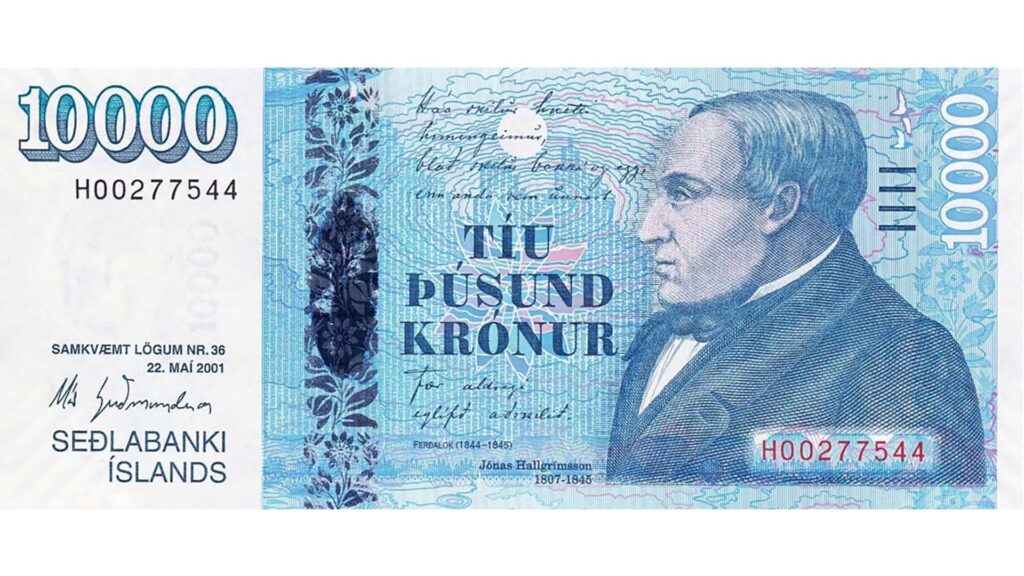

November 16 every year is the Day of the Icelandic Language. The day is special for Icelanders as it is the birthday of Icelandic poet, naturalist, and author Jónas Hallgrímsson. He was one of the founders of Fjölnir in Copenhagen in 1835. It was an Icelandic magazine that influential Icelandic men living in Copenhagen used to promote Icelandic nationalism in hopes of motivating people to fight for Iceland’s independence. A few years back, he got the honour of adorning our newest banknote, the 10000kr bill. What makes him so important to Icelanders is that he created hundreds of words which we still use today.

Obviously, most Icelanders are proud of their language. We speak a language that has been mostly unchanged for over a thousand years. That means we can read the old Icelandic sagas in their original writing without trouble. Sure, there is a word here and there that possibly has disappeared from the language, but most of the text is legible.

A Very Short History of Iceland

To make the long history of Iceland short, settlers came to Iceland in the 8th century. In 1262, Icelanders went under Norwegian rule again. This happened after the prosperous Icelandic commonwealth ended in a civil war. However, the transition was relatively peaceful. Icelanders just signed a contract.

However, in 1380, Norway (and thus Iceland) became a part of the Kalmar Union with Sweden and Denmark, where Denmark was the dominant power. This created a severe power imbalance for Iceland as, unlike Norway, Denmark did not need Iceland’s wool and fish.

So, Icelanders went under Danish rule. Icelanders weren’t all that happy about this new turn of events, as they didn’t choose this like the union with Norway. Iceland remained under Danish rule in one way or another until 1944. Iceland got home rule in 1904, got sovereignty in 1918, and finally became a republic in 1944.

By the 19th century, Icelandic and Danish were used mostly interchangeably by Icelanders. While Icelanders spoke Icelandic, it was heavily influenced by Danish.

Rasmus Rask Comes to Iceland

In the early 19th century, a Danish man called Rasmus Rask (1787-1832) came to Iceland. He was a great linguist and had dreamt of coming to Iceland all his life. Finally, in 1813, he came, spent two years and became fluent in the language.

He is considered the founder of comparative linguistics. Older linguists had drawn conclusions about the relatedness of languages based on individual words that looked similar. Rask pointed out that these are often loan words from other languages and therefore say nothing about the origin of the language. Instead, he compared grammatical analogies and, for example, demonstrated the Germanic a-mutation.

Rask became convinced that Danish influence in Icelandic should be stopped and that it was essential to strengthen Icelandic culture. When he arrived back in Copenhagen, he established Hið íslenska bókmenntafélag (The Icelandic Literary Society), which still exists. Rask was its first president.

Jónas Hallgrímsson, Shakespeare of Iceland

Jónas (1807-1845) could be called Iceland’s Shakespeare. He’s one of the founding fathers of Romanticism in Iceland and introduced pentameter to Icelandic poetry.

Moreover, he, like Shakespeare in England, created a plethora of words still being used today.

Jónas was born in Eyjafjörður in North Iceland. He was bright and won a grant to study in the School at Bessastaðir (the current residence of the President of Iceland) after having attended school for two years in North Iceland.

When he finished his six years at Bessastaðir, he moved to Reykjavik, where he got a job as the sheriff’s clerk. During that time, he also worked as a defense lawyer. In 1832, he sailed to Denmark to study law at the University of Copenhagen.

After four years of study, he switched to literature and natural sciences. During his time at the university, he established the magazine Fjölnir with his fellow Icelandic students Brynjólfur Pétursson, Konráð Gíslason, and Tómas Sæmundsson.

When he graduated, he was awarded a grant from the state treasury to conduct scientific research in Iceland, which he worked on between 1839 and 1842. For the remainder of his life, he split his time between Copenhagen, research trips to Iceland, and writing for Fjölnir. The magazine is where many of his poems and essays first appeared.

On May 21, 1845, Jónas slipped on the stairs to his room in Copenhagen and broke his leg. He went to the hospital the next day but died of blood poisoning, aged only 37.

Words by Jónas

Since Jónas was a naturalist and conducted scientific research and translated scientific texts, many of his words relate to that.

- Aðdráttarafl: Gravity. Made from að-dráttar-afl. Literally means to-pull-power.

- Gangverk: clockwork, drive mechanism. Gang-verk, means running work.

- Efnafræði: Chemistry. Efna-fræði, Chemical-studies.

- Lambasteik: Lamb roast. Lamba-steik, means lamb roast.

- Tunglmyrkvi: a lunar eclipse. Tungl-myrkvi, means moon-darkness.

- Spendýr: Mammal. Spen-dýr, means tit-animal.

- Mörgæs: Penguin. Mör-gæs, means fat-goose.

- Sólkerfi: solar system. Sól-kerfi, means sun-system.

- Sporbaugur: an ellipse. Spor-baugur, means trail-ring.

- Undirgöng: tunnel. Undir-göng, means below-tunnel.

He created dozens and dozens of other words, and the subject is enough for a whole book.

Special Icelandic words

While Jónas was a master wordsmith and important to Icelandic culture, he didn’t, of course, create all the words.

There are quite a few Icelandic words you cannot find a single word for in other languages, like gluggaveður and sólarfrí (window weather and sun vacation). Like in every language, some words can have a similar meaning between languages, but there’s a certain cultural feeling connected to it, which doesn’t translate well. One of those words is the Danish word hygge or the Icelandic verb “að nenna.”

Að nenna

Að nenna is challenging to translate, as it is also connected to a feeling. Ég nenni þessu ekki means you cannot be bothered to do something, but the sense is deeper. You may want to do it, even have a longing to do it, and even a will, but you just cannot be bothered. You can also ask: nennir þú að gera þetta fyrir mig? Which would translate to can you do this for me. But as the verb is not “getur” (can) but “nenna,” it makes a more complicated question. It is often used when asking someone to do something boring, like taking out the trash or washing the dishes.

What makes it even more complicated is that you sometimes do the thing, even if you cannot be bothered. You can take out the trash, even if you don’t “nenna” it. The best way of describing it is maybe that you can’t get yourself to do it. This word can be found in other Nordic languages, though.

Skriðdreki

Like German, Icelandic uses compound words, and many of our best words are made that way. One such word is for a (military) tank. Skriðdreki.

The word was created during the First World War and was first used in a newspaper in 1917. The word literally means crawling dragon. Initially, people used the word “tankur,” derived from the English word tank. Still, obviously, people didn’t like it enough, so a new word was created. Icelandic already had a word called “bryndreki” (armor dragon), a translation of the Danish word panserskip and used for certain navy ships. At first, people used “bryndreki” and “tank/tankur.” Still, people wanted an Icelandic word and thought the older bryndreki could be confusing.

Tölva

One of the reasons why Icelandic is still a living language, according to those in the know, is that we still create new Icelandic words when something new arrives. Even if we use “Facebook,” we have an Icelandic word that is also used a lot, fésbók. It literally means Facebook, so it’s handy. It is not a given that a new Icelandic word is used instead of the foreign one. Pizza, for example, has the Icelandic equivalent, flatbaka (flat bake). Still, most people use pizza, even if flatbaka is used. In regards to Twitter, many people use “að tísta” for “to tweet” – a literal translation, although the loan verb “að tvíta” (tweet-a) is also used.

However, one of the most successful technological words is the word for computers: tölva. Most countries use some variation of computer, but Icelanders decided to create their own word for it.

Tölva was created from two words: völva and tala – prophetess and number, number prophetess. How brilliant is that?

The University of Iceland got its first computer in 1964, IBM 1620, and they felt they needed a word for the machine. One of Iceland’s foremost Icelandic linguists at the time, Sigurður Nordal, had the honor of creating this great word.

Kviðmágur and samlóka

In a completely different direction is the word kviðmágur. It translates as stomach brother-in-law and refers to two men who have slept with the same woman.

This is a relatively new word in the language. The oldest instance of it in a newspaper is in 1951. It might have been used colloquially before that. Oddly, there isn’t a female equivalent for this word, although kviðsystir (stomach sister) has sometimes been used. There is an old word, “elja,” meaning mistress or a woman who competes with another woman for a man’s love. However, the term has lost that meaning and is only used for diligence and perseverance today.

Others have begun using the word samlókur, derived from samloka (sandwich) and is translated as fellow-penis.

Líkamsvirðing

This is a good word. It is a translation of “body positivity” and translates as body respect. There’s not much more to say about this word; it implies all there is. This word is new and was first printed in a newspaper in 2007.

Smitskömm

This is the youngest word on our list, as it was coined during the Covid-19 pandemic. It translates as “infect-shame.” It relates to the shame people felt if they suspected they might have accidentally infected loads of people with Covid.

Frekja / frekur

This word is often used to describe small children who are demanding and take hissy fits. It can also describe a grown-up person – usually a woman – who is demanding. In that meaning, it is obviously derogatory.

The difference between frekja and frekur is minimal, apart from being nouns and adjectives, respectively. A person who is “frekur” is demanding, pushy, and even greedy. Possibly entitled. This can be a one-time thing or in certain situations. However, if someone is “frekja,” it is a part of their personality.

Protecting the language

As there are under 400.000 people who speak Icelandic, it is perpetually on the verge of being wiped out. Various measures have been taken to protect the language, but many believe more is needed, especially with the Internet. Young people often hear English more than Icelandic, and it is far easier to reach films and tv shows in English than in Icelandic.

In 1964 the Icelandic Government established the Icelandic language committee. The committee’s role is to advise the government on the issue of the Icelandic language on a theoretical basis and to make proposals to the minister on language policy, as well as make annual resolutions on the status of the Icelandic language. The committee can initiate suggestions about what is done well and what can be improved in treating the Icelandic language in the public arena. It also draws up Icelandic writing rules that apply in schools, for example, and how Icelandic should be taught. Fundamental changes to writing rules are subject to the approval of the minister.

In the beginning, one of the biggest changes the committee suggested was abolishing Z from the Icelandic language. It was approved because it had no particular sound in the language and was pronounced the same way as S.

The newest language policy was approved in 2021 and is valid until 2030.

The Icelandic Name Committee

Another way the government has chosen to protect the Icelandic language and culture was by establishing the Icelandic Names Committee in 1991. People have criticized it since its foundation because if you want to give your child a name that has not been used before, it has to go before the committee.

They have a reputation for being unreasonably strict. Still, one of their goals is to only allow names that can be conjugated and follow Icelandic grammatical rules. People have regularly fought them; sometimes they’ve won and sometimes lost. One such case was of a girl called Blær. It is traditionally a male name, but her grandmother was also called Blær. But since no one had had that name before the committee was founded, they refused to allow it.

Usually, they allow it if there is a historical use of the name, but for some reason, they refused to allow it. In the end, after many years, they finally gave their permission.

Cases such as these, where a female child cannot have a male name, have become absolute with new laws on freedom of sexual self-determination. One of the things it allowed was for people to choose whatever name they wanted, regardless of gender.

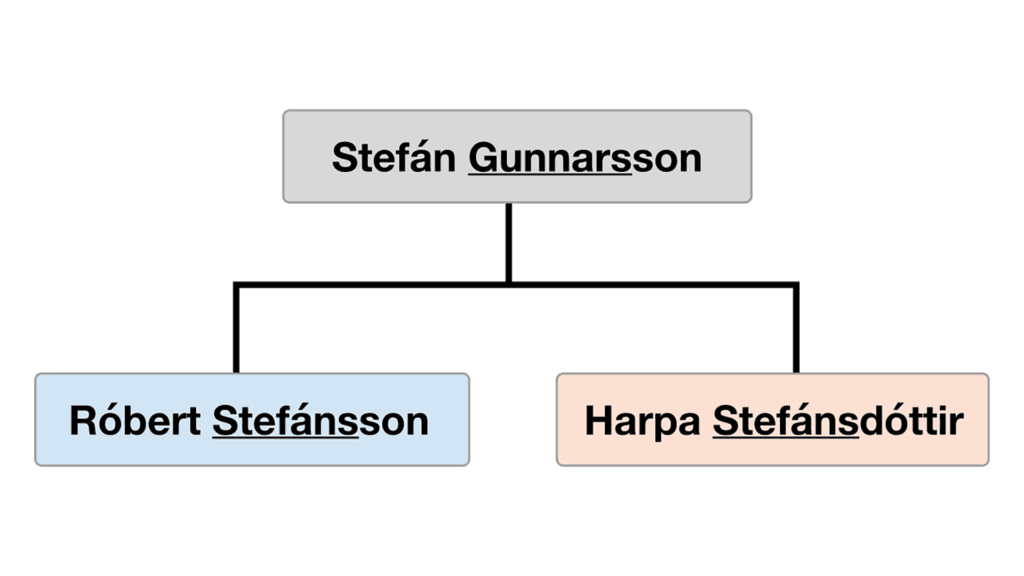

Patronyms, matronyms and family names

One other name law which has yet to change, though, is that you can only take up a family name if it has already been in your family. That is to protect the patronymic surname system in Iceland. However, today you can also take up the name of your mother or both parents.

For those who do not know, it means that most people in Iceland have their first (and second name) and then are called son or daughter by their father. So if we have Jón Sigurðsson, he’s Jón, the son of Sigurður.

For non-binary people, it has been suggested to use the word “bur” instead of son and dóttir. Bur technically means “son,” but as it is of the same word stem as barn (child), it can well be used. This has not been accepted yet, so who knows what will happen.

The Name Committee has become more welcoming of new names, and recently it allowed the names Nieljohníus, Villiblóm, and Paradís. The latter two are Wildflower and Paradise.

The most commonly given names in 2021 were Aron and Embla. For all living Icelanders, the most common names for women are Anna and Guðrún. For men it’s Jón, Sigurður and Guðmundur.

Please signup HERE for our newsletter for more fun facts and information about Iceland!