May 10, 1940—a date etched in the collective memory of Icelanders as a fateful day that forever altered the course of their history. In the peaceful early hours, thunderous engines shattered the serene Icelandic skies, an unusual disturbance in a land where airports were yet to dot the landscape, and air flights remained a rare spectacle. The island’s inhabitants, still awaiting their sovereign status, were at a crossroads laden with uncertainty. Had the dreaded Nazis, fresh from their invasion of Denmark just a month prior, finally cast their gaze upon Iceland?

A palpable tension gripped the nation, casting shadows of doubt and apprehension. But as the hours ticked on, a collective exhale swept the Icelandic landscape. The intruders in the sky were not the feared Nazis but the British—a welcome relief, indeed.

As the world plunged into the chaos of war, Iceland, nestled in the turbulent waters of the North Atlantic, assumed a unique position. Its strategic location inevitably drew it into the global conflict. Yet, its geographical isolation shielded it from the direct horrors of warfare. It was a time when the nation stood at the precipice of destiny, and an enthralling narrative unfolded—a tale of intrigue, controversy, and just a touch of scandal.

In a population of merely 120,000 souls, Allied troops—peaking at nearly 50,000 strong in 1943—gave rise to an exaggerated sense of peril. It was within this backdrop that the Reykjavík Chief of Police and the multifaceted Hermann Jónasson, who donned the dual hats of Prime Minister and Minister of Justice, embarked on a mission of extraordinary proportions. Their goal? To scrutinize the moral conduct of Reykjavík’s women and spark public outrage over their connections with foreign soldiers. A strategic manoeuvre aimed at swaying the members of parliament and other ministers into action set the stage for a riveting drama.

What is ‘The Circumstances’?

Ástandið, a term that translates to “the condition”, “the situation”, or “the circumstances” in English, encapsulates a chapter of the history of Iceland during World War II that remains both fascinating and controversial. It refers to the profound and often unspoken influence that Allied troops had on Icelandic women during the war years. As Iceland became a critical military outpost in the North Atlantic, it experienced a transformation far beyond geopolitical significance. The arrival of foreign troops, mainly British and American, brought a cultural exchange that left an indelible mark on the Icelandic society of the time.

We have already told you about how Icelanders received the British, so head over there to delve deeper into the arrival of British troops in Iceland.

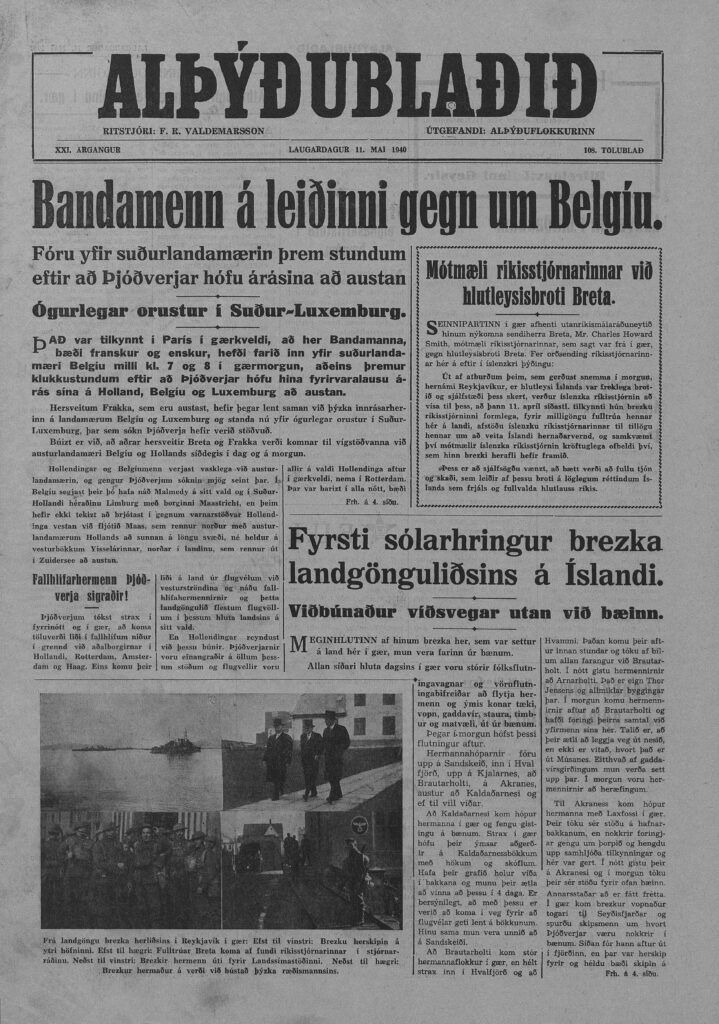

The arrival of the army made headlines in the Alþýðublaðið newspaper the very next day. The article included a brief interview with the police officers stationed at the harbour to oversee the proceedings. While there were not many protests, one particular concern did emerge – the perceived overeagerness of some Icelandic girls in their interactions with the soldiers. The newspaper issued a warning, suggesting that due to this issue, the soldiers had been excessively friendly with the women. They called for an increase in police authority to address this matter.

Discussion of ‘The Circumstances’ began instantly

So, within just a day, the discussion regarding the ‘ástand’ began to unfold. People engaged in conversations, and newspapers sporadically reported on the topic. Most of these reports condemned women involved with the troops, labelling them as traitors and bimbos.

It became increasingly evident that action needed to be taken. Consequently, in the fall of 1940, the then-Prime Minister, Hermann Jónasson, convened a meeting with all the country’s school principals. They discussed the issues and collectively drafted an ‘Address to the Nation,’ primarily directed toward the parents of children attending the country’s schools. This address emphasized the importance of caution and prudence in troop interactions. It also stated that entertainment organized by school students would be exclusively for them, and restrictions would be imposed on the outdoor activities of urban children. They were advised to minimize contact with the soldiers whenever possible.

Icelanders Try to Limit Contact with Military

In October of the same year, another meeting was held by fourteen youth organizations in Reykjavík. At the end of the meeting, a resolution was passed which stated that all the activities of the youth associations, whether it be sports practices, dances or scout meetings, should occur within Icelandic associations. The troops would not be allowed access to them. Modesty in dealing with the army was encouraged, but otherwise, to have as little contact with them as possible. However, at that time, many Icelanders had already found employment with the army, whether building military bases and roads or doing laundry for them. It was as if a Pandora’s box of opportunities had been opened, with many entertainment venues and restaurants opening simultaneously. Therefore, it was difficult at this point to limit Icelanders’ contact with them.

Icelandic Boys Took Matters Into Their Own Hands

While the occupation forces frequently hosted balls and dinner parties. They sometimes even extending invitations to the townspeople; opinions on these events varied. So, when the troops in Akureyri went a step further by borrowing the town’s hall for dance and inviting their ‘friends,’ a group of high school boys stationed themselves outside the venue, meticulously recording the girls’ names who entered.

The following day, this list of 65 girls appeared in the newspaper Verkamaðurinn (The Labourer). Not everyone applauded the high school boys’ actions; in fact, the headmaster of Akureyri High School admonished them, warning of consequences if such incidents recurred. However, when the troops organized another dance in Akureyri, only 40 girls attended, suggesting that the boys’ antics had achieved their intended effect.

Nonetheless, opportunities for soldiers and Icelandic girls to mingle were abundant, with entertainment venues, hotels, and pubs serving as meeting grounds. These encounters occasionally sparked jealousy among Icelandic boys, leading to occasional conflicts.

The Arrival of the Americans and a Moral Dilemma

On July 7, 1941, a pivotal moment dawned as the American army landed on Icelandic shores, ready to relieve the British occupation forces. In the eyes of many, these American soldiers appeared tidier, more attractive, and notably wealthier than their British counterparts. Their presence cast a new light on the local entertainment scene and shops, making them prominent figures in the Icelandic landscape. However, as the excitement swirled, so did rumours of prostitution.

Growing concerns reached a tipping point, prompting the Director of Health to write to the Ministry of Justice. Within its lines, the police’s belief was starkly conveyed—several girls, aged between 12 and 16, were believed to have entered into prostitution. It was a troubling revelation that demanded swift government action. One idea floated during these deliberations was the military’s potential importation of prostitutes for its soldiers. This proposal loomed but was never put into practice.

Instead, a decision was made—a committee was to be formed. The Reykjavík Chief of Police, in collaboration with Hermann Jónasson, orchestrated the appointment of a former head nurse, Jóhanna Knudsen. Her mission? To delve deep into the moral fabric of Reykjavík’s women, uncovering the intricacies of their relationships with the soldiers. The ultimate goal was to ignite public opposition to these relationships. Thereby exerting pressure on members of parliament and other ministers to take action.

However, within this political landscape, a nuanced scepticism prevailed. The Prime Minister, a member of the centre-left Progressive Party, harboured doubts about the conservative Independence Party and the Labour Party’s willingness to engage in legislative action. As the stage was set for Jóhanna Knudsen’s investigation, Iceland was at a crossroads. It was grappling with the moral implications of its wartime alliances.

A Morality Committee and a Nationalistic Twist

Jóhanna Knudsen delved deeply into people’s private lives during her investigations, scrutinizing at levels unprecedented in Icelandic police history. She meticulously documented over 500 women’s names suspected of troops’ relationships, recording various personal details. Her approach was marked by her distinct morality interpretation, intense nationalism, and a tendency to view Icelandic women’s interactions with troops through a sexual lens. This resulted in an alarming exaggeration of perceived immorality and prostitution, even involving teenagers.

Amid this fervour, Prime Minister Hermann Jónasson made a pivotal move in 1941 by establishing the “Morality Committee.” Three young male academics were tasked with investigating issues arising from these relationships and suggesting solutions. However, their report, when revealed, closely mirrored Jóhanna Knudsen’s conclusions, leading to doubts about its authenticity.

The Chief of Police, despite his relative lack of experience, then made allegations against an additional 2,000 women. He claimed that these women had engaged in inappropriate interactions with military personnel. This assertion appeared highly implausible, suggesting a startlingly high incidence of such alleged involvements, approaching one in three women between the ages of 15 and 35 being romantically connected to Allied troops.

Ironically, amidst these accusations, the troops themselves had voiced grievances. They lamented the aloofness maintained by most Icelandic women, a stark contrast to the prevailing narrative. Jóhanna Knudsen’s recently declassified registry further unveiled the police’s lack of substantial evidence for their sweeping allegations.

Juvenile Supervision Took Centre Stage

While the Morality Committee’s report briefly stirred something akin to mass hysteria, a closer examination reveals that both the Committee and the police faced harsh criticism from both men and women. This critical perspective, largely overlooked in historical accounts, adds depth to the unfolding narrative.

In late 1941, draft legislation on juvenile supervision took centre stage. Hermann Jónasson presented it to members of parliament from the coalition parties, with the draft being primarily composed of a committee consisting of prominent women. Despite these meticulous preparations, the all-male Althing rejected the draft. Yet, in December 1941, the Minister took matters into his own hands. Issuing a provisional law based on the draft legislation, albeit with amendments. This law extended the authorities’ power to supervise young people up to the age of 20, even though the age of majority was 16. It also established reformatory institutions and juvenile tribunals to address issues like promiscuity and various other delinquencies.

Clandestine Surveillance

However, when the Althing convened to discuss the provisional law in 1942, the Coalition’s members made revisions, including reducing the maximum age of supervision to 17. Hermann Jónasson’s staunch opposition to these amendments left him seemingly isolated, and his government faced collapse.

As the echoes of Jóhanna Knudsen’s exhaustive investigations reverberated across Iceland. The stage was set for an unfolding drama that would lay bare the complexities of society during the “Circumstances.” From April 1942 to October 1943, a juvenile tribunal in Reykjavík grappled with a deeply divisive issue.

Fourteen young girls found themselves confined to a remote reformatory school. At the same time, another 26 were dispersed to separate farms, all due to allegations of promiscuity. The juvenile tribunal’s decisions drew heavily from police reports generated by a newly established juvenile supervision department, helmed by Jóhanna Knudsen herself. This clandestine agency operated with an air of secrecy, leaving a lingering sense of unease.

But branding these girls as criminals was a gross oversimplification of their plight. In many cases, their struggles were rooted in complex social circumstances, often compounded by instances of sexual abuse perpetrated by both Icelanders and foreign soldiers. Shockingly, the perpetrators seemed to escape the clutches of justice.

Reformatory Schools Abolished

Enter Einar Arnórsson, a figure of great legal authority and now the Minister of Justice in a non-parliamentary government. In October 1943, he dissolved the reformatory school, recognizing that it did more harm than good. The juvenile tribunal met a similar fate as it was abolished, liberating these girls from the burdensome weight of its judgments.

Arnórsson’s actions bore the marks of empathy and compassion. He viewed the juvenile supervision law as deeply flawed, tainted by nationalistic, patriarchal, and discriminatory undertones. He rejected the prevailing narrative that portrayed women as threats to Icelandic culture through their relations with foreign troops.

With the dismantling of the juvenile supervision law, the municipal child protection committee of Reykjavík assumed responsibility for addressing juvenile delinquency issues in the city. Their first demand? The dissolution of the police’s juvenile supervision department signaling a significant shift in approach.

However, these changes did not occur without resistance. Prominent women, church leaders, educators, officials, and intellectuals united to strengthen the juvenile supervision law. They aimed to protect young lives from foreign military influences during wartime turmoil.

Unspoken Realities – Hidden Lives

During the tumultuous years of Iceland during World War II, the country found itself at the crossroads of history. While attention has focused on challenges faced by women and girls during the “Circumstances,” there’s another silenced chapter that deserves acknowledgement.

It was a time when homosexuality was hardly discussed openly in society. Many of the men involved in those relationships hadn’t realized their sexual orientation until they found themselves in close quarters with the foreign soldiers. Naturally, these experiences remained concealed, and those involved often felt isolated in their emotions.

For some gay men in Iceland, the presence of foreign soldiers presented both opportunities and challenges. Engaging in relationships with soldiers often meant maintaining the utmost discretion. Soldiers themselves rarely disclosed their sexual orientation, as it could lead to their expulsion from the military.

While romantic relationships did exist, many encounters were brief, one-time occurrences. Some young men, like Þórir Björnsson, found themselves in secretive relationships, concealing gifts from their partners and the truth from their families. These concealed liaisons offered excitement, even a sense of adventure, amid wartime chaos.

A Hidden Voice

Þórir Björnsson’s story provides a glimpse into the experiences of gay men during the “Circumstances.” He was a young man of 15-16 years old who found himself in a six-month relationship with a doctor. The doctor visited him at the same location weekly, offering gifts that Þórir had to hide from his mother. Þórir’s experiences during that time were a closely guarded secret.

Later in life, Þórir joined the Canadian army, but like many others, he could not openly express his homosexuality. As the war ended, some of his friends married and started families, and the memories of their wartime experiences were buried deep, never to be spoken of again.

Særún Lísa Birgisdóttir, a dedicated folklorist, played a pivotal role in preserving and researching this hidden chapter of Icelandic history. She completed her BA and Master’s on this topic, diving deep into the untold stories of those who lived through the “Circumstances.”

Þórir Björnsson was a key source for Særún, offering insights into gay men’s lives in that era. Though Þórir has passed away, his stories live on through Særún and others, shedding light on Iceland’s hidden past.

Today, the significance of this aspect of the history of Iceland during World War II is being recognized and shared. Scholars like Særún have worked tirelessly to preserve these stories. Researching the lives of the young men who experienced the “Circumstances.” As we reflect on this chapter in Icelandic history, we see that these hidden lives are a crucial part of our past. We shouldn’t forget this history but should acknowledge and remember it in our nation’s journey.

Sources:

Þór Whitehead: Ástandið og yfirvöldin: stríðið um konurnar 1940-1941. Saga: Tímarit Sögufélags 2013 LI: II

Bjarni Guðmarsson og Hrafn Jökulsson. Ástandið (Tákn bókaútgáfa, 1989)