Ah, Skólavörðustígur! Stretching from the historic Skólavörðuholt to where Laugavegur meets Bankastræti, this street is nothing short of iconic. Tracing its history is like thumbing through the pages of a novel, where every chapter reveals a new tale of cultural significance, an architectural wonder, and colorful transformation. Join us on this journey as we stroll down the iconic Skólavörðustígur, from its origins surrounding the storied School Cairn to its contemporary metamorphosis into the lively Rainbow Street.

The School Cairn Path – Strange Name but Logical

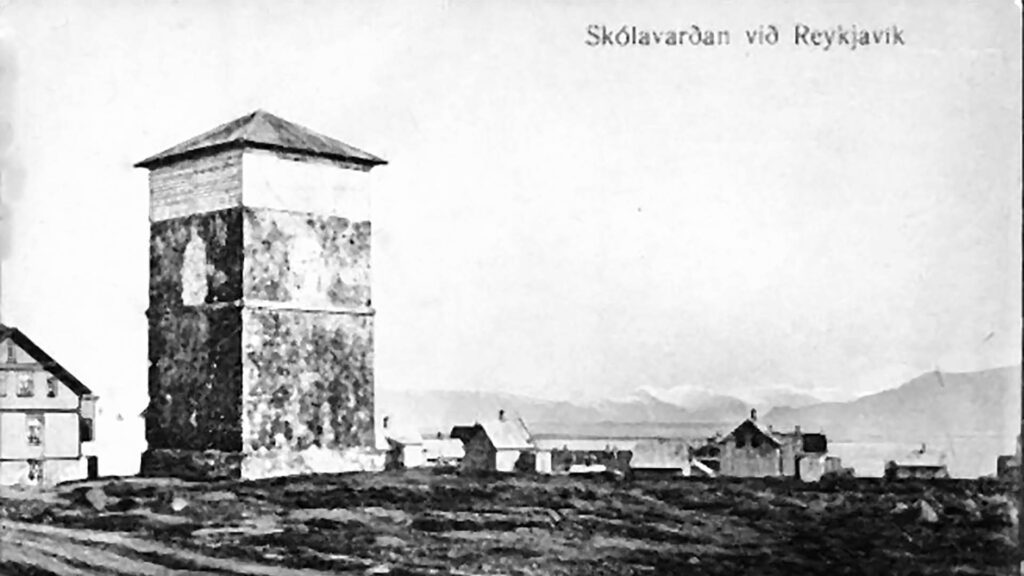

The name? Oh, it hails from the School Cairn (Skólavarða), a handiwork of students from the Hólavallar School. You can almost picture them years ago, building it near where Hallgrímskirkja Church stands proud today.

Ever noticed the Leif Eiríksson statue at Skólavörðuholt? That’s the very spot where the school cairn once stood tall. Inspired by the old-school custom from Skálholt, some adventurous students decided to spruce up Reykjavík with its very own cairn at Arnarhólsholt. After the cairn was built, the hill’s name changed to Skólavörðuholt.

Knud Zimsen, our mayor from 1914 to 1932, painted this delightful memory: “Imagine a bright spring Sunday in 1793. Hólavallar School boys embarked on a mission in their charming knee-length tunics and pants. Their path took them across the Lækur, where Lækjargata Street is, up to the picturesque Arnarhólsholt. There, stone by stone, they built a majestic school cairn. Reykjavík, then only seven, got its school mark!”

Alas, over time, this emblematic cairn met its end. But in 1868, with a dash of creativity from Sigurður Guðmundsson and the craftsmanship of Sverrir Runólfsson, a revamped cairn rose again, standing a mighty 15 cubits high.

Great Views of Reykjavik – If You Were Lucky

Nobel laureate Halldór Laxness once mused about it, “The School Cairn, crowned where Hallgrímskirkja is today, was an opulent four-sided marvel. Climbing it? Just five pennies – if you could get the key from its guardian.”

By 1931, change was in the air again. The cairn made way for Leif Eiríksson’s statue in 1932. Today, a lovely replica of the school cairn nestles by the church, right next to the Einar Jónsson Museum. A testament to Reykjavík’s rich history and a nod to those ambitious students from long ago.

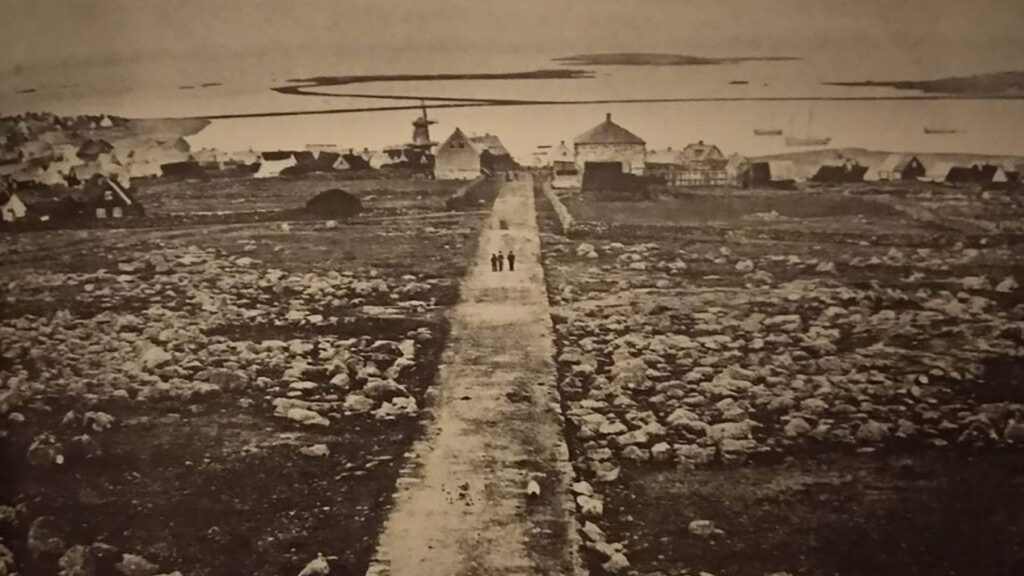

Skólavörðustígur was envisioned as a recreational path, and to reduce maintenance costs, horse traffic was prohibited. This decision led to challenges, particularly in stone transport, such as during the construction of the stone farm at Skólavörðustígur 11. Around 1870, a road was initiated from the school cairn to Öskjuhlíð and was completed in the fall of that year.

Rainbow Street: Downtown Reykjavík’s Colorful and Pedestrian-Friendly Gem

Located in the heart of downtown Reykjavík, Rainbow Street is much more than just a street. It’s a bold and colourful symbol of the city’s vibrant spirit and progressive values.

At the intersection with Bergstaðastræti, visitors are greeted by a striking view as the street turns into a rainbow, with bold stripes of red, orange, yellow, green, blue, and violet painted on the asphalt. The colours continue upwards, with nearby buildings reflecting the same multicoloured design on their facades.

Designed for pedestrians, Rainbow Street is a popular spot for strolling, window shopping, and relaxing at local cafés.

A Street of Art Galleries, Boutiques and Cafés

Skólavörðustígur, which leads directly to the iconic Hallgrímskirkja, has evolved from a simple road into a lively hub of culture and commerce. The street is now home to art galleries, boutiques, craft stores, and cozy cafés, all contributing to its vibrant atmosphere.

Read more about visiting Iceland as an LGBTQIA+ person here. Your Friend in Reykjavik also offers private LGBTQIA+ City Walks. Pride Week is held in Reykjavik the week after the first weekend of August. Every year a section of road is temporarily painted in pride colours. In 2023, Vegamótastígur (between Skólavörðustígur and Laugavegur shopping street) was painted in the Trans flag colours.

Skólavörðustígur 4 – The First Stone Building by Icelandic Stonemasons

In 1883, a milestone was reached when a stone house was built at Skólavörðustígur 4. Hewn from stone, it was the first of its kind crafted solely by Icelandic stonemasons. Magnús Guðnason, who learned stonemasonry while working on the Parliamentary Building, was its original owner. He passed away in 1961, around the age of 90. Initially a residential building, it housed four families or 12 people in 1885. In the 1930s, the lower floor became a shop, and from the 1950s onward, it was used entirely for commercial purposes. The building’s appearance changed significantly in the summer of 1988, with the upper floor serving as a showroom for a period.

The Jail on Skólavörðustígur

In 1871, a plot on Skólavörðustígur was designated for a penitentiary. This large, neoclassical structure, built with piled stones, was completed in 1873 by Danish craftsmen. Master carpenter Klentz commissioned the project, but F A Bald, who oversaw the Parliament building, supervised the construction.

The Penitentiary served a multifaceted role, not just replacing the so-called “Black Hole” in the Internal Legal Court (Austurstræti 22 – prisoners were housed in the attic of the small house). The upper floor hosted the Internal Legal Court from 1873, featuring a divided courtroom with litigants and judges seated separately. The court’s last session was on December 22, 1919, when the Supreme Court assumed its responsibilities until 1947, when the new Supreme Court Building was established at Lindargata 1. The Penitentiary continued as a prison until 2016 and is now being renovated for public access.

The upper floor was also a civic hub, hosting town council meetings from 1873 to 1903, after which they moved to Góðtemplarahúsið (Templarasund 2). Reykjavík’s district court was held there for decades until it was moved to Túngata 14 (Hallveigarstaðir). The prison cells occupied the lower floor, and the yard’s well was the primary water source. Initially surrounded by a wooden fence, it was replaced by a grey stone wall before 1900, later augmented with concrete.

A 1967 plan intended to demolish the prison to create better city center connections by linking Grettisgatu and Amtmannstíg, but this never materialized. The history of this street is a testament to both architectural innovation and evolving urban development, capturing a unique snapshot of Reykjavík’s past.

Bergshús – Skólavörðustígur 10

Skólavörðustígur has changed a lot in the last 30 years. Many old houses have disappeared and others built in their place. Bergshús is one of those houses. Constructed around 1865 by Alexíus Árnason, a police officer, this house is most famously known as Bergshús. The name “Bergshús” stems from Bergur Þorleifsson, a saddler who owned the residence for nearly fifty years, starting in 1885. Þórbergur Þórðarson, who was a tenant during Bergur’s tenure, wrote about his stay in his book “Ofvitinn.”

He describes his quarters in the attic at the west end of the house, comparing its ambiance to a traditional country living room, humorously referred to as the “Living Room” (Baðstofa) because it was under a sloping ceiling. By 1960, the building ceased to serve as a home, and its structure underwent significant modifications to accommodate a shop. Sadly, despite plans to relocate it to Árbæjarsafn in 1989, the building was demolished, and the move never transpired.

Mokkakaffi

Located on Skólavörðustígur in Reykjavík, Mokkakaffi stands as a testament to timeless café culture. Established on May 24, 1958, by Guðmundur Baldvinsson and Guðný Guðjónsdóttir, it remains one of Reykjavík’s oldest cafes. Today, Guðný continues to run the establishment. At the same time, Guðmundur, who had developed a passion for Italian cafe culture during his studies in Italy, passed away on November 9, 2006. Notably, Mokkakaffi was the first in the country to use an imported espresso machine. Beyond serving beverages, the café also hosts art exhibitions.

Tobba’s Cottage

Where Eymundsson bookstore now stands on Skólavörðustígur used to be the home of Þorbjörg “Tobba” Sveinsdóttir, a renowned midwife. This plot saw its first house in 1858, which Tobba acquired shortly after its erection. By 1898, she decided to replace it with a two-story wooden structure, residing there until her passing in 1903. However, the subsequent decades witnessed the house’s demolition, making way for the contemporary building in 1968.

Tobba’s dedication to her craft took her to Copenhagen’s maternity hospital, where she pursued the sole one-year midwifery program available to Icelandic women, completing it in 1856. She dedicatedly served in her profession until her retirement at 66, a mere year before her demise.

Among the myriad births she presided over, one notably resonates. In a humble abode at Laugavegur 32, she welcomed a boy named Halldór Guðjónsson into the world. This boy, under the pen name Laxness, would later achieve literary stardom, securing the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Beyond her professional contributions, Tobba was instrumental in shaping Iceland’s social fabric. She was a cornerstone in establishing the Icelandic Women’s Association in 1894, marking Iceland’s first association to embed women’s rights in its core tenets.

One of her last deliveries was that of a baby boy in a little house at Laugavegur 32. The boy, Halldór Guðjónsson, would later take up the pen name Laxness and ultimately win the Nobel Prize for literature.

Tobba was one of the founders of the Icelandic Women’s Association in 1894. It was the first women’s association in Iceland to include women’s rights in its manifesto.

Museum of Einar Jónsson

Step into history at the Museum of Einar Jónsson, where the building and artwork are closely linked. Einar Jónsson didn’t just create the art; he also designed the museum. While the building plans were officially signed by master builder Einar Erlendsson in 1916, the vision behind it was entirely Jónsson’s.

The museum opened on June 24, 1923, on Midsummer’s Day. Iceland’s first dedicated art museum was a landmark in the country’s cultural history.

The location is also significant. Einar Jónsson chose Skólavörðuhæð Hill, which was on the outskirts of Reykjavík at the time. His museum was the first building on the hill, offering panoramic views of the city.

Beautiful Sculpture Park Hidden Behind the House

Inside the towering heart of the museum, where Einar and his wife, Anna Jörgensen, once lived, you can enjoy a killer view of Reykjavík. Peek into their lives in the tower apartment, part of the museum that’s like a time capsule. It’s decked out in rare furniture and art from their era, making you feel like you’ve time-traveled!

Step outside, and you’re in Einar’s world of bronze – a sculpture garden with 26 casts of his statues. Some were so beloved they initially sat indoors before joining newer models in the fresh air. And here’s a fun tidbit: while living in the museum, Einar and Anna transformed its surroundings into a green haven. Rumor has it Einar himself planted every tree and shrub, including some age-old trees that still stand tall. This open-air gallery opened its gates on June 8, 1984. By then, it was already a buzzing site with many hands making light (and delightful) work!

The Acropolis of Icelandic Culture: Reykjavik’s Grand Vision

In 1904, Icelanders achieved home rule; by 1918, they had secured independence. Liberated from the Danish monarchy’s financial grasp, the newfound freedom was both exhilarating and challenging. While the nation no longer needed to appease foreign rulers, it had to manage with less financial support.

During the mid-1920s, when the Western world was prospering, one of Iceland’s most visionary projects was conceived: the Acropolis of Culture at the top of Skólavörðuholt. This was a period of affluence and indulgence, a bubble that, as history shows, would eventually burst.

The Vision of Iceland’s First State Architect

At the heart of this grand vision was Guðjón Samúelsson, state architect. Tasked with designing the hilltop, then the pinnacle of Reykjavik, he had initially sketched his ideas for public edifices on the hill back in 1916. By 1924, his vision was fully realized. Visitors ascending Skólavörðustígur would be greeted by an archway leading them to a vast square. Dominating this space would be a majestic equilateral cruciform church crafted in the classical style, harmonizing with the surrounding buildings. Flanking the archway would be residential structures, while behind the church, university student housing was imagined. Guðjón also conceived a “museum house” in the top right corner, intended to be the home for prominent Icelandic Museums: the National Gallery, the National Museum, and the Museum of Natural History. In place of this museum, a kindergarten now stands.

Comprehensive architectural plans for Reykjavik had been ratified by 1927. Many elements echoed Guðjón’s original concepts, including the proposal to construct the Reykjavik City Hall on The Pond’s northern side. This project would only come to fruition in the early 1990s.

However, like many grand dreams, the Acropolis of Icelandic Culture didn’t fully materialize. Today, remnants of this ambitious vision remain. Instead of the proposed cruciform church, the iconic Hallgrímskirkja stands tall. The Museum of Einar Jónsson was erected in 1924, and the area is dotted with educational institutions for all ages, except a university. However, this might change in the coming years as the University of the Arts is working on moving into the area!

Hallgrímskirkja: The Towering Beacon of Reykjavík

As you wander the streets of Reykjavík, the majestic silhouette of Hallgrímskirkja is a sight that continually draws attention.

Designed by architect Guðjón Samúelsson, the church’s facade is reminiscent of Iceland’s rugged landscapes. Its form mimics the basalt columns found across the island, capturing nature’s beauty in a man-made structure. Beyond its architectural allure, a visit inside offers a unique experience. Many find themselves taking the elevator to the tower’s peak, where panoramic views of Reykjavík await. The colorful rooftops, the harbor, and on clear days, the distant vistas of mountains and sea, paint a picture that stays with visitors long after they’ve departed.

Hallgrímskirkja is more than just a great viewpoint. It’s a key part of Reykjavík’s cultural life. The church hosts organ concerts and various ceremonies, making it a central part of the city’s events.