When discussing Iceland during World War II, most people think of its strategic importance and the presence of Allied forces. The story of Icelandic Nazis and those who were tragically sent to Nazi concentration camps is often overlooked. This post delves into that lesser-known history. Uncovering the Icelandic Nazis and the harrowing experiences of Icelanders imprisoned in Nazi camps.

On 10 May 1940, Iceland’s isolation was shattered as British forces launched Operation Fork, swiftly occupying the island to prevent Nazi Germany from seizing it as a strategic base. The occupation carried out without resistance from the Icelandic people, became pivotal in defending the British Isles. While Iceland’s involvement in World War II may not always take centre stage in history books, the occupation profoundly impacted the nation’s development and its future on the global stage.

Be sure to check out our previous post for a deeper dive into the broader context of Iceland in World War II.

Check out our Walk With a Viking Tour and Private Viking Age Walking Tour to learn more about Iceland.

The Icelandic Nationalist Movement

The Icelandic Nationalist Movement was founded in 1933, inspired by German Nazism, following the Gúttóslagur riot on November 9, 1932. At the time, Iceland struggled with high unemployment during the Great Depression, and the city council had decided to cut wages for public relief workers. After a meeting in Gúttó, where the decision was announced, riots erupted between workers, backed by communists, and the police. The workers won, and the wage cuts were abandoned.

Far-right members of the Independence Party were outraged by this “lawlessness,” believing their party was too weak to oppose communism. Disgruntled Progressives and newcomers to politics, influenced by German Nazism and Hitler’s recent rise to power, joined forces to form the Nationalist Movement.

The party’s main goals were to protect Icelandic culture and preserve the white race. They called for restrictions on immigration, allowing only highly skilled professionals deemed necessary. However, Iceland’s society in the 1930s was highly homogenous, with few foreigners other than Danes. Lacking a significant Jewish population to target, as in Germany, Icelandic nationalists primarily directed their efforts against communism.

The party never gained enough support from voters to secure a seat in parliament. Its closest attempt came in 1937, when it ran in the Gullbringu- and Kjósarsýsla district, earning 4.9% of the vote—still not enough to win a seat. The movement gradually faded over the next three years and eventually dissolved entirely. But that doesn’t mean that nazism died with it.

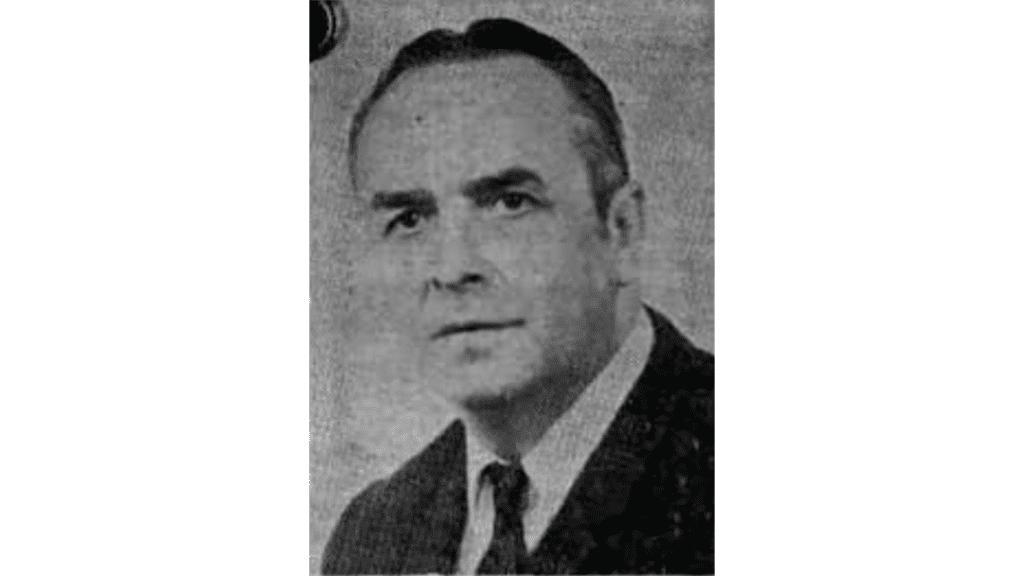

Agnar Kofoed-Hansen: Icelandic Nazi Sympathiser and Chief of Police During WWII

Agnar Kofoed-Hansen, born on 3 August 1915, was a pivotal figure in Iceland’s wartime history. He was known for his aviation career and controversial role as Reykjavík’s Chief of Police during World War II. Born in Reykjavík, Agnar pursued aviation studies in Denmark, Norway, and Germany, where he was heavily influenced by Nazi ideology, particularly regarding the pseudoscience of hereditary criminality. He co-founded various aviation organizations in Iceland, including the Svifflugfélag Íslands (Icelandic Glider Club) in 1936 and Flugfélag Akureyrar (Akureyri Aviation Society) in 1937.

In 1939, at just 24 years old, Agnar was appointed Chief of Police in Reykjavík by Hermann Jónasson, the Minister of Justice. That same year, Agnar was sent on an observation tour to Copenhagen and Nazi Germany. There he was deeply impressed by German research into eugenics and criminal behaviour, further solidifying his alignment with fascist ideologies.

Nazi Sympathies and Controversial Role During WWII

In 1939, Prime Minister Hermann Jónasson tasked Agnar’s office with establishing the “Surveillance Division” within the police’s Foreign Monitoring Unit. This department was notorious for scrutinizing foreigners and local Icelanders.

He maintained that his visit to Germany and Denmark was focused solely on genetics, denying any connection to learning about Nazi ideology. However, the real motivation for establishing the division was driven by the growing influence of both Nazism and communism in Iceland, especially after the Gúttóslagur riot in 1932. Years later, in 1976, the secret documents, gathered through extensive surveillance and wiretapping, were deliberately burned in a punctured oil barrel to conceal the embarrassing involvement of key individuals.

Agnar’s most controversial involvement came during what is now referred to as the “Circumstances” in Iceland—a period during the Allied occupation when relationships between Icelandic women and foreign soldiers caused social unrest. Agnar, alongside Prime Minister Jónasson, orchestrated a moral investigation spearheaded by former head nurse Jóhanna Knudsen. Her mission was to document and discredit over 500 women involved with Allied troops. This cast suspicion on their morality and even accused many of prostitution. Agnar, as Chief of Police, oversaw these efforts, which sought to rally public opposition to these relationships and pressure lawmakers into taking action.

Check out our dedicated post on the topic for a deeper look into the “Circumstances”.

Post-War Career and Legacy

After the war, Agnar remained influential in Iceland’s aviation sector. From 1947 to 1951, he served as the Director of National Airports before being appointed the Director of Civil Aviation in 1951, a position he held until his death in 1982.

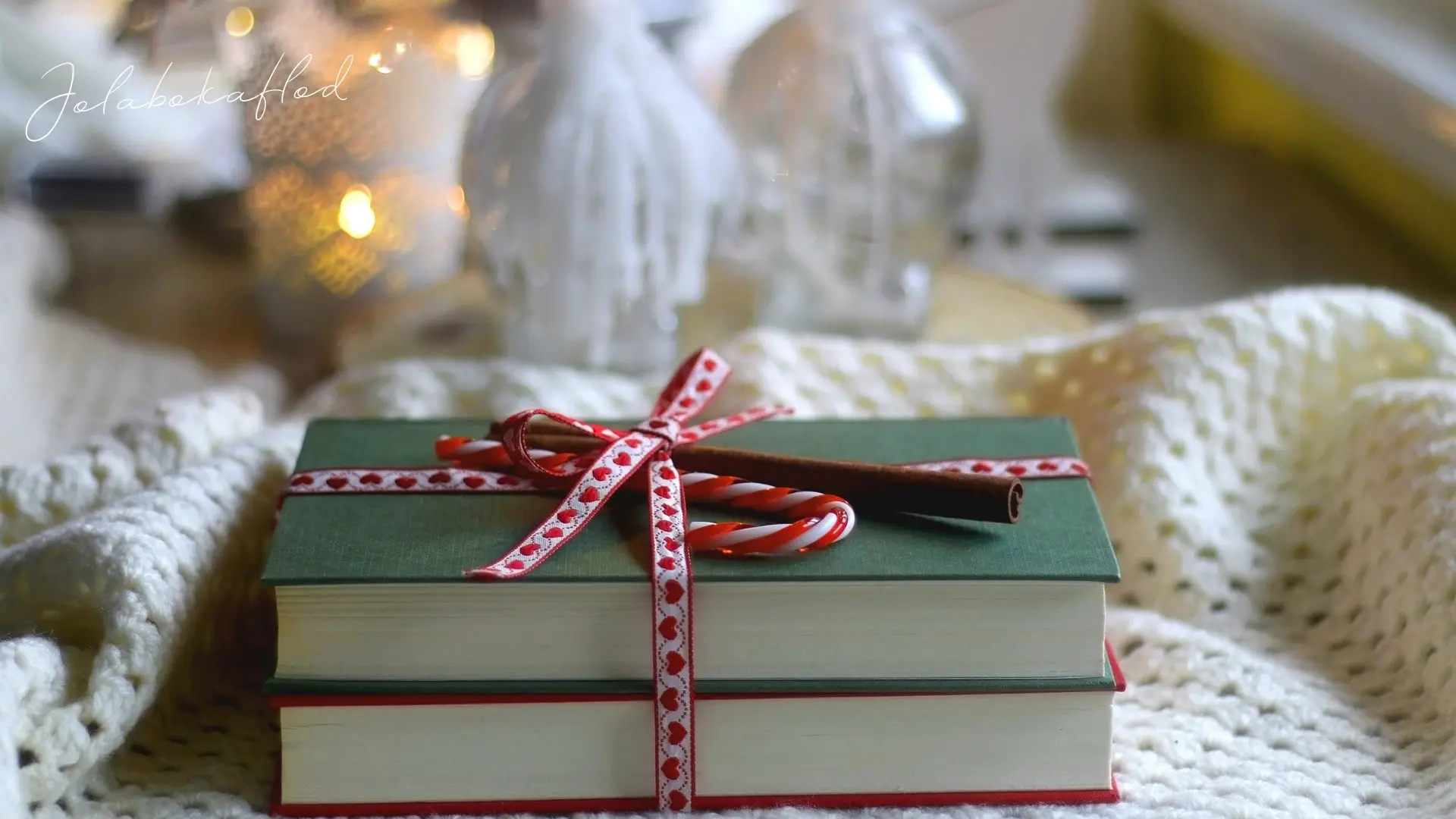

Björn Sv. Björnsson: The President’s Son

Björn Sv. Björnsson was born on 15 October 1909 and the son of Iceland’s first president, Sveinn Björnsson, led a life shaped by his fascination with Nazi ideology. After graduating from Menntaskólinn í Reykjavík in 1930, Björn moved to Germany, working for Eimskip in Hamburg. He had planned to study music, but with his fiancée María expecting their first child, Björn focused on work instead. The couple had two daughters, Hjördís and Brynhildur Georgía, before divorcing in 1937.

Nazi Affiliation and Military Service

Björn was drawn to Nazi ideology when the party rose to power in Germany. In 1941, he eagerly applied to join the Waffen-SS, declaring his Aryan heritage with pride. He served in the 5th SS Panzer Division Wiking and later in SS-Standarte Kurt Eggers as a correspondent on the Eastern Front. Björn’s broadcasts from the front aimed to depict Nazi Germany as a saviour against the Soviet Union, a message tailored for Icelandic audiences.

After being promoted to Unterscharführer, he attended officer school in Bad Tölz and later worked in German propaganda in Denmark. His radio appearances made him infamous, and he was awarded the Iron Cross 2nd Class in 1945.

Post-War Life and Return to Iceland

Following Germany’s surrender, he was among the Icelandic nazis that were captured by Danish partisans. He was held for over a year before being mysteriously released, possibly due to intervention by his mother. He was smuggled back to Iceland but faced harsh criticism, with author Halldór Laxness calling him “one of the worst Icelandic men.”

Björn remarried and briefly moved to Argentina before returning to Iceland, where he worked at Keflavík Airport and later in Germany. In 1989, he published his memoirs, Ævi mín og sagan sem ekki mátti segja (My Life and the Story That Could Not Be Told). Björn died in 1998 in Borgarnes, marking the end of a controversial life tied to Nazi Germany.

Ólafur Pétursson: One of the Infamous Icelandic Nazis

Early Life and Involvement with the Nazis

Ólafur Pétursson, born in 1919, was the son of Pétur Ingimundarson, the fire chief of Reykjavik. Before World War II, Ólafur left Iceland to study in Norway. In August 1940, he began working with German military intelligence. By 1941, he had fully committed to Nazi collaboration. He infiltrated the Norwegian resistance and provided critical information that led to the arrest and death of many resistance fighters.

Betrayal and the “Icelandic Executioner”

Ólafur’s betrayal earned him the notorious nickname “The Icelandic Executioner.” He gained the trust of Norwegian resistance members, only to pass their details to the Nazis. His actions sent several people to concentration camps, and some never returned.

Leifur Müller, an Icelandic resistance member who was sent to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp, recounted in his autobiography Býr Íslendingur hér? that Ólafur had likely arranged his arrest after inviting him and another resistance member to a coffee gathering in Norway:

“While high-ranking Nazis like Holmboe were sentenced to eight years in prison, Ólafur Pétursson was sentenced to twenty. The court clarified that his actions were criminal, deeply reprehensible, and a breach of trust.”

Capture and Post-War Trial

As Nazi Germany began to collapse, Ólafur fled to Denmark. When attempting to return to Iceland, he was arrested by the British military. After the war, Norwegian authorities sentenced him to 20 years of hard labour for espionage, with the prosecutor initially seeking the death penalty. Despite this, Icelandic authorities intervened, leading to Ólafur’s release and return to Iceland in 1947. Just months after his sentencing, his freedom angered many Norwegians, especially those in Bergen, where his betrayals had the greatest impact.

Return to Iceland and Legacy

Back in Iceland, Ólafur resumed his life, establishing an auditing firm and playing a role in the violent Anti-NATO riots in Austurvöllur in 1949. His actions during the war were widely condemned, and his legacy remains one of betrayal and controversy. Icelandic author Halldór Laxness even described Ólafur as “one of the worst Icelandic men who ever existed.”

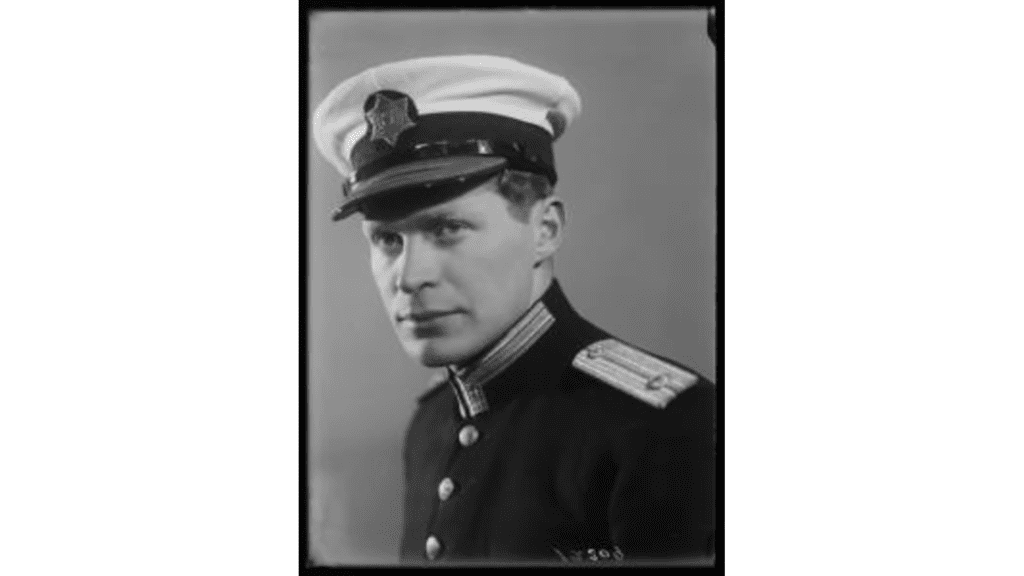

Egill Holmboe: From Norwegian Diplomat to Icelandic Nazi Sympathiser

Early Life and Diplomatic Career

Egill Holmboe, born in Norway on 24 April 1896, led a life that spanned both countries and ideologies. Before World War II, Holmboe served in the Norwegian Foreign Service and held the position of vice-consul in Reykjavik. In 1939, just before the outbreak of the war, he returned to Norway.

Holmboe was a member of the Norwegian Nazi Party. During the German occupation of Norway, he served as a senior official in the Ministry of the Interior under Vidkun Quisling’s puppet government. Notably, Holmboe acted as Adolf Hitler’s interpreter during Knut Hamsun’s visit to Hitler’s residence at Berghof in Austria in 1943.

Betrayal and Accusations

Holmboe’s past became even more controversial due to allegations made by Leifur Müller, an Icelander who was arrested while trying to escape from Norway to Sweden and later sent to a Nazi concentration camp in Germany. Müller suspected that Holmboe, who had been a close friend of the Müller family during his time in Iceland, had betrayed him to the Germans, leading to his arrest.

Post-War Sentencing and Life in Iceland

After the war, Holmboe was sentenced to several years in prison in Norway for his collaboration with the Nazi regime. 1953, following his release, he relocated to Iceland, adopting Egill Fálkason after being granted Icelandic citizenship in 1955. He married Sigríður, the daughter of Iceland’s National Museum curator Matthías Þórðarson. Holmboe worked with the U.S. military at Keflavík Air Base for much of his later life.

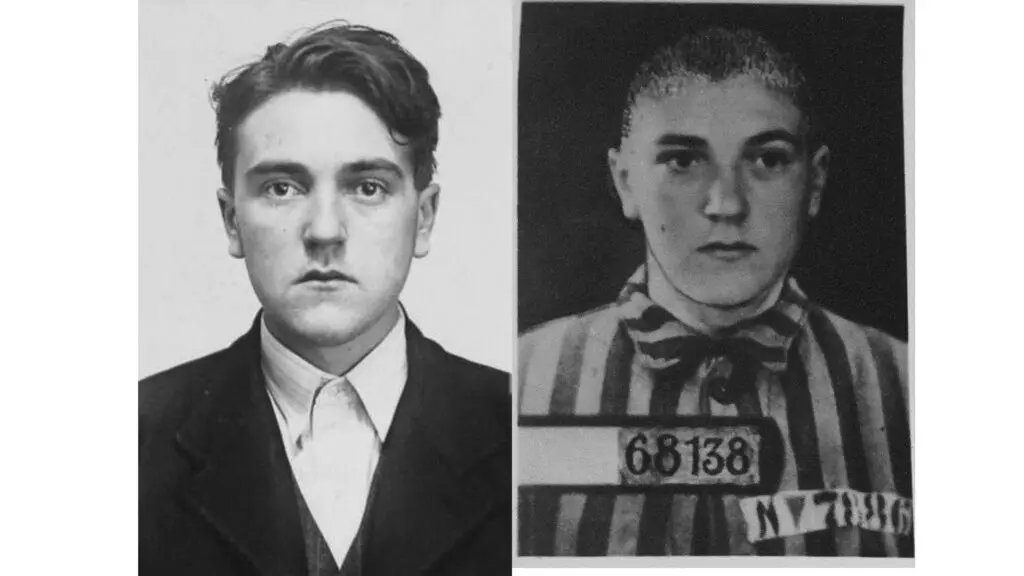

Leifur Muller: Icelandic Survivor of Nazi Concentration Camps

Early Life

Leifur Miller, born on 3 September 1920, came from a well-off Icelandic family with Norwegian roots. His parents, Lorentz H. Müller and Marie Bertelsen ran a successful business in Reykjavik. Leifur attended Landakotsskóli and later Menntaskólinn í Reykjavík. He struggled with shyness, stuttering, and his imperfect Icelandic, as his family mostly spoke Norwegian at home. After graduating in 1937, he was sent to study business in Oslo, Norway, and later in Copenhagen before returning to Norway in 1939.

Arrest and Imprisonment

After the German occupation of Norway in 1940, Leifur tried to escape to Iceland. In 1942, with help from Icelandic diplomat Vilhjálmur Finsen, Leifur secured a place at a school in Sweden as part of an escape plan. However, he confided his intentions to his acquaintance, Ólafur Pétursson, and family friend Egill Holmboe, both Nazi sympathizers. Shortly after, on 21 October 1942, the Gestapo arrested him. He was 22 years old.

Initially, Leifur expected a short sentence, but in January 1943, he was transferred to Grini concentration camp near Oslo, where he met fellow Icelander Baldur Bjarnason. He suffered greatly from malnutrition and illness, but a bout of pneumonia likely saved him from being sent to Sachsenhausen immediately. In June 1943, he was transported to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp in Germany, a brutal labour camp notorious for its high death toll.

Life in Sachsenhausen

Leifur arrived at Sachsenhausen in June 1943, where he was assigned prisoner number 68138 and forced into hard labour. The Red Cross packages provided to Norwegian prisoners helped him survive. He later managed to secure a job as a nurse’s aide, which prolonged his stay in the infirmary. His survival depended heavily on this work and the ability to exchange Red Cross food for favours.

In early 1944, Leifur was placed back into hard labour but met another Icelander, Óskar Björgvin Vilhjálmsson, who died shortly after their meeting. Leifur’s condition continued to deteriorate until, in March 1945, the Swedish Red Cross, led by Count Folke Bernadotte, intervened. Leifur and other Scandinavian prisoners were transported to Sweden in the famed “White Buses,” saving their lives.

Post-War Life and Legacy

After the war, Leifur returned to Iceland, where he wrote Í fangabúðum nazista (In Nazi Concentration Camps), detailing his harrowing experiences. Though he survived, Leifur struggled with the physical and emotional scars of his imprisonment. He later changed his last name to “Muller” to avoid association with Germany. He suffered from health problems linked to his time in the camps, including tuberculosis.

In the 1950s, Leifur testified in Norway against Egill Holmboe, who he believed betrayed him to the Nazis, but Holmboe was acquitted of those charges. Leifur married Birna Sveinsdóttir in 1951 and had five children. He continued to work in his family’s business until health issues forced him to retire. Leifur passed away on 24 August 1988 at the age of 67.

Explore our previous posts for more on Iceland’s involvement in WWII, including how the occupation shaped the country’s future.