prepared army, Barði, forewarned, secured himself and his men within the fortress, making it an impenetrable refuge. The besiegers from Borgarfjörður attempted to starve out Barði and his forces. As their food supply dwindled, the defenders cleverly threw their last bit of suet over the fortress walls, tricking their adversaries into believing they were well-supplied, forcing them to abandon their siege.

The Fort of Bessastaðir

The Turkish Abductions had quite an effect on the small population of Iceland. During the raids, about 50 people were killed and 400 were abducted. The first iteration of the Fort of Bessastaðir was built in haste to defend the royal Bessastaðir estate against potential pirate attacks. In 1627, pirates who had previously looted Grindavík and aimed to attack Bessastaðir navigated into Seylan, only to run their ship aground on a shoal, prompting them to abandon their plans. By 1688, The Fort had been equipped with numerous cannons designed to protect against pirate threats and other dangers, although these cannons ultimately went unused.

Bessastaðir is now the residence of the President of Iceland.

Lackluster Defenders

Historically, Bessastaðir has been a strategic military site and scene of conflict, notably during the 1627 Turkish Abductions. Even with cannons ready and commanders “heroically” armed and mounted on gilded saddles, the actual fighting fell short of glory. Notably, the command had preventive measures, including a horse ready for a quick escape.

When pirates landed at Reykjanes in June 1627, taking captives from Grindavík and planning to circle westward back to the country, the news quickly alarmed Bessastaðir, then under the leadership of Holger Rosenkranz. With Seylan hosting a poorly defended merchant vessel and additional ships in Hafnarfjörður, Keflavík, and Hólmshöfn, all were summoned to Bessastaðir, resulting in three ships being stationed at Seylan. Onshore, defensive measures were enhanced by Seylan constructing a fort from turf and stone. Bessastaðir’s cannons were relocated for this purpose. To bolster the fort’s defence, the steward conscribed various officials.

On the night before St. John’s Eve, pirate vessels were seen sailing past Álftanes toward Seylan, unleashing volleys of cannon fire. The defenders at The Fort fired back. Despite the exchange, the pirates hoped to plunder the ships anchored in Seylan. The attack sent shockwaves of fear through the local community, driving residents to flee. In a desperate bid for safety, families and their livestock retreated to shelters in the mountains or deeper into the volcanic fields.

Stranded Pirates

When the pirate ships arrived, one of them became stranded in Seylan. Nevertheless, its crew skillfully relocated captives and loot to the accompanying vessel, thus setting it free. Jón Ólafsson, known for his voyages to India, said in his book, published in 1661, that: “Cannons roared from both shore and ships, signalling the start of the conflict. “But by what seemed like a stroke of divine luck, a pirate ship was stranded by the rising tide, laden with captives and most of their spoils.” To salvage the situation, the pirates began moving people and goods onto the other ship, discarding a significant amount of flour, beer, and other hefty cargo into the sea. Amid this frantic activity and the chaos at sea, the Danish counterattack unexpectedly halted, much to the chagrin of the Icelanders, who advocated for continuous engagement amidst the disorder. Their pleas went unheard…” Following this, both pirate ships departed Skerjafjörð without encountering further opposition.

Subsequently, Bessastaðir saw sporadic instances of military activity or service. After the raid, Holger Rosenkranz came with four warships for defence and surveillance the following year. Over time, a consensus emerged on needing a permanent fortification at Bessastaðir, above Seylan. By royal decree on July 3, 1667, a levy was imposed on the populace to fund the erection of Bessastaðir Fort the following year. This tax, colloquially dubbed “Ottagjaldið,” was met with public disfavour.

Initial resistance to this levy was sometimes met with punitive actions in certain locales. However, Bishop Brynjólfur (the man on the 1000 ISK bill) intervened, coaxing the populace into acceptance to avoid imposing a sterner charge.

Bessastaðir Cannons

The cannons found at Bessastaðir might have originated from the royal armoury, intended for defensive measures or to assert the authority of the local leader over his people. There’s also a chance they were acquired from trading vessels along the coastline. Given the international maritime traffic of the era, the Bessastaðir cannons could have been manufactured in different countries and obtained through the global interactions of ships visiting or fishing near Iceland.

Considering Bessastaðir’s distant position in the Danish empire, it probably didn’t receive the newest and most advanced armaments, implying that the site might have retained older cannons for a longer period compared to fortifications nearer to the monarch’s reach. Having outlived their military usefulness, the cannons were likely repurposed for firing salutes at official events and some of which were moved to Reykjavík when Jørgen Jørgensen built the Battery in Reykjavik in the early 19th century.

Dating back to the 15th and 16th centuries, these cannons were possibly used at Bessastaðir for defensive purposes well into the 17th century, if not beyond.

Fort Phelps in Reykjavík

Batteríið, or Fort Phelps as it was initially called, was a fort Jørgen Jørgensen had built in 1809, standing where The Central Bank stands today. Following Jørgensen’s takeover of all governing powers in Iceland during the summer of 1809, whom locals dubbed Jörundur The Dog Days-King, the need arose to fortify Reykjavík for protection.

A decision was made to erect a bastion on the cliff of Arnarhóll at the former intersection of Skúlagata and Kalkofnsvegur.

The fort’s construction was primarily managed by a merchant and Jørgensen’s partner, Phelps, leading to the decision to name the stronghold Fort Phelps. Historically, Iceland’s arsenal was notably sparse. Yet, it was recalled that cannons had been positioned at the Bessastaðir fort shortly before 1670. Despite being partially buried and corroded, these cannons were transferred to Reykjavík and installed in the fort. Consisting of six cannons suited for six-pound shots, they were refurbished and made operational. Malmquist, an employee of Phelps working in Brúnsbær, was named the fort’s commander.

Central Bank Built on The Fort

Following the end of Jørgensen’s brief reign, the fort received little attention. Espólín’s* annals recorded that most cannons were believed to have been transported to the sea and submerged. The demolition of the Battery was inevitable with the commencement of harbour construction in 1913.

The Central Bank now occupies the site where the Battery was located at the start of the 20th century, and its layout partially mirrors the former fortification.

*Jón Espólín (1769–1836) was an Icelandic writer and official best known for his contributions to documenting Icelandic history. His most notable work is “Árbækur Íslands” (Annals of Iceland), a comprehensive historical account spanning from the settlement of Iceland to his contemporary 19th century. This work, divided into several volumes, remains a valuable resource for understanding Iceland’s history, culture, and society during this period.

Skansinn or The Fort in Vestmannaeyjar

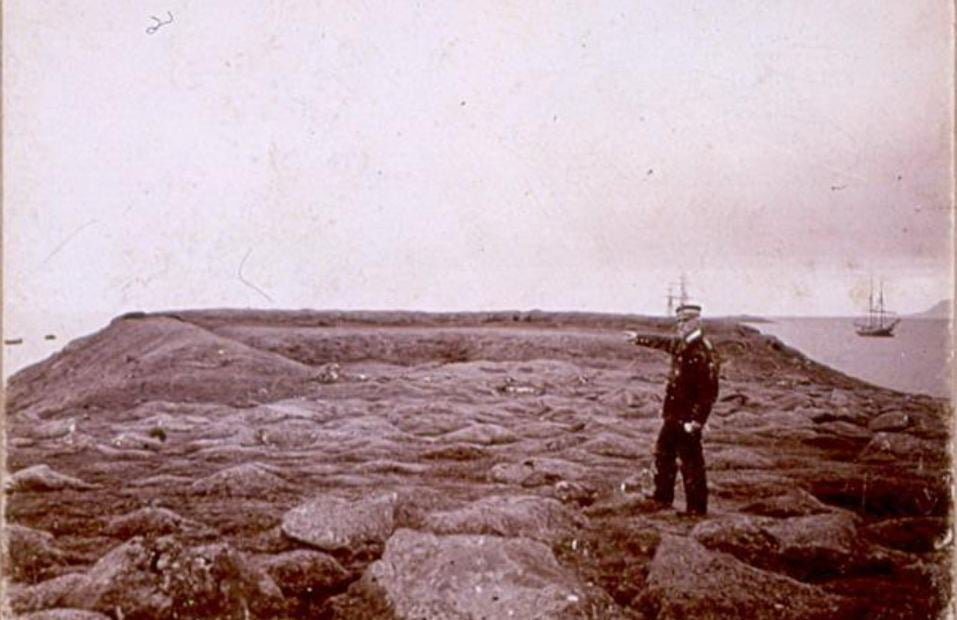

In the late 16th century, the king ordered the construction of Skansinn (The Fort), a strategic fortress in the Westman Islands, to shield the islands — especially the royal assets — from English traders and raiders. Lava from the volcanic eruption of 1973 partially buried Skansinn.

On April 18, 1586, Frederick II, the King of Denmark, tasked Captain Hans Holst with building a fortress at an optimal location near the harbour in Vestmannaeyjar. That year, the royal agent’s records indicate the construction team had already started building “skandters.” However, the precise nature of these structures is unclear. They might have fallen to destruction during the Turkish Raid in 1627 or deteriorated to the point of being ineffective for defence by then. Nonetheless, Jens Hasselberg, the king’s agent and the trade manager in Vestmannaeyjar, led the reconstruction of Skansinn between 1630 and 1637. Hasselberg also rebuilt the Danish trade and residential buildings that raiders had destroyed, fortifying them within Skansinn. The fortress featured a robust stone wall, two meters high and five meters thick, enclosing an area of about 32 meters by 15 meters. These fortifications earned admiration for their grandeur. Reverend Jón Daðason (died in 1676) praised it as the Southern Quarter’s most significant decoration.

Individuals skilled in the use of cannons and military equipment manned the cannons at Skansinn’s corners. In 1639, Jón Ólafsson, known for his voyages to India, oversaw the weapons’ maintenance and conducted weekly weapon training for the islanders. This duty continued well into the 17th century. However, by 1749, Vestmannaeyjar’s accounts noted that Skansinn contained old military equipment that had become obsolete.

Westman Islands Militia

In the mid-19th century, Andreas August von Kohl, a district commissioner and Danish army captain, established the Westman Islands Militia. As a fervent advocate for military discipline, the captain rallied men and boys into a well-organized force, focusing intensely on their training and weaponry.

This initiative essentially sought to bolster the Islanders’ confidence in their safety, particularly in the wake of fears sparked by the Turkish Raid. Cannons, dating back to 1586, were recommissioned for use, kick-starting the resumption of military exercises. The militia’s continuity waned rapidly after the dedicated captain’s death. Despite successors’ efforts, the military arrangement was eventually phased out between 1870 and 1880. Nevertheless, Skansinn continued to serve as a crucial signalling and flag-raising site for mariners, facilitating ship tracking.

The Second World War saw Skansinn become a stronghold for British military personnel and cannon batteries.

In celebration of a millennium of Christianity in Iceland, Norway presented Icelanders with a stave church thoughtfully sited on Heimaey. The Icelandic sagas recount how Hjalti Skeggjason and Gissur the White imported materials to the Islands and constructed a church.

Öskjuhlíð Military Remnants

Öskjuhlíð Hill and the adjacent Nauthólsvík Bay are sites where remnants from World War II are still visible. The British military occupied Iceland in 1940 partly to prevent a potential German invasion. They built aerial warfare facilities and constructed an air base between 1940 and 1942 known as Reykjavík Airport. This base supported aircraft that protected convoys transporting arms and supplies from America to Britain, crucial routes threatened by German submarines.

Key wartime relics in this area include

- Electric Generator Foundation: The location housed the air base’s electrical generator within a Nissen hut, measuring 35×8 meters, containing three or four diesel generators. The air base also received power from the city’s utility services.

- Fuel Tank Bund Walls: Just south of the emergency operations centre, three above-ground fuel tanks were protected by a 150-meter-long, 2-3-meter-high rock wall designed to stop fuel from spilling down the hillside in case of an attack. Nearby barracks accommodated British soldiers.

- Fuel Tank Pits: These four 15-meter-diameter pits were dug out for fuel storage, camouflaged with nets to protect against anticipated German raids. However, such an attack never occurred.

- Defence Battle Centre: An underground facility on Öskjuhlíð hill was crucial for Reykjavík and the air base’s defence, featuring a concrete structure with several small rooms shielded by rock or sandbags. It had two entrances and a secret tunnel with signal flags for communication. Only a fragment of the flagpole remains today.

- Pigeon Loft Foundation: The remnants of a two-story pigeon loft, approximately 20×3 meters in size, housed homing pigeons used for emergency communication by military aircraft.

- Gravel Roads: Constructed by the occupying forces, these roads connected different parts of the hill to essential facilities like the electrical generator, fuel tanks, and munitions storage.

- Fortifications: Initially built from sandbags and later more durable materials like rock and turf, these Icelandic forts have largely been reclaimed by nature. One fortification about 25 meters long is partly visible above the fuel tank pits.

- Underground Water Tanks and Bunkers: Scattered across Öskjuhlíð, these were primarily intended for firefighting and later repurposed for storing potatoes.

- Concrete Guard Post: Near the sea, this simple “pillbox” with gun slits is one of four remaining in the area, though such structures are becoming less common.

- Northwest Öskjuhlíð Fortification: This Icelandic fort is positioned between a bare cliff and a stone structure, adding to the area’s military historical landscape.

Reykjavík Airport

In the late 1930s, discussions were ongoing about establishing a permanent airport in Reykjavík, comparing its importance to that of Reykjavík Harbor. The Icelandic Aviation Association, founded in 1936 to pave the way for aviation, especially advocated for a viable airport where it currently is situated in Vatnsmýrin. Engineer Gústaf E. Pálsson designed Reykjavík Airport in 1937, proposing four runways aligned with Reykjavík’s main wind directions and partially determined by existing buildings around the airport.

The British occupation in 1940 accelerated the development of Vatnsmýrin, leading to the airport known today. Reykjavík was occupied by British forces on May 10, 1940, who began constructing a military airport in Reykjavík in early October 1940. The chosen location was similar to the proposed site for Reykjavík Airport. Upon realizing the British were serious about building an airport there, the Icelandic government decided to expropriate the land needed. Work on the airport began in early October 1940, with many Icelanders and soldiers involved in the construction, which included removing soil and replacing it with stone and red gravel. The airport officially opened on June 4, 1941.

Today, remnants of the occupation, such as airstrips, hangars, a few barracks, and the old control tower, along with artefacts in Öskjuhlíð, are the primary evidence of the occupation years in Reykjavík. Reykjavík Airport is Iceland’s hub for domestic flights and is one of the country’s four international airports.

Keflavík Airport and Base

Iceland’s biggest international airport, Keflavík Airport, was originally built by the American military during their occupation of Iceland during WWII.

During World War II, the United States military constructed the airport as an alternative to a smaller British airstrip at Garður to the north. This new facility comprised two distinct airfields, each with two runways, positioned merely 4 km apart. In 1942, Patterson Field, situated in the southeast, was inaugurated, albeit partially finished, and was dedicated to a young pilot who lost his life in Iceland. Meanwhile, Meeks Field, located in the northwest, commenced operations on March 23, 1943, and bore the name of George Meeks, another young pilot who perished on the Reykjavík airfield. He was the first of over 200 American soldiers to be killed in Iceland during the war. Following the war, Patterson Field was decommissioned. Still, Meeks Field and its adjacent facilities were handed over to Iceland, subsequently gaining the name Naval Air Station Keflavik after the adjacent town of Keflavík. In 1951, as part of a defence pact signed with the US on May 5, the American military reoccupied the airport.

Iceland served as a crucial link between Europe and North America during WWII. Hitler considered invading Iceland, but British and Canadian forces preempted this by occupying the island on May 10, 1940. The presence of British and Canadian troops, the strain on British forces, and the US’s concern for Atlantic shipping lanes eventually integrated Iceland into American defence plans.

The US Army Arrives in Iceland

In 1941, Britain, stretched thin by losses in Greece and North Africa, needed to repurpose the troops stationed in Iceland. Iceland, valuing its independence and heritage, was eager for the foreign troops’ departure, fearing that their presence invited conflict. Early discussions with the US about protection under the Monroe Doctrine were inconclusive, but German naval threats in the Atlantic prompted a reconsideration. The US destroyer USS Niblack engaged a German U-boat near Iceland in April 1941, marking the beginning of American military involvement around the island.

By mid-1941, the US agreed to replace British and Canadian forces in Iceland, requiring about 30,000 American troops. On July 7, 1941, the US finalized an agreement with Denmark (Iceland was then under Danish sovereignty) for the transition. The first US military unit, the 33rd Pursuit Squadron, landed in Iceland on August 6, 1941. A convoy transporting US Army troops departed in September 1941, arriving in Iceland without incident, marking the start of a significant American military presence on the island.

Iceland Base Command

In 1941, there was unanimous support within the Army Air Forces, GHQ AF, and the Iceland Base Command for constructing a heavy bomber field in Iceland. After favourable site and soil surveys in November and December 1941, it was agreed to start construction near Keflavik for an airfield suitable for heavy bombers.

Concurrently, the commander of the Iceland Base Command’s air forces initiated the construction of a new fighter field as part of the defence mission. This field was later integrated as a satellite field to the bomber project. By the time civilian construction teams arrived in May, significant progress had been made.

The Army Air Corps Ferrying Command’s need for a transit ferrying airfield in Iceland and the presence of bomber bases in England led to the Ferrying Command overseeing the Keflavik airfields. Consequently, a long-range transport airfield and a fighter airfield for Iceland’s air defence were built.

Construction of Meeks Field began on July 2 by the Army Corps of Engineers. It was continued by a Navy Seabee unit. The first landing, by a B-18 Bolo bomber, occurred on March 24, 1943. By July 1943, all major construction, including four 6,500 ft runways, was completed, making Meeks the Iceland Base Command headquarters and a key point for aircraft ferrying between the US and the UK.